The third English-language instalment of Shigeru Mizuki’s gargantuan manga history of Japan’s Showa era (the period from 1926 to 1989, defined by the reign of Emperor Hirohito) is the best yet. This sprawling series gradually deepens its gripping narrative as new layers and perspectives are added to a story that is relatively unknown to most Westerners. Part autobiography and part history lesson narrated by Mizuki’s famous yokai character Nezumi Otoko (literally and visually “Rat Man”), each Showa volume demonstrates how the political becomes personal by juxtaposing historical facts and events with the narrative of Mizuki and his family. But where volume one (covering 1926–1939, including the Depression years and the lead-up to war) was too often bogged down by a lengthy and rather uninvolving recounting of historical facts, and volume two (1939–1944, with a focus, naturally, on the Pacific War) suffered from a seemingly endless series of masterfully drawn but ultimately indistinguishable battle scenes populated by anonymous soldiers, the third instalment of the planned four-volume series takes the reader through a riveting account of the final decisive battles of World War II and – most importantly for the storytelling – gives more prominence to Mizuki himself.

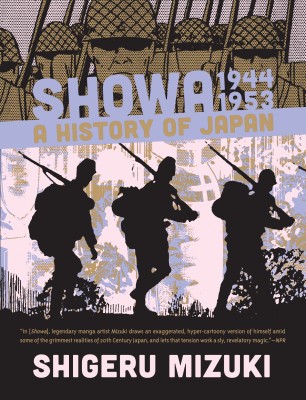

Showa 1944-1953

A History of Japan

Shigeru Mizuki

Drawn & Quarterly

$24.95

paper

536pp

978-1-77046-162-8

Drawn in a style that mixes hyper-realistic back- grounds, often traced from photographs, with cartoony character design, Showa treads a careful visual and narrative line between sombre moments of national as well as personal tragedy and a firm belief that few things are too serious for broad slapstick humour – or, for that matter, to be explained to the reader by a giant rat. As entertainingly offbeat as it is informative and thought-provoking, each new and increasingly impressive instalment reveals Showa to be a singular achievement with a historical and humanistic scope that is perhaps unparalleled in comics. mRb

0 Comments