A book about friendship, polyamory, queerness, and unconventional families, Run J Run has all the makings of an exciting novel. But, bogged down by racial and mental health tropes, the book leaves an unsettling feeling.

The book begins with J and Zak, two best friends in their mid- thirties. Following Zak on his bike, J says, “Zak grinned at me over his shoulder, then proceeded to accelerate his death-defying weaves through traffic. […] After his third suicidal maneuver, I was tempted to ditch him. But if I did that, who would watch his back?” This foreshadowing offers insight into the dynamic between these two characters. The narrative follows J and Zak as they start dating while Zak is also in a polyamorous relationship with Annie. When Zak’s mental health declines, J moves in with Zak, Annie, and their two kids, and Run J Run depicts this unconventional family as they try to support Zak through his depression and suicide attempts.

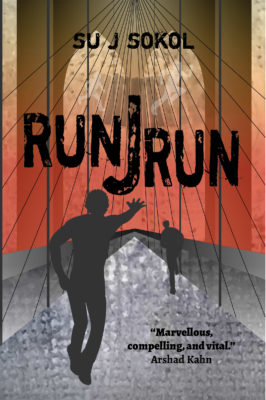

Run J Run

Su J. Sokol

Renaissance Press

$20.00

paper

296pp

9781987963519

On the other hand, Run J Run’s urgent tone emulates the experiences of living with a loved one who is suicidal. Exploring the fatiguing nature of care work and the fallibility of care workers, the novel examines the difficulty of setting boundaries. For instance, Annie, Zak’s partner, tells J that she’s happy he’s moved in, for selfish reasons: “You still don’t get it, do you? That’s why you’re living with us. I had it all worked out. You’d take care of Zak so I could take care of the kids. I manipulated you.” Despite Annie’s claim that she manipulated J, who moved in with them of his own volition, it is understood that the intimate partners of people who are suicidal often take on a lot while trying to support their partners.

Police violence and racism are also touched upon thematically. Despite the effort to portray the seriousness of racial violence today, the anti-Black racism in the book feels like a plot point, rather than a nuanced portrayal that speaks to the experiences of many Black people in Canada and the United States. Dez, Zak’s student and a young boy who is killed by the police, is a two- dimensional character used to further the plot. Ultimately, his death becomes more about Zak, another trigger and stressor in his life. When Zak makes a speech about Dez at the end of the school year, all he says is: “Let me take a few minutes to talk about your classmate Dez …” and the rest of the speech is never shared with the reader, making Dez’s life seem insignificant to the novel. The child is left dead and storyless, his limited story not honouring the integrity of Black life.

Run J Run was compelling and easy to read, and yet I couldn’t help wondering whether the narrative was gripping or whether I was just frightened for the fate of the characters, the narrative teetering on the edge of trauma porn. What are our responsibilities when writing about mental illness and race? What are our responsibilities when writing outside our experiences to the real people living these experiences? This responsibility cannot be taken lightly. mRb

0 Comments