In Sun of a Distant Land, translator Claire Holden Rothman brings David Bouchet’s heartbreaking and poetic novel, Soleil, to an English audience.

Bouchet’s protagonist, twelve-year-old Souleye, has just immigrated to Montreal from Senegal with his family. When they arrive, they’re filled with hope and enthusiasm and want nothing more than to adapt to their new home, to look straight ahead “without turning back.” But Canada is not the Promised Land they imagined. Quiet and sensitive, Souleye watches his parents struggle to find work and an apartment as black immigrants in a predominantly white neighbourhood. He sees his older brother, Bibi, adjust effortlessly, while he fails to be understood by anyone except his lonely neighbour, Charlotte. He sees his family lose their most prized possession, a hard drive filled with memories from Senegal. And as the seasons pass, he sees his father slowly begin to unravel.

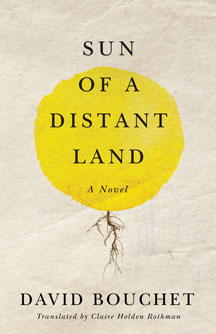

Sun of a Distant Land

David Bouchet

Translated by Claire Holden Rothman

Esplanade Book

$19.95

paper

240pp

9781550654639

Language and communication are central themes in Bouchet’s novel, and this leads to interesting challenges in translation. In Soleil, the French is interspersed with Senegalese phrases, Quebec words, and English expressions. His novel is rife with wordplay and clever turns of phrases, the most obvious being Charlotte’s misunderstanding of Souleye’s name as “Soleil.” In translation, these moments might easily have been lost. Rothman does an admirable job of capturing Bouchet’s layering of languages through various techniques: by adding context or explanations, leaving words in French, and italicizing English words to highlight their importance, among others. While there are some awkward lines and sentences that don’t quite roll off the tongue, Rothman manages to convey the linguistic complexity of the original work, which is so central to Souleye’s experience as a foreigner and minority.

While racism and discrimination in Quebec are touched upon in the novel, Bouchet’s story is never black and white. As Souleye’s family attempts to put down roots, they experience a complicated mixture of isolation, prejudice, and genuine human warmth. In Petite-Nation, they are exoticized and othered, but also welcomed and admired. Souleye’s life is continuously compared to Charlotte’s, whose troubled home contrasts starkly with Souleye’s warm and loving family. Bouchet’s world is filled with contradictions, and this is one of the major strengths of the novel. The borders between languages, cultures, and identities are easily blurred, and we are left with people in all their marvellous complexities.mRb

0 Comments