Stanley Péan is a Quebecer of Haitian origin, and a well-known public figure. He’s the author of numerous novels, short story collections, and books for teenagers; frequently seen on television and heard on the radio; a translator, playwright, journalist, and editor; and he presided over the Union des écrivaines et des écrivains québécois from 2004 to 2010. In other words, he’s been around.

And yet Stanley Péan doesn’t drive a car. He prefers to take taxis, and being such a busy man, he takes a lot of taxis. Over time, he gets to know the cabbies who regularly pick him up on his familiar routes – their stories, quirks, dreams, and foibles. This was the genesis of Taximan, a kind of memoir refracted through a series of short anecdotes about Péan’s more memorable encounters with cab drivers, or “taximen,” as they’re called by the many Haitian immigrants who drive cabs in Quebec. As Péan writes, “The word itself is a gift to us from colonial French.”

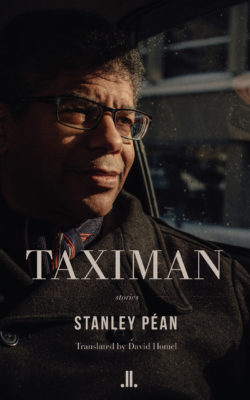

Taximan

Stories and Anecdotes from the Back Seat

Stanley Péan

Translated by David Homel

Linda Leith Publishing

$16.95

paper

140pp

9781988130897

Péan tells these stories without a sense of outrage or anger, because he’s writing as a Quebecer, with a sense of sometimes uneasy but always real belonging, and it is this sense that permeates Taximan from beginning to end. Although born in Haiti, Péan grew up in a remote part of Quebec, with a strict schoolteacher father who insisted he speak French, not Creole. As he explains:

In those days, and it is still the case today, Blacks were rare in the Saguenay Lac Saint-Jean region, in northeastern Quebec. At most, there must have been a dozen Haitian households scattered across the territory: the Cadets, the Dauphins, the Kavanaghs, the Mathieus, the Mételluses, the Norrises […] and the Péans as well, who lived in three different spots in Jonquière and Kénogami. Do you remember that federal minister by the name of Benoît Bouchard who one day congratulated himself in the Commons on the fact that, contrary to Montreal, his region had not been “bothered” by immigration? When you come down to it, my family constituted the entire Haitian community in our little town. You can imagine how difficult it would have been to start a gang of teenage delinquents or even a street demonstration.

Anecdotes can take the reader to many places in just a few lines. Reading Taximan, one becomes aware of how the first wave of educated Haitians arrived in Quebec in the sixties, fleeing the oppressive Duvalier regime. One learns of the absurd imbalance between the numbers of taxi-men versus women who drive cabs in Montreal: “Of the 10,353 drivers in Montreal, only 125 are women.” Péan finds space in these stories to think about writing, Haitian food in relation to identity, jazz, politics, and the multiple solitudes encountered in Quebec. Without realizing it, moving easily from cab ride to cab ride, the reader becomes more aware of a Quebec that is not Black and White, not Yes or No, but is infinitely varied, multi-hued, sometimes absurd, sometimes a little frightening, but still well loved. mRb

0 Comments