Daniel Grenier’s ambitious debut novel spans thousands of kilometres across North America and hundreds of years of history as it reflects on the nature of memory, love, and mortality. The Longest Year received several prize nominations and won the prestigious Prix littéraire des collégiens when it was originally published in French in 2015, and it is a worthy addition to the current gold rush of contemporary Quebecois literature now becoming available in English translation.

The Longest Year is made up of two separate narrative threads, one set in the contemporary world, and the other stretching back through the centuries. The initial story is set in motion when young Gaspésien Albert Langlois arrives in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1980, drawn to the American south by his genealogical research on a mysterious ancestor. Albert marries a young woman and the two have a son, Thomas, who is soon left an orphan to be raised by his devout and emotionally distant grandparents. Thomas takes these traumas in stride, and the first quarter of the novel charts his suburban coming of age.

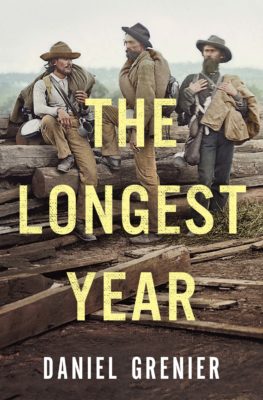

The Longest Year

Daniel Grenier

Translated by Pablo Strauss

House of Anansi Press

$22.95

paper

384pp

978148700153

Throughout the book, Grenier evocatively differentiates the many historical periods in which Aimé’s story is set. The cold and dismal streets of occupied eighteenth-century Quebec City feel completely different from the bustling streets of prosperous Montreal a century later. In particular, Grenier’s description of the building of the Lachine Canal is a bravura performance.

Written in a stylish narrative voice, conveyed here through an excellent translation by Pablo Strauss, The Longest Year evokes the literary yarns of the nineteenth century. Relying heavily on exposition with little dialogue between characters, the novel tells far more than it shows, a perfect technique for spinning the tall tales of Aimé’s world. This panoramic view is somewhat less successful at capturing the life of Thomas Langlois, whose story bookends the adventures of his larger-than-life ancestor. Even with some ups and downs, Thomas’s humdrum daily life in Chattanooga appears to be in black and white next to Aimé’s Technicolor adventures.

At times it might seem that Aimé is at the centre of far too many significant moments of the past; for instance, his experiences during the Civil War serve as the basis for both Stephen Crane’s landmark novel The Red Badge of Courage and Buster Keaton’s classic film The General. But such coincidences are common in historical fiction, and it’s to Grenier’s credit that, although far-fetched, these moments are skillfully crafted, allowing readers to happily suspend disbelief. Another enjoyable aspect of the book is the frequent references to existing fictional characters, such as the bootlegging Gursky brothers of Mordecai Richler’s Solomon Gursky Was Here.

The Longest Year is widescreen historical fiction at its finest. Grenier’s inventive fabrications are richly compelling, and the novel is full of wit, whimsy, and a wellspring of historical detail, both real and imagined.

0 Comments