Who knew that a book about the taxonomy of mollusc penises, cow throats, intestinal worms, and animal deformities could be so compelling?

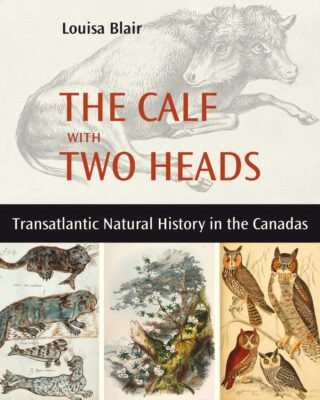

The Calf with Two Heads

Transatlantic Natural History in the Canadas

Louisa Blair

Baraka Books

$29.95

paper

144pp

9781771863308

Drawing from a wealth of documents (the bibliography is impressive), Blair has a knack for finding little-known historical episodes and making them interesting. She keeps things light and accessible and has an affinity for the gritty, muddy side of the early naturalists and their work.

The stories are many and varied. Blair touches on everything from how predicting a lunar eclipse saved Christopher Columbus’ life in Jamaica, to James Cook’s stint in Quebec during the Seven Years’ War, to how fashion trends in Paris drove a demand for hummingbirds, which women pinned to their hats in the 1880s. She describes the world of nature illustrators and painters (often women), the arctic expeditions of Joseph-Elzéar Bernier and Newfoundland’s Robert Bartlett, the trials of Darwin’s lesser-known rival and peer Alfred Russel Wallace, and Quebec’s early, stubborn opposition to the theory of evolution (including from John William Dawson, McGill’s principal from 1855 to 1893).

Blair has a soft spot for underdogs and self-starters, such as Alfred Russel Wallace – who, she writes, “was not independently wealthy like Darwin.” Wallace’s string of terrible luck, including a ship fire that cost him all his specimens and saw him drift on a lifeboat for ten days, partly explains why he is much less famous today than Darwin. Nonetheless, he never lost his passion for observing the natural world, and trying to understand why species of plants and animals changed over time and didn’t remain static.

Wallace was an early progressive and environmentalist. “To pollute a spring or a river, to exterminate a bird or a beast should be treated as moral offenses,” he wrote in 1910. “Never before has there been such widespread ravage of the earth’s surface by destruction of native vegetation … and by pouring into our streams and rivers the refuse of manufactories and of cities.”

Sympathy for mavericks and do-it-yourself types runs through the book. Blair tells the story of the Lady Botanists of Quebec City in the 1820s, including Countess Dalhousie, who spent much of their time searching for and categorizing new species of plants, becoming a crucial source of local knowledge for the director of Kew Gardens in London.

As the anecdotes unfold, The Calf with Two Heads becomes not just about natural history, but Canadian history in general – about how we organized ourselves first as a colony and then as a young nation, and how we built up our cherished institutions, including museums, universities, and libraries.

A fascinating and nuanced portrait of nineteenth-century Canada emerges. It’s become commonplace, in our time, to think that the past was all doom and gloom, oppression, injustice, and suffering. But regular men and women, Indigenous, French, and English alike, often shared common objectives, living and working together respectfully. And when you think about it, life would necessarily have required such collaboration in a land as massive and unforgiving as Canada.

A slim volume that will leave lovers of the esoteric wanting more, The Calf with Two Heads is a refreshing tonic, a cabinet of curiosities that puts our society, history, and relationship with the natural world into perspective. mRb

0 Comments