Haiti occupies an important place in the consciousness of the Americas. Formerly known as St. Domingue, it became independent in 1804 when its former slaves defeated Napoleon Bonaparte’s army, the French general’s first major military defeat. The people of this small country bear the distinction of being the first in the history of humankind to successfully carry out a slave revolution.

But as a Haitian labour organizer remarked to me during my recent visit to that country, knowledge of the Haitian Revolution cannot put food in hungry bellies. The poverty in Haiti is overwhelming; proportionately there is little else like it in the Americas. Haiti is also known for the infamous Duvalier dictatorships, coup d’états, corruption, and stereotypical conceptions of its religion, Vodou. But to say this while ignoring the long history of outside intervention by countries like the United States, France, and Canada is to say nothing. For much of Haiti’s history, outside political, economic, and military interference has served foreign interests and propped up repressive governments, undermining the population’s capacity to exercise its humanity.

Haiti is also a place of tremendous creativity. Out of necessity, the country’s poor have had to find ways to survive economically. There are districts such as Croix-des-Bouquets or the slum district of Grand Rue where art is literally a way of life and where artists are literally surrounded by their art. The larger-than-life sculptures produced in Grand Rue are made out of discarded objects of all kinds, including scrap metal and rubber from nearby auto-shops. These works of art are visually stunning and evocative, examples of creativity out of necessity, the ties that bind art and freedom.

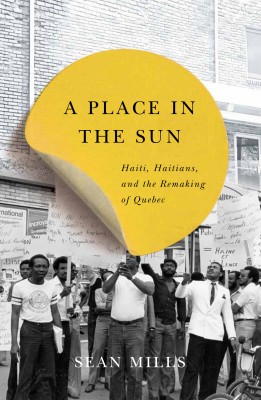

A Place in the Sun

Haiti, Haitians, and the Remaking of Quebec

Sean Mills

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$29.95

paper

330pp

9780773546455

Of course, Dany Laferrière is the first person who comes to mind for Quebeckers when we think of Haitian writers, but there are others such as poet and publisher Rodney Saint-Éloi, who was recently inducted into the Académie des lettres du Québec. Laferrière, Saint-Éloi, and novelist and poet Marie-Célie Agnant, and poet and essayist Joel Desrosiers, among others, all call Montreal home. Together they are part of another Haitian tradition – exile.

Haitian exile is the subject of Sean Mills’s latest book, A Place in the Sun: Haiti, Haitians, and the Remaking of Quebec. This thoroughly researched and well-written history picks up where his first book, The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal, ended its discussion of various groups – women, Black Anglophones, global anti-colonial thinkers, etc. – that influenced Montreal politics in the sixties. During this same period, thousands of Haitian women and men fled the dictatorship of François Duvalier and later his son, Jean-Claude.

The first wave of Haitian exiles, largely intellectuals and professionals – writers, poets, teachers, academics – arrived in Quebec in the midst of political and cultural revolution. They taught in high schools, colleges, and universities at a time when Quebec was in dire need of skilled workers, and their literary circles exposed Québécois writers to the world of Caribbean thought and literature. Haiti’s loss became Quebec’s gain.

The second wave of Haitians was not part of their country’s elite. They became taxi drivers and labourers who, competing with French Quebeckers for jobs, were often greeted with racial hostility and disdain. In response, taxi drivers, for example, organized themselves to fight discrimination within their industry. As Mills shows, they and their supporters were intellectuals in their own right. In the pages of the magazine Le Collectif they discussed worldly events and made links, for example, between the writing and politics of Frantz Fanon and Angela Davis and their particular experiences in Montreal.

Mills also highlights the role that Haitian women played in building and sustaining Montreal’s Haitian community. The women were organizers and intellectuals, many of whom had been part of anti-Duvalier political groups and movements in Haiti. In Montreal they became the backbone of several important Haitian community organizations and many of them are still active today in organizations such as Maison d’Haïti. Mills sensitively narrates their rightful place within the historical narrative of Haitian exiles in Montreal.

Collective organizing by Haitians in Quebec and its impact on Québécois and Canadian nationalisms is central to A Place in the Sun. And yet one of the most intriguing parts of the book hinges on Dany Laferrière’s rise to fame as a Quebec writer. Mills traces Laferrière’s trajectory from a journalist who fled the Duvalier dictatorship to an aspiring novelist trying to make ends meet before ultimately achieving success with his controversial 1985 novel Comment faire l’amour avec un Nègre sans se fatiguer (How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired).

Laferrière was not part of Haiti’s more established exile literati. He worked odd jobs for a while before devoting himself to writing his way out of obscurity. Laferrière’s novel both mocks and, as Mills suggests, reinforces sexual and gender stereotypes as he pierces through taboos associated with Black male–White female sexual encounters and the seemingly primal fears that govern this society’s preoccupation with sex and race. The book was written at a time when the left wing of Quebec nationalism had waned, and Quebec society was apparently ready for a less politically charged but nonetheless socially subversive rendering of Montreal society with a Black male as the chief protagonist. As is often the case with writers, Laferrière’s book came to embody the dreams, aspirations, and contradictions of a Quebec society struggling to redefine itself in the aftermath of the Quiet Revolution.

A Place in the Sun is an important contribution to Quebec, Canadian, and Haitian history. It brings the “other” Quebec into conversation with the dominant nationalist narrative, and in the process changes that narrative. It forces us to reconcile the past with our present, and to imagine possible futures that reflect the reality that there are many peoples who have made Quebec, and in the process made Quebec their home. mRb

0 Comments