“Nobody sends flowers after a mental breakdown, and few send get-well cards to a hospitalized person with a mental illness,” Susan Doherty writes in The Ghost Garden: Inside the Lives of Schizophrenia’s Feared and Forgotten. The day I read that sentence, I had just learned that a friend was in the hospital with lithium poisoning. While this friend wasn’t schizophrenic, he’d had mental health problems in the past. I wondered whether I should call, possibly infringing on his privacy. Or should I stay silent and risk compounding his feelings of isolation and stigma?

Doherty’s book galvanized me. I got in touch.

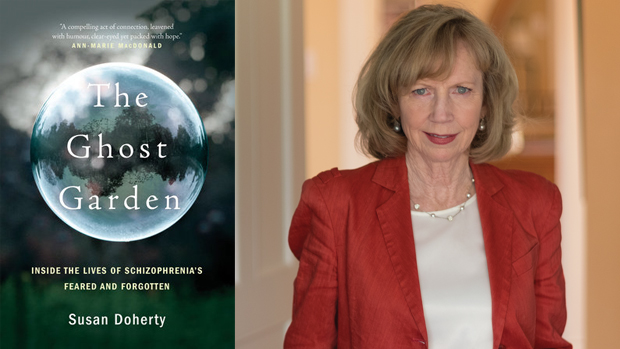

Be warned: reading The Ghost Garden may change you. Susan Doherty, a petite woman with shining blue eyes and a ready smile, is doing big, radical things in the field of mental health – the kinds of things that might inspire you to pitch in and help. At the very least, the book risks challenging misconceptions you may hold about schizophrenia.

The Ghost Garden

Inside the Lives of Schizophrenia’s Feared and Forgotten

Susan Doherty

Random House Canada

$32.95

cloth

360pp

9780735276505

Doherty has a BSc from Concordia, but she also studied journalism and worked as a staffer at MacLean’s magazine. For her novel, she did extensive research in the archives of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute in Verdun. Afterwards, wanting to give something back to the institution, she began to volunteer there. She assumed that the work would be clerical, but John Matheson, the priest who heads the Douglas’s volunteer department, had other plans. He matched her with a woman on a locked ward for the chronically mentally ill. Her job? To make friends.

Doherty soon befriended several other patients on the ward, and learned first-hand about schizophrenia, its symptoms (which can include delusions, hallucinations, paranoia, an inability to focus, and “lack of insight,” meaning patients don’t realize when their beliefs are unfounded), and the often debilitating treatments (with side effects like tremors, substantial weight gain, and potentially fatal loss of temperature sensitivity).

After she started volunteering, a close childhood friend asked her to write the life story of her sister, whom Doherty had first met in 1967, when she was a “bubbly, white-blond nine-year-old with an infectious laugh.” Now sixty, this woman had struggled for decades with mental illness, cycling in and out of hospitals and group homes, and, at one point, was jailed for pouring boiling water into the ear of a roommate. She had a history of violent sexual delusions and symptoms of paranoia that antipsychotics couldn’t fully palliate. Illness, medication, and electroconvulsive therapy had totally transformed the child of Doherty’s memory.

“The easy path,” Doherty writes in her introduction, “was to view Caroline [not her real name] as an incurable, obese, crazy lady, but I couldn’t stop thinking that at one time she had been just like me. In all the most important ways, she still is.”

After some hesitation, Doherty undertook the project. By this time, she’d been volunteering for three years at the Douglas and in group homes, and she felt that she had something to say. The story of the woman Doherty calls Caroline Evans is the book’s core, but we also meet the people Doherty befriended in her volunteer work, each one highlighting an important aspect of schizophrenia. One particularly poetic patient on the ward gave Doherty the book’s title and the metaphor of ghosts. “So often we see the severely mentally ill as less than fully formed human beings,” she writes, “as ghosts of their ‘normal’ selves. As ghosts, they can appear to be inanimate, unreachable, and frightening.”

To deepen her knowledge of the disorder, Doherty took online psychiatry courses from Johns Hopkins University. The theories she learned are mostly set out in the last chapter – a debatable choice, since it’s only at the book’s end that Doherty, who has a lot of informed, thoughtful things to say about treatment, lays out her ideas about the radical paradigm shift needed in mental health, from a mainly pharmaceutical model to an approach more firmly grounded in human contact and friendship.

***

On a cold day in late April, I met Doherty at her home in Montreal’s West End. What, I ask (revealing my own lingering misconceptions), was her most frightening moment at the Douglas?

Her answer is immediate. “The only time I ever felt shaky was the first day I went onto the Psychotic Disorders unit. My own biases were at play, the mistaken idea that people with severe symptoms are unpredictable or violent. That idea is so far from the truth.”

Yet the book opens with Caroline Evans committing a violent crime.

“I wrestled with presenting the reader with such a catastrophic episode,” Doherty admits, “because in reality, psychotic people are victims far more often than perpetrators. With Caroline, I needed to show that what happened could have been prevented.”

Caroline’s isn’t the only violent act in the book. Doherty recounts the case of Vincent Li, who, in 2008, in the grip of psychosis, decapitated and cannibalized a fellow passenger on a Greyhound bus in Manitoba.

“I obsessed about that heartbreak,” Doherty says. “Why wasn’t he able to get help? Where were the resources? My number one reason for writing this book was to show that everyone is reachable. We have to see the person before the diagnosis.”

Li’s absolute discharge in February 2017raised fears vocalized in media across Canada, but Doherty brushes these aside. “When do we ever benefit from fear?” The discharge, she says, shows that recovery is possible. Sustaining recovery will be the challenge, as Li now faces people’s fear wherever he goes.

“Those with psychotic symptoms feel our revulsion, our exclusion, our wariness,” Doherty maintains. “That kind of suspicion means that the broken social threads never have a chance to mend. Violent eruptions are no more prevalent among the psychotic than the non-psychotic.”

Doherty has spent eight years in close contact with schizophrenic patients, and her compassion is contagious. But her talent and equanimity may be greater than some people would be able to manage. She’s heard lurid accounts of rape and sexual torture. One woman called Doherty in the middle of the night to report that Mick Jagger had climbed through her window and raped her. Doherty didn’t contradict her. “Delusions aren’t lies,” she says. Her friends believe their stories, which, if you listen with care, often reveal clues to their suffering and its origins.

Doherty may be ahead of her time in arguing for a paradigm shift away from the medication model that has prevailed since the 1950s. But she’s not alone. Though

she wasn’t aware of it when she started her work, others are moving in the same direction. In Zimbabwe, for instance, volunteers are revolutionizing mental health care with the “Friendship Bench,” a project in which hundreds of women volunteers (known locally as “the grandmothers”) have been trained in evidence-based talk therapy, which they deliver for free in over seventy communities across the country. Inspired by this model, authorities in New York City now offer free mental health therapy training to volunteers so they can support vulnerable peers under the ThriveNYC plan. Doherty’s work in Montreal may turn out to be part of a global groundswell. mRb

0 Comments