In one of the conversational poems within Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch’s latest collection, The Good Arabs, the speaker confronts the assertive nature of the collection’s title:

“What about the good Arabs?” you ask.

“What would I know about good Arabs?”

“Is it not the title of your book?”

“Oh. That.”

“I didn’t want it to be an easy title. I didn’t want it to be an easy book,” they say, knowingly, when I mention it. And though the book is not easy – among many other things, it is a serious and plangent love letter to Lebanon – El Bechelany-Lynch has a keen eye for mood and finding lightness.

Across all their poetry, but especially in their nine “Conversations with Arabs” poems, El Bechelany-Lynch looks at issues within their own poetic project, directly taking part in the concerns of their reader and revealing some immediate moral and poetic concerns of the text. Formally, El Bechelany-Lynch refuses to let the book be didactic by building poems in which their speaker can playfully reckon with some of the more overt criticisms in the text – namely, of Western views of the Middle East and moral contradictions in religion, education, media, and values within Arab culture. By placing their speaker in meta-critical situations, El Bechelany-Lynch is explicit that nothing in the text regarding morality is certain, allowing the rest of their poetry to be expansive, emotional, and grave without being declarative. Later in “Conversation #4,” they write,

“So you don’t know the answers?”

“I do not.”

Throughout The Good Arabs, there is a sense that instinctual, unselfconscious questioning is the ideal interpretive mode. Their poetry suggests that following the most intimate, unfinished lines of thought outward, towards a community, might bring us closer to collective truths. They write, in a later poem,

we are wiser & so we think & so we are

wrong & the energy it takes to fight across

a table about the importance of human

life is disastrous & yet we must do it & yet

we must try & yet the times I’ve fought

have unleashed, out of me, a storm

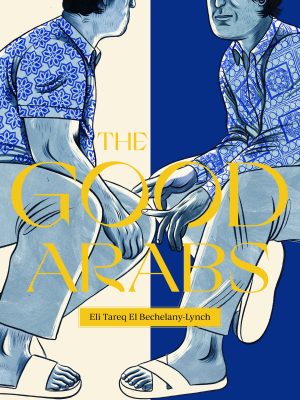

The Good Arabs

Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch

Metonymy Press

$17.95

paper

208pp

781999058890

early sunshine, register the hum of your body underneath mine

*

you say no matter how many times we wake up side by side, it’s still a sweet and slightly exciting thing, right?

*

you said your lungs were just so filled with fresh air out there in the woods

*

she slapped me with her plastic sandal and it didn’t leave a mark

*

the pieces of building you touch are centuries old

*

the needle touches the record but no sound emerges

I met El Bechelany-Lynch in Parc Jarry near Parc Extension, a Montreal neighbourhood where a handful of poems in The Good Arabs are set. They are forthright and comfortable when discussing their work, a gift well suited to their trajectory as a poet. Since graduating from the creative writing program at Concordia a few years ago, feedback and collaboration have continued to be central to their process. They have put out two books in two years (their first, knot body, was published last fall), attended a Banff residency, and participated in a plethora of poetry readings. Beyond their résumé, El Bechelany-Lynch is deeply involved with their close-knit writing community made up of primarily other POC and queer writers; the community they are “writing with and to.” They reflect on their editorial process, saying, “I would never think my work is done,” as it is often passing through other hands.

The Good Arabs has been underway since their time in university; El Bechelany-Lynch calls it “the project I was always writing towards.” Though they stepped away from The Good Arabs to complete and publish knot body, El Bechelany-Lynch is clear when they describe it as a crucial project, conceived of in tandem with their idea of poetry. Interlocutors are nodded to throughout, both directly and indirectly. One poem calls back to Claudia Rankine’s “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely,” another takes on the form of an ampersand-studded Danez Smith poem. Moving through the collection, it is easy to sense the years shifting influences and historical events that have imprinted on the work at different stages. Coming to terms with this collection in the year following the explosion in Beirut, already worn after writing knot body, El Bechelany-Lynch took some reprieve from the work on the poems. Instead they turned to prose.

What resulted is the short story found in the middle of the collection, “Do You Run When You Hear the Sound of a Large Crack?” Unlike the poetry, which mines memories for recurring feelings, questions, and images, it is speculative fiction set in 2040 Lebanon. El Bechelany-Lynch explains, “I was interested in putting characters into a story who live with the background of everything that is present in the poems.” The setting is seamlessly recognizable from the poems, the characters feel familiar, but the story has shifted: Lebanon is amid a second civil war that began after the 2020 explosion. Political unrest abounds and the central characters are grief-ridden, surrounded by death. Although formally abrupt, the story is impactful, driven by the same curiosities as the poetry but moving in the opposite direction: where their poems scour memories, their prose imagines a future. It is indicative of the way El Bechelany-Lynch experiments with form to consider diverging facets of a recurring idea or image.

Beyond the rigour with which El Bechelany-Lynch confronts the global, The Good Arabs is a stunning act of portraiture: of the speaker, of family, and of community. Each person that drifts through their poetry becomes familiar, important. If the book speaks to diasporic experience, it does so by offering a vivid account of familial love, one that spans geographies and includes both chosen family and spectral traces of ancestors.

In the poem “It was,” they write, “we joke about swapping out everyone we don’t like in this city for everyone we love / living elsewhere. The list grows longer and longer until we have to stop, heavy.” In The Good Arabs there is always a joke, and always heaviness. There is also always the speaker, with an inimitable charm, ambling down empty Montreal streets, gyrating to Nancy Ajram, unfurling in the arms of a loved one, slurping pork fat from a bone. The poem continues, “Montreal is a transitional city. I’m still here.”

There, in the poem, I am reminded of the ephemerality of this city, how often literary communities within it change. Later, sitting across from El Bechelany-Lynch, I am reminded of how delightful it is when voices like theirs appear and take root.mRb

0 Comments