The Keys of My Prison is the latest Canadian noir thriller to be resurrected by the Ricochet Books imprint of Montreal’s Véhicule Press. Established in 2010 and curated by Brian Busby, the Ricochet series has brought such long-lost titles as Sugar-Puss on Dorchester Street and Blondes Are My Trouble back into the public consciousness. These novels were originally published by imprints such as Harlequin (before it found its calling in the field of romance novels) and News Stand Library. Once, they were tempting fare for bored travellers, gracing wire racks in train stations and bus stations across the land. In recent years, these books were only available as rare, tattered copies circulating in collectors’ circles.

The Keys of My Prison was originally published by Doubleday in 1956, and it is notably the first in the Ricochet series by a woman author. Frances Shelley Wees was a practised writer, whose first novel, The Maestro Murders, appeared in 1931. She produced some two dozen books (romances, mysteries, and more) over her long career, during which she also worked as a schoolteacher, wife, and mother.

The book works on the reader’s subconscious doubts and fears about the presumed integrity of the male patriarchal figure. Rafe Jonason is the perfect man – in the words of his loving wife Julie, “He was a wonderful person, sweet and good and kind and thoughtful and clean and loving and perfect. He was simply perfect.” He loved Julie despite her hideous facial blemish (only recently corrected with cosmetic surgery); he was a loving father to their son Hugh; he took over the management of the family business under the stern guidance of Julie’s father; he didn’t drink or smoke or chase women – in every way he was exemplary.

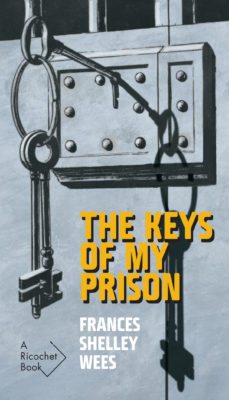

The Keys of My Prison

Frances Shelley Wees

Ricochet Books

$14.95

paper

208pp

9781550654530

Loss of memory and even a profound alteration of character aren’t unprecedented in cases of brain injury, but Julie Jonason is unable to set aside her deep misgivings, even when Rafe seems to have recovered his former sweet self. With the aid of the Holmesian psychologist Doctor Merrill and his assistant Henry Lake, Julie delves deeper into the secrets her husband has kept from her and, indeed, from the world.

Well before the second wave of feminism, The Keys of My Prison imaginatively probes the discontent that Betty Friedan would later address in The Feminine Mystique. Wees, writing in crisp, economic, modern prose, uses a culturally scorned genre to unpack the fears underlying the expectation that women should be unthinkingly loyal to husband and father. Its slow-burning climax exposes the subterranean social forces that can prey on such naive trust. “She had not known it was possible. When people acted with serenity, apparently easy and relaxed, she had thought they were truly so.” The germ of a new awareness might be born from such painful revelations. mRb

0 Comments