In the preface to Stolen Family, the author, Johanne Durocher, addresses the subject of her memoir directly: “Just as you have often asked me to, I have written this book to tell your story.” The knowledge that this project was not Durocher’s idea prepares the reader for the product. In narrative and literary terms, it falls short in many ways, but it may serve the purpose it was meant to.

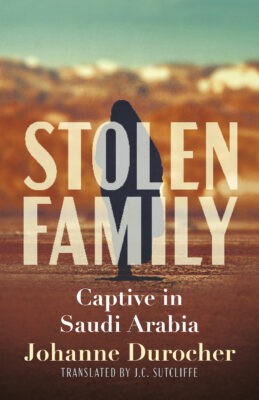

Stolen Family

Captive in Saudi Arabia

Johanne Durocher with Julie Roy

Translated by JC Sutcliffe

Dundurn Press

$23.00

paper

248pp

9781459750425

Nathalie is a fascinating person. She undermines her own best interests repeatedly: she describes horrific abuse at Saeed’s hand, but also seems inexorably drawn to preserve their relationship; she gives contradictory stories to her mother, to various Saudi and Canadian government bodies, and to the media; she lashes out at her mother for not doing enough to help her, while Durocher devotes most of her hours and a great deal of money to petitioning political officials to intervene. In a literary work, such a character would need profound and sensitive development on the page, but in this case, Nathalie and her motivations remain opaque and confusing.

The details of this extremely complex political situation are also difficult to follow. Making narrative sense of them really requires the hand of an investigative journalist with access to experts in Saudi and Canadian law, among other things. Durocher is not the best writer for this job, but one cannot fault her desire to bring as much visibility as possible to her daughter’s story.

Durocher’s pain, as she tries to rescue Nathalie from both her circumstances and herself, is apparent and touching. She periodically runs out of financial and emotional resources for this struggle, and is enraged by Saeed’s treatment of her daughter, the enigmatic behaviour of Saudi officials, and the whimsical interest shown by Canadian media. She is also clearly frustrated by the various ways Nathalie undermines her own case. For example, when a prominent Saudi activist tries to help, Nathalie, apparently in order to protect herself, tells the media that the activist is collaborating with Durocher to kidnap her. This lie places the activist (who has already been arrested for getting involved) at serious risk of imprisonment. Durocher never wavers in her desire to protect Nathalie and her children, but she acknowledges that Nathalie herself sometimes makes everything much harder.

The bulk of Durocher’s ire is reserved for the Canadian government, which she feels has failed to meet its responsibilities. She believes that this failure is due at least in part to discrimination based on Nathalie’s gender, her Quebec citizenship, and especially her intellectual capacities: “I feel as though the Canadian government is prepared to speak out about the fate of people who are members of certain intellectual elite, but not that of a young woman like Nathalie, who didn’t finish school, speaks with a stutter, and got herself into this mess.”

This interesting and troubling situation cries out for a deeper analysis. In the meantime, in fulfilling her daughter’s wish that she tell her story through a book, Durocher has provided a starting point from which another writer might wish to take up this cause.mRb

0 Comments