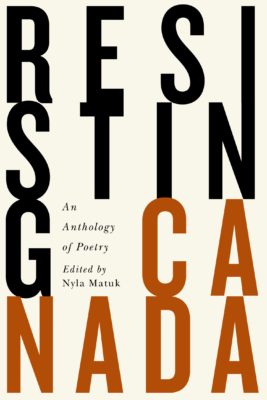

Resisting Canada: An Anthology of Poetry, edited by Nyla Matuk and published by Véhicule Press, slices through the narrative of Canadian exceptionalism, the idealized notion of that elusive “melting pot” we’ve all heard so much about but have yet to experience for ourselves. It is a searing critique of a settler state that continues to silence, abuse, and oppress Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, and features the work of new and established figures in contemporary poetry: Lee Maracle, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Canisia Lubrin, and Billy-Ray Belcourt, among many others.

A poetry anthology of this scale tackling Canada’s hypocrisy is long overdue. I find myself wondering if this country has ever reflected on its violence. Of course, reflection implies a past. That is not the case in Canada, where, as Matuk states in her introduction, “colonization isn’t merely a historic phenomenon we can dismiss as irreversible. It’s an ongoing set of practices negatively affecting human beings and the environment.” Having to answer for its continuous crimes is something that the settler state of Canada refuses to do. Perhaps because it goes against the “continued maintenance of national fairy tales,”1 (to use Alicia Elliott’s phrase) that we’ve been indoctrinated with, or perhaps because the magnitude of the crimes leaves us speechless. Marilyn Dumont’s “Our Prince,” with its chillingly blunt ending, affirms our complicity and forces us to think of Canada’s silence:

and when their children ask

what Louis did

they will have to answer

Canada has not answered. I had a chance to speak with Matuk this past September on the topic. “The accountability factor, and the truth and reconciliation, just to use that term – which of course is an official term – but to use it in

the sense of small t truth, small r reconciliation. The operationalization of that hasn’t really taken hold, which we saw most recently when the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was published in June. All the reactivity to that in the mainstream media, the defensiveness at labelling that a genocide… all of that is denial, and that is a feature of settler-colonial states.”

Resisting Canada

An Anthology of Poetry

Edited by Nyla Matuk

Signal Editions

$22.95

paper

280pp

9781550655339

What do those atrocities look like? We bear witness to them vividly throughout this anthology: residential schools, internment camps, torture, government-sanctioned genocide. These are the wounds left untreated, their effects felt not just in the body and soul, but on societies themselves. “It’s not just psychological trauma… the colonization itself, it creates more pragmatic setbacks too,” Matuk says. “[It’s] the de-development of cultural and civic identities, cities, and natural environments.”

Throughout Resisting Canada, there is a widening of time – a vision of life before, during, and after this current colonization. It’s breathtaking how much more history the scope of the peoples and lands around us contain when we think of them outside of our typical colonial lens. As Matuk puts it, “You are a chapter of this, you are the colonizer at the moment, you were the colonizer 200 years ago and 300 years ago… but the Indigenous Peoples have always been here.”

I apologize for not coming sooner, to free your eyes,

to re-craft the images below,

to raise my voice in resistance

to the desecration of your eternity

(“Streets,” Lee Maracle)

And once we are made aware of this eternity, we begin the process of decolonizing our relationship to the world around us. As Anishi- naabe artist Susan Blight says, “it is not about our knowledge fitting into yours – decolonization is about how you fit into us.”

Also relating to time are lineages of pain, the lingering presence of traumas from this generation and past generations. In Michael Prior’s poignant narrative poem “Tashme,” Prior and his grandfather take a road trip through British Columbia to visit the former internment camps where Japanese-Canadians were imprisoned after Canada declared war on Japan. The spectre of the past remains felt in the present with this flowing, mesmerizing poem. In Rosanna Deerchild’s jaw-dropping “mama’s testament: truth and reconciliation,” she records her mother’s experiences in a residential school. It’s a poem so raw and piercing as to illicit goosebumps:

ever since that white guy

nete in ottawa said he was sorryas if

he knows anything about those placeshe wasn’t there

he doesn’t knowhe wasn’t there

when i needed comfort

when i cried

It’s “history from below,” a method of showcasing narratives that Matuk’s selection of work in this anthology employs in many different formats, here highlighted by the archiving of oral histories. The intergenerational trauma the Canadian state has fostered, and the process of naming the pain of parents, grandparents, ancestors – it’s a carrying forward of stories to a new generation, who shares those stories that may not always be able to be shared by their direct survivors.

***

My own family lineage is one borne of resistance; my parents fought against the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile’s 1973 coup and were exiled. There, in the 1950s and ’60s, la nueva canción (new song) movement was integral in the expression of solidarity during repression. During the dictatorship, traditional Andean instruments were banned, and many of those artists – most famously Victor Jara – were among the first to be tortured and killed. Matuk, who is of Palestinian descent, is herself hypersensitive to the power of poetry, of the danger it presents to the ruling class. The book is dedicated to Dareen Tatour, who was “arrested during an Israeli police raid in October 2015, a few days after posting on Facebook and YouTube a video of herself reading a poem titled ‘Resist, my people resist them’ as the soundtrack to images of Palestinians in violent confrontations with Israeli troops.”2 The empathy that poetry fosters in the public is not to be taken lightly. Matuk says, “They are considered dangerous; they are going against, they are challenging, and refuting the ideology of the neoliberal state, they are resisting imperialism, they’re calling for decolonization and revolution, really.” During our interview, Matuk brought up William Carlos Williams’s lines:

My heart rouses

……………….thinking to bring you news

………………………………..of somethingthat concerns you

…………………and concerns many men. Look at

……………………………………..what passes for the new.You will not find it there but in

.………………..despised poems.

……………………………………It is difficultto get the news from poems

………………..yet men die miserably every day

………………………………….for lackof what is found there.

Resistance poetry then, with its urgency and re-contextualization, becomes timeless and necessary for the soul, not soon to be washed away in the deluge of daily broadcasts.

Anthologizing creates legacy. It’s haunting to think of the lives lost to white supremacy and colonialism, to think of the people, the ways of life, the art ripped from this world, “cut short or ruined,” as Matuk says. Resisting Canada is an urgent appeal for us to join those who are on the frontlines of revolution and eschew the idea that defying the status quo is not our job, or is messy, or is not civilized. As Matuk mentions, “Civility is what shuts people up, tells them that they can’t be enraged at what has been done to them.” We must shift our view of what defiance means: Defiance is powerful, defiance is necessary, defiance is the hope in Indigenous futures, in Black futures, in futures free of colonization. It’s that hope these poems leave you with.

Things change, slowly

Sometimes overnight

But never do they not

(“Alotta Hullabaloo,” Janet Rogers)

This article was written on the unceded Indigenous lands of Tiohtiá:ke, for which the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is the custodian of both the land and water. mRb

0 Comments