When I ask Rawi Hage how he chooses the decisive moment in his stories, which often brilliantly and unexpectedly switch course, he tells me that his instinct comes from his training as a photographer, and the years he lived through the civil war in Lebanon. “Because I lived through the war,” he explains, “there was always this parallel between a bullet and a photograph – one is leaving, the other is capturing; there’s always that decisive moment.” The concept of the “decisive moment” is Henri Cartier-Bresson’s: the precise instant that reveals the larger truth of a situation.

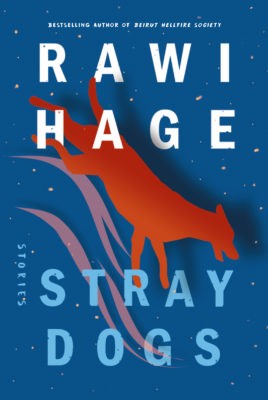

Photography, both in theory and practice, is a prominent organizing principle of Hage’s new collection of stories, Stray Dogs. Having already published four acclaimed novels, most recently Carnival and Beirut Hellfire Society, Hage has returned to short fiction, where his writing practice originated. We spoke over Zoom in the sudden mid-May heat, about photography, exile, failure, and the short story form.

Stray Dogs Knopf Canada

Rawi Hage

$29.95

cloth

216pp

9780735273627

In “The Wave,” the Lebanese protagonist, an ex-academic living in Montreal, is increasingly in conflict with his white Québécoise wife, who, while visiting Lebanon together, romanticizes the villagers in the mountains before accusing her husband of being “a Third World Elite.” He, increasingly obsessed with mathematically predicting natural disasters, is certain that a tsunami is imminent, but, in a moment of miscalculation, loses his wife to other, more unpredictable forces. In the titular story, Samir, whose Jordanian family is alarmed at his decision to study photography rather than business, in the United States, is jolted back into the space of home and grief upon receiving news of his father’s death while presenting at a conference in Tokyo. He realizes that his family won’t delay his father’s burial so that he can travel back to Jordan: “The ancient Arabs had never waited. They moved through the dunes and under the heat of the sun, leaving behind what couldn’t be carried on their animals’ backs.”

These stories are not, on their surface, autobiographical – they feature a wide array of protagonists, in Beirut, Baghdad, Montreal, Berlin, Tokyo, Warsaw, and elsewhere, from the 1970s through the twenty-first century, and sometimes out of time entirely. However, Hage tells me that “in a bizarre way, it’s an autobiographical book” – not because it directly describes his own experiences, but because it is filtered through the lens of photography, a medium that Hage has worked in and kept close to throughout his life.

He describes his early years in Montreal after leaving Beirut, “trying to survive as a newly arrived immigrant,” studying photography at Concordia before doing a Master of Fine Arts at UQAM, while driving a taxi to make a living. Photography was his first love, and yet he moved towards writing when he realized that photography was undergoing major changes, both technologically and philosophically, that he couldn’t adjust to. With the 1990s came a wave of capitalist outsourcing, which led to the decline of the artist’s proximity to the worker, he says, and this made photography less compelling to him. There’s a word in Arabic, he tells me, that describes people who experience two distinct eras: مُخَضْرَم (mukhadram). He tells me this in reference to the overlapping eras in photography, but the term could encapsulate the characters in Stray Dogs, too – they repeatedly endure the “almost fatal existence,” in Hage’s words, of living “in between culture, in between affiliations.”

Hage finds that “photography makes a great literary subject because it’s so versatile, it covers the whole spectrum: from nation states spying on people, to wedding photography, to everything in between.” The characters in these stories are often changed indelibly by photography, or by a single photograph or image: in “The Whistle,” the protagonist contends with his youth during the war in Lebanon, when he forced his cousin to drive around Beirut with him, attempting to photograph falling bombs; in “The Fate of the Son of the Man on the Horse,” a struggling photographer in Montreal has his life upended by a visit from Sophia Loren, bearing a photograph and clues about his family’s history in Italy; in “The Duplicates,” an obsessive photographic archivist sees his own death predicted in the mysteriously altered prints of an eighteenth-century manuscript. Photography is “a very seductive medium,” Hage says. “If there’s any commonality in all these stories, it is about failure, about people who fail, and who are deceived by the medium of photography.”

Failure, coupled with the uncertain state of being in between eras, or between national, class, and political identities, characterizes the situations of many of Stray Dogs’ protagonists. The opening story, “The Iconoclast,” is a spare, trenchant portrayal of these tensions. Hage describes it as being “about a man who knows the West well, is a product of the East, and is being rejected by both sides.” This hybridity is dislocating and sometimes painful. A man at a party thrown by the narrator’s artist neighbours in Berlin accuses him of being a “developing-world, privileged [sort]” who is “either naïve or […] complicit with neoliberal capitalism masquerading as a cultural contribution to the world.” Later, in a militia-controlled neighbourhood in Beirut, a neighbourhood that the middle-class narrator usually avoids, a woman tells him to “go back to [his] beautiful neighbourhood,” asking, “what are you people always so afraid of?”

“The fate of hybridity is to deal with perpetually explaining yourself,” Hage says. Being part of what he reluctantly terms the “cosmopolitan strata” often means that “your discourse is against the West, while also in some way repulsed by your own Third World Elite; and you are contributing to discourse, or you are able to contribute because the West is allowing you to speak, and also you are speaking on behalf of a proletariat from your own country that you don’t really belong to.”

The protagonists in Stray Dogs may struggle to speak, may become seduced by the false promise of a photograph, may fail to find home again, but they are vividly present in these texts, in their confusion and pain and hybridity, a multi-voiced testament to carrying on. In “The Whistle,” the narrator tells his cousin in Beirut that miracles do not exist. His cousin replies that they do, “and the proof is that we are here and alive, in spite of people’s stupidity and the terror we endured.”

This summer, for a change of pace, Hage is taking on a different sort of project: “I’m learning how to garden,” he tells me, chuckling a little. “Yeah, my biggest challenge right now is how to plant tomatoes.”mRb

Excellent commentary on this clearly written book of startlingly ‘exposed’ characters (or their images, at least…)

Thank you!