The title The Fire That Time invites a reader to think of many things – a particular time in history, a fire, and the work of writer and activist James Baldwin. Baldwin’s classic The Fire Next Time, a collection of two essays published during the period of the US civil rights movement, asked Americans to face and fight the reality of white supremacy that shaped and continues to shape their country. This new collection of writing, edited by scholars Ronald Cummings and Nalini Mohabir, asks readers to consider a particular series of events that happened a half century ago, at the same time Baldwin was writing, and recognize that the civil rights movement did not end at the US border.

The Fire That Time

Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation

Edited by Ronald Cummings and Nalini Mohabir

Black Rose Books

$24.95

paper

200pp

9781551647371

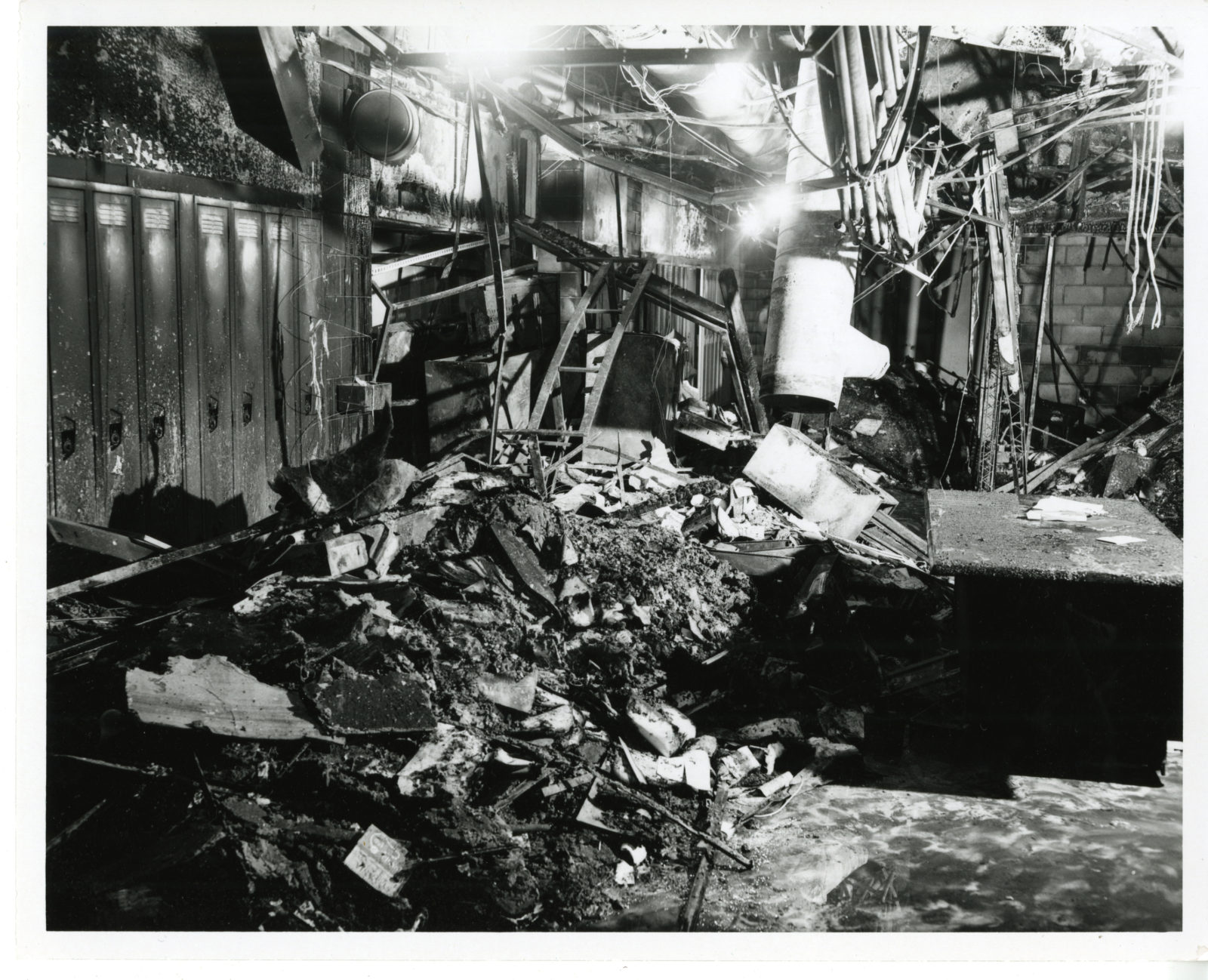

White crowds outside the building chanted violent racial slurs, even calling for the Black demonstrators to be left to burn, and many students were beaten and arrested. Though the majority of charges were dropped, dozens of students were arrested and tried for their involvement, and public opinion focused more on the destruction of computers rather than the reality of racism in Canada.

Editors Cummings and Mohabir, speaking over Zoom, describe how this book was, in some ways, the product of a series of events and an academic conference entitled Protests and Pedagogy, held January 29 to February 11, 2019 to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the occupation.

Fire is therefore key to the approach of the book, both symbolic and otherwise. Through a discussion of fire, many images of oppression and resistance are drawn together. There are literal fires: from the 1734 Montreal fire allegedly set by Marie-Joseph Angélique, an enslaved woman, to the fire in 1969. There are also symbolic ways that fire represents resistance. For Mohabir, it’s about recognizing the significance of what she refers to as a “transnational networked geography that links the Caribbean to Canada.” As she puts it, “what happened in this institution is also connected to a wider social history of fire.”

Nalini Mohabir (photo: Sarah Turner)

As a professor, Mohabir has also noticed that making these connections is important. For her own undergraduate students, “there is interest in terms of what happens in the US in the 1960s and the civil rights movement and protest against Jim Crow and so on, but a lack of understanding about Canada’s role. And that, as [McGill psychiatry professor] Myrna Lashley has said, [the Sir George Affair] was Canada’s civil rights moment.”

To demonstrate the resonance of the Sir George occupation, The Fire That Time exists at the crossroads of scholarship, art, and activism. It engages with history as a means of representing struggle and resistance. Centring on both an event and its legacy, it extends through space as well as through time. As Cummings underlines, “this work also builds on the astute analysis of the students themselves at the time, where they noted the ways in which Canada was part of a white imperialism, part of the colonial structure that they were trying to unthink, because this was also the moment of independence in the [Caribbean] region.”

The idea of a text about what happened in 1969, however, was not a new one – a collection of first-hand accounts and reactions was published by Black Rose Books in 1971, edited by Dennis Forsythe, who had been a graduate student at McGill in 1969. Cummings and Mohabir, while planning Protests and Pedagogy, wanted to invite Forsythe to come and speak alongside some of the other participants of the original uprising. “We reached out to his law office in Jamaica,” explains Mohabir, “and found out that he had died, I think, the day before we made that phone call. So we were suddenly struck with the urgency of how important it was to get these voices on record.”

In the introduction, the editors underline that the book is a result of “conversations, collaborations and networks of support.” The multilayered character of the text is, for Cummings, “shaped by a particular form of interdisciplinarity. Nalini is a postcolonial geographer. So this thinking about space and temporalities and layered histories, I think, is central to her work in perhaps a parallel way to some of the thinking about genres and voice that’s important to my work as a literary scholar. That textured dimensionality of the text is linked to that collaborative practice that we share as editors. But it’s also linked to some of the organic ways in which the book emerged, and also our awareness of it as a community text that we weren’t just producing for the academy.”

This is indeed a rich text. The volume begins with poetry from Kellough, followed by a wide-ranging introduction, providing context to ground the reader. Then there are a series of first-hand remembrances of 1969 from the perspectives of Clarence Bayne, Brenda Dash, Philippe Fils-Aimé, and Nancy Warner, who were all students involved in the occupation. There is also an interview with Juanita Westmoreland-Traoré, the first Black judge in the history of Quebec, who in 1969 was a lawyer who defended students against charges following the fire. The book also covers the impact of the “affair,” connecting its events to Guyana, Cuba, Jamaica, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad, and, in an effective and engaging long essay from Michael O. West, the wider international revolutionary events of 1968. It contains dialogue, archival work, artefacts, essays, letters, and even Guyanese academic and activist Walter Rodney’s course syllabus.

Ronald Cummings (photo: Ajamu X)

Not only does the text connect with other spaces, but it also connects histories. “Some of this work was not just about recuperating history,” explains Cummings, “but also trying to think about questions of what can we do with this history… and not in a prescriptive way but in a generative way.” A chapter by writer Alexis Pauline Gumbs speaks not of the history itself, but asks why her grandfather, representative for Anguilla to the United Nations during the 1967-1969 Anguillan Revolution, would never have spoken of the occupation in Montreal. Presenting a range of theories, Gumbs considers why certain histories are spoken and why others fall victim to, as she writes, “diasporic disremembering.”

This is how history is not just the past. Cummings explains: “It seems to me that we do need to learn from that past and also to say that for us, there’s a way in which we encounter this as history, but it’s also a history that we’re still living with. It’s an unfinished history.” The penultimate chapter of the book, by scholar Afua Cooper, presents a list of clear initiatives that Concordia could enact as a means of reparation for 1969 and its legacy. For Mohabir the Cooper chapter is timely, “because we’re in this moment where we’re reckoning with, what does it mean to have these histories directly on our campus? And to have a new dialogue about what it might mean.”

Three years before the occupation, Canadian poet Earle Birney wrote that, for Canadians, “it’s only by our lack of ghosts we’re haunted.” It would seem that haunting arises not from lack, but rather the inability to confront events such as those documented in The Fire That Time. Cummings and Mohabir have compiled a work that speaks to this need to record and reckon with histories.mRb

Top image courtesy of Concordia Archives: Concordia University Records Management and Archive (File 1074-02-049) Damages cause by fire on the 9th floor of the Henry F. Hall building (photo credit: Bermingham Associates)

0 Comments