North American public discourse is saturated with lies. A vast network of online conspiracy theorists and far-right propagandists has taken root on internet message boards and social media platforms. Broadcasting malicious falsifications to devoted audiences, conspiracy theorists resist scrutiny even as every statement they make is divorced from empirical reality.

The “alternative facts” they spread exert a strange kind of gravity on contemporary life. Taken as a whole, they create a worldview in which their believers’ most lurid fears come vividly alive. Audiences are made to believe that they are locked in a war against an emergent new world order, which, once in power, will suppress their freedoms and control their minds. Through this cracked mirror, all school shootings are staged “false flag” operations, political activists are paid operatives, and the weather is controlled by the government. Rooted in racism, xenophobia, misogyny, and isolationism, conspiracy evangelists make their followers reliant on them by insisting that all other media is either lying or complicit.

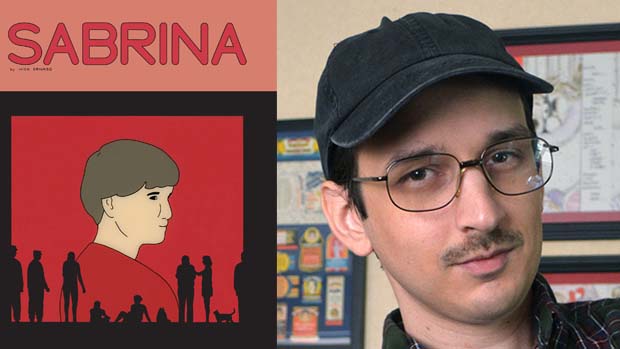

Sabrina

Nick Drnaso

Drawn & Quarterly

$32.95

cloth

204pp

9781770463165

Sabrina begins with a short glimpse into its title character’s life. Sabrina Gallo is a young middle-class white woman cat-sitting at her parents’ home in Chicago. In these early pages, Drnaso’s small panels lavish attention on the details of domestic space. The glass lampshade hanging over the dining room table, the kitchen cupboards, and the wallpaper in Sabrina’s childhood bedroom are all lovingly rendered in Drnaso’s clear line. As these details accrue, we’re drawn into a world of quotidian normalcy. The characters, however, are sparely rendered, each face consisting of minimal lines and round dark eyes.

From that moment of calm, the novel leaps a month forward and a thousand miles west. At the Colorado Springs train station, Sabrina’s boyfriend Teddy is picked up by his childhood friend Calvin. The men are uncomfortable around each other, Teddy saying little and Calvin rambling awkwardly. Sabrina is told entirely in scene, without narration to clarify what is happening. The tension rises as these two men reconnect. Teddy is haunted. Something has driven him west, but what?

Calvin drops Teddy off at his half-empty house before leaving for work. An Air Force “boundary technician,” Calvin works nights at a military server farm. Speaking to his commanding officer, he relates that Teddy is struggling after Sabrina’s sudden disappearance. “It’s one of those horror stories you hear about,” Calvin explains. “She just never came home. They even got her on a security camera […] walking home from work at her usual time, and after that, nothing.”

Sabrina’s disappearance haunts the novel, the mystery of her absence outlining its shape. As the days drag on, Teddy becomes ever-more despondent, withdrawing from life completely. Emotionally detached Calvin, reeling from a recent separation from his wife, provides takeout dinners for Teddy and tends to him during his night terrors. But he cannot ease his friend’s trauma.

The muted colour scheme of Calvin’s condo and the tightly closed window blinds epitomize the book’s feeling of emptiness. It is as if these two near-strangers are sharing an anonymous hotel room rather than a home. This is echoed by the vacant nocturnal scenes Calvin passes through on his way to and from work. The book’s hollowed-out emotional landscape is populated by functional, low-rise architecture. This is a world of isolation, loneliness, and disconnection.

At his most emotionally vulnerable, Teddy is drawn into the paranoid world of conspiracy radio. Alone while Calvin is at work, he listens to broadcaster Albert Douglas, clearly a stand-in for Alex Jones, and comes to see the world through his dark lens. The radio host seems benign at first, pining for a simpler time in plain-spoken language. But it isn’t long before Douglas announces that a group of shadowy “orchestrators” are behind many of the problems facing contemporary America. Where previously Teddy vacillated between sorrow and emptiness, conspiracy radio stokes his rage. He lashes out at Calvin and, driven by Douglas’s paranoid visions, teeters on the brink of violence.

But when Sabrina’s sad fate is finally revealed, her story feeds into Douglas’s alternate reality. He insists on air that she is part of yet another “false flag” operation, unleashing his horde of listeners on Teddy, Calvin, and Sabrina’s family. Drnaso is an internet native who intuitively understands online culture. His dramatization of the pain suffered by these characters as they face an enraged mob is among the most searing portrayals of online cruelty yet written. Hidden behind screen names, these trolls launch a stream of death threats and crank theories into their targets’ inboxes. Drnaso shows us how his characters’ sense of the world is shaken as they are forced to reckon with this warped parallel dimension.

A taut psychological thriller, violence is everywhere and nowhere in Sabrina. We hear about young women being chased by frat boys during spring break. Calvin keeps guns to protect his property and accidentally leaves them out. News reports of mass shootings punctuate the book as part of the texture of everyday life. At one point Calvin gives up watching the news, telling a friend: “I just feel like ‘I don’t care how many people were shot today. I can’t take it.’” Violence is inescapable.

To his immense credit as a storyteller, Drnaso maintains this taut atmosphere without illustrating a single violent act. When a video of a monstrous crime emerges, Drnaso shows the shocked reactions of the people watching it on television, but leaves the screen itself blank. He employs a variety of techniques to convey terror while dodging graphic depictions, narrating it through office chit-chat about horrific news, search engine sidebars that casually report death and mayhem, and a television news voice-over reflecting on the troubled legacies of 9/11 while people are shown visiting the memorial museum. One drawback of Sabrina, however, is that the book is populated entirely by white characters and there is little acknowledgement of the unique ways that racialized, immigrant, and other minority communities are targeted in this atmosphere of hatred and violence.

Sabrina is the latest in a long line of graphic novels to receive attention from literary juries. When it was included on the Man Booker Prize longlist earlier this year, some commentators hailed it as a watershed moment for comics. Other more thoughtful critics recognized that literary comics have been awfully good for a long time, and have been embraced by so-called mainstream audiences – topping bestseller lists and winning major literary prizes – for decades now. With the Booker nod, Sabrina joins the ranks of politically powerful and stylistically innovative graphic literature that has crossed over into wider readership, including Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which won a “Special Citation” Pulitzer Prize in 1992, Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, which took the Guardian First Book Award in 2001, and Marjane Satrapi’s critically acclaimed Persepolis, which was made into a feature-length animated film codirected by the artist, winning a Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007.

With or without a major prize, Sabrina deserves to be read widely as an insightful and intimate portrait of the anomie of contemporary American life. Among the most ambitious books published by Drawn & Quarterly, the book is a testament to the Montreal publisher’s dedication to broadening the scope of the kinds of stories being told in the medium. For over a quarter-century, the press has worked doggedly to make space for cutting-edge work, and Sabrina is another worthy milestone. Formally and thematically innovative, it serves as a stunning indictment of the conspiracy culture that first metastasized online and the toxic ways it is seeping into the real world.

Drnaso’s masterful portrait of contemporary America is bleak. He portrays a hollowed-out social world, an emotional wasteland where human connections are more tenuous than ever before. The book nearly ends on a hopeful note, with characters showing signs of recovery. But in its final pages, Calvin has a dark nightmare in which a masked murderer holds a knife to his throat, indifferent to his pleas for mercy. This haunting image is Sabrina’s final message, a reminder that the American machinery of fear and violence grinds ever on. mRb

0 Comments