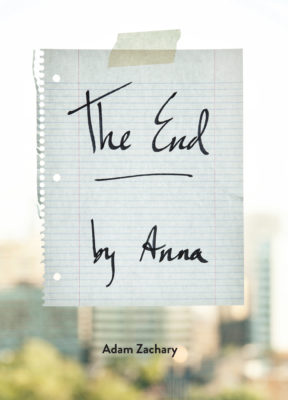

“The End” was to be Anna’s greatest work but she has died before having the chance to create it. Her friend has set out to inspire someone else to perform this unrealized work, in which the artist, alone on the tundra, live streams their death from exposure. In The End, By Anna, Adam Zachary’s narrator gives us the story of Anna, her short life, and her prolific two-year career, its roots in rebellion against a poetry professor who admonished students that writing a poem is like building a house. Anna’s contribution to class in response was a video of the fire she’d set in an abandoned house. “This poem took the form of a house burning down,” she says as she steps into the frame.

The End, by Anna

Adam Zachary

Metatron

$14.00

paper

108pp

9781988355023

The narrator of Maxime Raymond Bock’s Baloney is a young, failed poet looking for a way back to writing, his days now spent parenting, earning money. When he meets Robert Lacerte at a reading one night, he wonders if he’s found the person to guide him.

Baloney

Maxime Raymond Bock

Translated by Pablo Strauss

Coach House Books

$18.95

paper

96pp

9781552453391

The narrator first hopes for a mentor to help him find a way back to poetry, but quickly adjusts his expectations – “I’d found a clown, a character, a subject to objectify.” Lacerte is rather less ridiculous a character than his nickname would have him, however, and when the persona falters, revealing a vulnerable old man, they both “cut the shit” – they’ve become friends. But the young poet is still also hoping for some kind of artistic salvation; whatever else Lacerte’s archives may hold, they are full of “the thing itself, writing, a stubborn impulse that survived under any circumstance, because it had to.” He has a kind of certainty irresistible to someone seeking validation that poetry is worth spending a life on.

Bock gives this story of a small, sad existence all the glorious complexity and contradiction it deserves. Pablo Strauss, who translated Bock’s previous novel, Atavisms, brings us Baloney in spirited English that fully captures the rich and energetic language of the original, an empathetic study of a life in poetry, the dogged commitment and magnificent failure.

0 Comments