The Gift is Zoe Maeve’s debut YA graphic novel about Anastasia Nikolaevna, the fourth daughter of Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov, the last tsar of Russia. This first-person account unfolds initially in the cold opulence of Alexander Palace, with its grand halls and sweeping staircases. The reader is carried into the story on the wings of a moth on the cold, still January day of Anastasia’s birth.

She is a disappointment to the Romanovs, who want an heir. Fortunately, her brother Alexei is born a few years later. Life in the palace is not particularly exciting for the Romanov children. Guards patrol the perimeter, and the family cannot leave the grounds. Their once-cherished carriage rides into the city cease when the revolutionary uprisings begin.

The comic artist adds panels depicting the unrest in the streets, but offers no text to better situate the young reader. This may be because the story is the first-person account of Anastasia, who is sheltered from outside life. But Anastasia knows that something is afoot from overhearing conversations and catching glimpses of photos in military reports that cross her father’s desk. She also helps her mother and a maid sew family jewels into clothing in case they have to leave in a hurry.

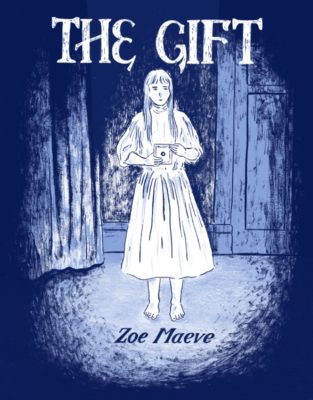

The Gift

Zoe Maeve

Conundrum Press

$18

paper

90pp

9781772620559

The comic artist draws beautiful details of the tsar’s home; the pattern of the ballroom floor immediately comes to mind. Historical details in clothing, furnishings, jewellery, and everyday items are also well done – Maeve’s background as a painter definitely shows through. The choice to print the story in various shades of blue also helps to evoke the cold austerity of the palace. I particularly liked the use of moths showing Anastasia’s spirit to both open and close the story, even though a moth in January is a flight of fancy.

Unfortunately, the story itself is flat and lacks momentum to keep the reader interested. The titular gift, the camera, in no way builds suspense. The photos Anastasia takes offer nothing revelatory to keep the story moving. The camera and Anastasia’s haunting seem superimposed, even though there are countless ways that they could have been combined to much greater effect. Readability is also an issue. Although the comic artist did a wonderful job of changing her layout very creatively, at times the reader does not know whether to read from left to right, or up and down the page.

The Gift is very ambitious for a debut graphic novel. However, if the comic artist had chosen to stray from historical facts, as she acknowledges in the afterword, she could have taken much more liberty. Maeve did a great job of creating a very cold, confined setting, but the story is missing the magic that many young readers would expect in the story of Anastasia. The Gift feels too close to the actual story of the Romanovs.mRb

0 Comments