In the Jewish tradition, fragments of worn-out holy books are not discarded when they are past use; instead, they are buried in a cemetery or subterranean storage room. In these underground genizot, the name of God is protected from destruction. The holy fragments – sheymes – provide Elizabeth Wajnberg, a child of Holocaust survivors, with a powerful metaphor for the recollections she patches together in her memoir.

Wajnberg covers over fifty years of history, from her parents’ pre-war Poland to 1950s and 1960s Montreal to her own free-spirited years in Paris as a young adult to, ultimately, the failing health and final years of her mother and father in the 1990s. The author’s strongest moments come in that last phase as she describes the changes time brings to bear on relationships between parents and children. If seeing one’s parent placed in a nursing home and stripped of their autonomy is a nightmare for most, then for Holocaust survivors and their children this experience is a special kind of hell. Amid the trauma of watching a loved one lose independence, the process of institutionalization can also evoke memories of past traumas for both survivors and their children. “They say we can’t cope because we have no model for dying,” says Wajnberg’s friend, a fellow child of survivors. “Nobody we know has ever died a natural death.”

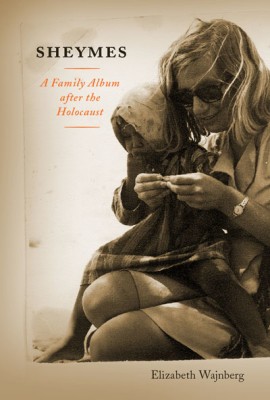

Sheymes

A Family Album after the Holocaust

Elizabeth Wajnberg

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$34.95

cloth

292pp

9780773544598

Sheymes exhibits an unfortunate tendency to belabour the point, turning some of the author’s sharp observations into blunt instruments of repetition. Recounting the three days and nights her young sister spent separated from their parents – on the other side of a barbed wire fence, awaiting a gas chamber-bound train that, fortunately, never came – Wajnberg writes that, inexplicably, the Nazi officers “gave her back, but my mother could no longer take her back.” A poignant sentence if there ever was one, but it’s deprived of its potency when repeated verbatim a page later in a manner that suggests not creative license but rather that the author had forgotten she’d said it already.

Leaping between periods of a memoirist’s life is a time-honoured tradition, but without a strong voice and writerly control, the narrative inevitably becomes sloppy. The haphazard dissemination of family history and chronology of events isn’t helped by the book’s muddied tenses. One moment Wajnberg is an adult in Switzerland in the 1980s, the next she’s a five-year-old traversing the ocean (and then back again); meanwhile, present, past, and past-perfect tenses attach themselves willy-nilly to anecdotes, causing the reader to frequently question which Wajnberg is at the helm. The 5-year-old? The 1980s Parisienne? Or the memoirist writing today? Memories read like bullet points, particularly in the first chapter, and the chapters, I would wager, were written in no particular order and arranged ex post facto.

The author’s dedication to conveying her parents’ non-standard Yiddish is commendable, as is the helpful and succinct introductory note explaining the considered approach to its transliteration; however, the reading experience would have been greatly aided by a glossary as many terms are either clumsily repeated in the English or passed over entirely with the apparent hope that the (usually insufficient) context will fill in the blanks.

Drawing on the annual retelling of the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, Wajnberg writes: “Unlike Passover, we cannot tell [the story of the Holocaust] in unison. The community is gone and so almost are the survivors. It has to be told singly, one by one. Each story is different and it is different each time it is told. Somehow my father’s body always stored up a detail to be revealed at some other time, in some other place.” Sage storytelling advice, but Wajnberg doesn’t manage the execution.

0 Comments