The worst writing advice Louise Penny ever got – to abandon any hope of seeing her work in print – came early in her career, back when she first decided to give creative writing a go. “There are a lot of people who went out of their way to tell me that I wouldn’t be published,” Penny recalls. It was a difficult time for her; she was being hounded daily by her inner critic, and she still doesn’t know what motivated her peers’ pessimism. “I don’t know if they were aware that they were shooting down something very fragile and vulnerable, and that gave them pleasure, or if they really thought they were doing me a favour.”

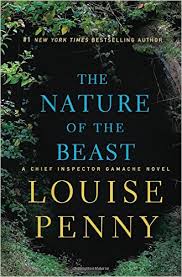

Either way, Penny ignored them. And a good job she did. Her internationally adored Chief Inspector Armand Gamache series has sold over 2.7 million copies and has been translated into twenty-five languages. In August, the eleventh book in the series – The Nature of the Beast – launched to accolades from reviewers and fans alike and debuted at third place on the New York Times Best Seller list for hardcover fiction.

The Nature of the Beast

Louise Penny

Minotaur Books

$27.99

cloth

384pp

9781250022080

Penny’s starting point for The Nature of the Beast was the same as her starting point for every book: “a lump in the throat,” she says, borrowing a phrase that Robert Frost used to describe his creative process. “It has to be something I feel strongly about; some emotion or some ethical issue,” she says. “It can’t be simply a killing or else I would lose interest in about five paragraphs.”

Invariably, the source of the emotional conflict that seizes Penny’s imagination and drives her to spend an entire book understanding it is a poem. “Poets render emotion down to, sometimes, a line or two,” she says, admiringly. “I read poetry out of pleasure but I get so many ideas out of poetry because it’s about emotion – strong emotion.”

Though they don’t always make it into the final draft, every new book has an accompanying couplet that serves as an emotional compass when she is writing. Penny transcribes the couplet on a Post-it note and affixes it to her laptop “for when I get lost in the middle.” The inspiration for The Nature of the Beast was the last two lines from the poem “The Second Coming” by W. B. Yeats: “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”

Although Penny now turns to poetry for creative nourishment, her original source of inspiration was crime fiction. After several years of unsuccessful attempts at historical fiction, everything fell into place on the day that Penny looked at the stack of books on her bedside – which at various times included titles by Agatha Christie, Georges Simenon, Ngaio Marsh, and Dorothy L. Sayers – and realized the answer was to embrace the genre she loved.

She resolved to write a book that she would enjoy reading, even if it never made it to print. And then, she says, “I put myself into everything. Every character, every emotion, every bit of jealousy and rage and murderous thought, every bit of bile and every bit of forgiveness.”

As she wrote, it became clear that although her main character was a police officer and the plot centred around murder, what her writing would really explore was not police procedure but the duality of life. “My books aren’t really about the blood; they’re about the marrow,” Penny explains. “The gap between what people say and their actions, between what they think and what they feel. And that is informed by my life. My daily life is filled with things that are hilarious and things that reduce me to tears, sometimes within an hour of each other.”

Indeed, Penny’s books are famous for their sudden flashes of wit, wordplay, and occasional all-out silliness. In The Nature of the Beast, a character who traipses through the woods in a ridiculously bright pink woolly sweater is said to look “like an escapee from a Dr. Seuss book. On the lam from green eggs and ham.”

Her genre-bending approach is now beloved, but it proved to be a disadvantage when she was first seeking a publisher. “I sent [the first book, Still Life] out to every agent and publisher internationally. No one wanted it. It was turned down by everybody,” she recalls. Her luck changed when she placed second in the UK’s Debut Dagger competition for the best unpublished crime fiction manuscript, attracting the attention of a literary agent and, ultimately, a publisher. At that point, Penny reports, “what had been its handicap became its strength. Once someone saw what it was, it created in many ways a genre unto itself.”

Penny laments that a downside to having a flourishing career as a crime writer is that she can no longer read crime fiction – especially not her contemporaries, whom, she says without irony, she is “dying to read.” “I don’t want to be influenced,” Penny explains. “I’m very impressionable.”

On the plus side, Penny has been delighted by the rich connections she has made with readers through her author Facebook page, particularly those who, upon learning that Penny’s husband Michael has dementia, have written to offer the wisdom and empathy of their own similar experiences. “I can’t tell you how wonderful it is, how much compassion there is out there and how much company,” Penny says. “These people are very generous with their own lives, and it’s a very powerful thing.”

After a whirlwind US book tour for The Nature of the Beast, Penny returned home to Knowlton, where she has already begun writing the next Chief Inspector Gamache book. She was tight-lipped about what readers can expect from Gamache and the residents of Three Pines in book twelve, but she did divulge that it has “something to do with maps,” a subject that caught her attention and didn’t let go.

Ideas for new books “come from all over the place,” she says. “Things just kind of appear and I think that’s interesting. Then I explore it and think ‘yes, I could spend a year thinking about this and writing about this.’ Because it is an entire year of your life. You’d better love it. If it doesn’t fascinate you, why would it fascinate anyone else?”

Penny writes every day, whether she feels inspired or not. “There is an alchemy between inspiration and discipline that can result in a good book,” she says. And although she has published a Gamache novel every year since 2005, she feels no slowdown in sight. Even on hard days, she say, “there’s nothing I would rather be doing.” mRb

0 Comments