“I amnot interested in not being a freak,” emphasizes Tara McGowan-Ross during our rambling chat about her new memoir, Nothing Will Be Different. Somehow, that feels like the best way to introduce the charismatic author of a book described as a “neurotic party-girl’s coming-of-age memoir.” Bursting with tales of sex, booze, and everything else one stumbles upon when figuring life out in one’s early twenties, it’s also a reflection on grief, mortality, sobriety, and… the economy. McGowan-Ross ambitiously takes it all on, while sharing stories of breaking up, messing up, and (almost) growing up.

A personal memoir was not the book McGowan-Ross thought she was going to write when she pitched it before the pandemic hit. “I was wrestling with a lot of concepts in far-left politics, especially around purity culture and different socialist themes,” she says; what she initially had in mind were philosophical essays about big ideas, but centred around her own personal experience, similar to how Alicia Elliott wrote A Mind Spread Out on the Ground. It wasn’t until her editor suggested she was “keeping her readers at a distance” that McGowan-Ross altered course. That, and the little lockdown that cut us off from the world for a few fun months:

“I have a hard time being perceived, being looked at,” she says. “I got into writing because I was trying really hard to be understood, to prevent assumptions being made about me. I have severe body dysmorphia, I tend to get flustered when I speak, and I talk too quickly. I didn’t have to think about all that in lockdown. I could relax with my writing and allow myself to be flawed.”

Consequently, the book that, as she puts it, “poured out of her” is raw and honest: a non-linear collection of first-person essays that bounce back and forth across a timeline spanning from the author’s late teens to her late-ish twenties. In a way, it could serve as a kind of how-to for millennial Canadian bohemians: she’s born in Toronto, spends her teenage years around the Halifax punk scene, goes tree-planting out west, and finally moves to Montreal, a city she describes as both “busted and gorgeous.” She dates two different members of the same folk punk band, has sex while listening to Neutral Milk Hotel, goes to poetry readings, starts a magazine, and works multiple random jobs. She drinks way too much and acts recklessly, quotes Nietzsche and sings Joni Mitchell.

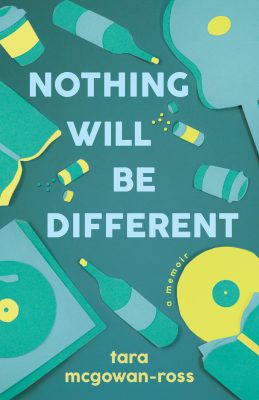

Nothing Will Be Different

A Memoir

Tara McGowan-Ross

Dundurn Press

$21.99

paper

296pp

9781459748736

“I didn’t process my mom’s death until I started writing,” says McGowan-Ross, who was only nine when her mother died of cancer. “I was grappling with this false positivity when talking about it, I kept repeating things that were said to me. Writing allowed me to say ‘this is terrible,’ to be angry and bitter.”

It’s a sentiment that many people who have dealt with death will recognize, that feeling of wanting to protect those who haven’t when speaking about it, instead of honestly sharing how awful everything is. Nothing Will Be Different is almost a grief memoir in that way, with McGowan-Ross as a kind of millennial Joan Didion, walking us through heartbreaking moments in the hospital and the violent consequences of her mother’s death on her family: mainly the author’s developing eating disorder and her brother’s growing addiction to heroin that leads to his eventual overdose.

She doesn’t dwell on the details of her childhood following these tragedies. But she does write that “My grief nags me, constantly, like a child,” and so this child becomes an extra in every essay about her life, along with all the friends, co-workers, and lovers she meets and describes in detail. To have been a part of McGowan-Ross’s life, for better or worse, means that you might find yourself sometimes cheekily, sometimes adoringly described within these pages, with a new name masking your identity and nothing else spared.

“I committed to being honest,” says McGowan-Ross, telling me that aside from her partner and a handful of people, no one else was informed that they might be mentioned in her memoir. “I wrote the truth, and if anyone dislikes it, well, they have an issue with the truth. I’m too selfish as an artist; like, I serve a greater god, I serve art, and I pick art over personal relationships.”

Perhaps this mentality is reflective of her generation, constantly chastised for over-sharing, but also for not just sticking to one thing, one topic, one job. According to her, sure, this could be a grief memoir, but also a book about “the violence of capitalism,” especially in relation to millennials looking for employment after the financial crisis of 2008. In under a decade, she worked as a barista, babysitter, cam girl; she was hired by a non-profit at Concordia and washed windows in Westmount mansions. It might not have always been easy, but she made it work, stretching a small budget to pay rent, travel, go to university, and party.

This kind of versatility is not only demonstrated by an eclectic LinkedIn profile, but the ideas she bandies around. “As a writer, I’m a little bit of an ideas factory,” she tells me. A perfect example of this is a chapter in which she puts the biographical stuff on pause and walks the reader through the history of the Indian Act in the same breezy, familiar, and clever style she later uses to talk about an acid trip or a crusty punk squat. “Race, if you do not know, is fiction written in the late sixteenth century, by the English,” she writes. McGowan-Ross, who is Mi’kmaw and hosts Drawn & Quarterly’s Indigenous Literatures Book Club, says she wanted to clear up her position as an Indigenous writer. “That was me just going off. A settler audience will often pick up a certain settler narrative. There’s this push to gobble up narratives on Indigenous suffering, and I wanted to show that there are different perspectives on Indigeneity.”

The book ends on what feels like the dawn of a new day for McGowan-Ross. Again, you can picture the movie: the sun is shining on a young, now sober woman who’s finally figured it out. The song? “What I Am,” by Edie Brickell and New Bohemians. The twist? It’s March 12, 2020, and her new day just happens to be in sync with a global pandemic.mRb

0 Comments