The muse in our time has taken a conceptual turn. Etymologically, a poet is a “maker,” and many writers are constructing poems from other texts or finding formulas to generate them. Mary Dalton’s extraordinary book uses the traditional rug-making craft of her native Newfoundland as a basic metaphor. Hooked rugs were assembled from strips of cloth, an activity of finding and then constructing a rich mosaic, a cottage industry bricolage.

Hooking

Mary Dalton

Signal Editions

$18.00

Paper

95pp

978-1-55065-351-9

Dalton began her project by thinking about mash-ups in contemporary music. Like any good mash-up, her poems are seamless creations. The works cohere in subtle ways, with their titles usually pointing toward the theme or atmosphere being created. Most of the poems are in stanzas, which leads the mind to expect lyrical tidiness, an expectation usually defeated by the free progression of the poem. We get a series of ghazal-like surprises and our understanding of coherence is expanded. Dalton has cited Christian Bök’s Eunoia, a work of compulsive compilation, as an inspiration. But nothing in Eunoia sounds like this, the conclusion of “Press”: “The jukebox music takes you back; / braver than lipstick, / its threads the colour of cantaloupe and cherry.” The sources are the seventh lines of Gerald Mangan’s “Glasgow 1956,” Alison Fell’s “Pushing Forty,” and Michael Longley’s “An Amish Rug.” The three lines convey nostalgia through complex synesthetic imagery: the music is compared to threads, a visual image, and the threads are compared to lipstick, which is visual and tactile and given colours that are also flavours. Perhaps odour is implied too. We are in the world of juvenile or tawdry romance evoked by the obsolescent jukebox image, one quite removed from the Amish rug in Longley’s original. The use of a poem about rugs in the final line is a clever reminder that we are in the midst of a book founded on a rug metaphor.

Dalton has said in an interview that a cento is a kind of anthology. A reader could spend years going through her poems and their sources. The poems she uses are almost entirely modern, but a poet using her methods could choose poems from an earlier period and the result would be a different range of diction. P.K. Page added the glosa to our repertory of forms. The delights of Hooking may be a new precedent.

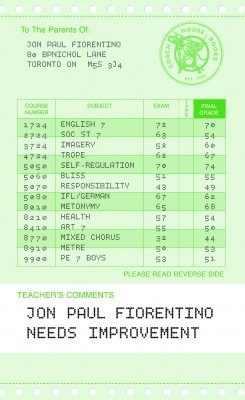

The cover of Jon Paul Fiorentino’s Needs Improvement is a hilarious visual poem. It simulates a traditional report card “To The Parents Of: Jon Paul Fiorentino,” which contains some damning marks: 70 in English, 54 in Imagery, 49 in Responsibility, to select a few. A whole section of this diverse collection is called “Needs Improvement: Pedagogical Interventions.” It contains “The Report Cards of Leslie Mackie,” a student whose progressive destruction by his teachers, parents, and peers is traced in the cards, with their progressively more savage tone. The purpose of the section, the author says in his notes, is to “critique the culture of homophobia, transphobia and bullying in early childhood education.”

Needs Improvement

Jon Paul Fiorentino

Coach House Press

$17.95

Paper

88pp

978-1552452806

The conceptual muse is at work in this book: Fiorentino turns a text by the fearsome critic Judith Butler into a set of poems about “The Winnipeg Cold Storage Company” by manipulating words from her Excitable Speech; other poems rework texts by Oscar Wilde, Roland Barthes, Robert Kroetsch, and William Hazlitt. Confessional poetry is sent up by “Skulk Hour,” a parody of “Skunk Hour,” the poem by Robert Lowell that initiated the movement.

In the final part of the book, Fiorentino presents eight villanelles, as traditional a form as it gets. Three of them use the mottoes of Canadian cities as their refrains, a bit of sampling by our DJ. The mottoes are mocked in two of the poems, but in the final villanelle, “Salter Street Strike,” they are taken seriously. Both are associated with his home city, Winnipeg: “People before profit” and “One with the strength of many.” He associates these modestly utopian slogans with one of his mentors, bpNichol, whose open-heartedness is celebrated in the poem. The book ends, as many books do, with modest hope.

Deena Kara Shaffer’s book is concise and focused on one theme: grief, mainly for her parents, who died of cancer in quick succession. The grey tote of the title is a bag used to pack necessities for a stay in the hospital. Such a bag (maybe the same one), she tells us, was used by the speaker’s father, mother, and grandfather. And the theme of mortality is extended one more generation by “The Grey Tote: / Me,” in which she describes the grey tote sitting in a closet, concealed by “anything that can be put in front,” ready for use for trips and projects, or, by implication, for a trip to the hospital. It’s as much a memento mori as the traditional skull on a desk.

The Grey Tote

Deena Kara Shaffer

Signal Editions

$16.00

Paper

63pp

978-1-55065-352-6

The second section contains the graphic poems about the illnesses of her parents. She avoids sentimentality rather scrupulously, even satirizing her mother’s optimism: “her cancer wasn’t catchable, / but boy, her belief in wellness was.” The administration of dying is outlined in “Ward Calls”: the process begins with apologies for the diagnosis, presumably by a doctor, progresses to the visit by the oncologist “armed / with a social worker,” and ends with Haldol – and as a last minute touch, “a priest to sing you there.”

In the concluding section, she deals with the aftermath of death: the process of grieving, the anxiety about one’s own mortality. Shaffer’s poems are concise, which helps maintain the tone of tough, clear-eyed attention to the realities of dying, but the music is harsh, relying on parallelism and alliteration more than imagery and rhythm. Often the lines are brief to the point of claustrophobia. More generosity of style would intensify the feeling without necessarily leading to soppiness. However, looking steadily at life and death is a form of generosity. The effect of this book is cathartic.

Conjure

A Book of Spells

Peter Dubé

Rebel Satori Press

$13.99

Paper

88pp

978-1-60864-076-8

0 Comments