The conventional wisdom is that history is told from the perspective of the victors. But in Canada the “winning” side doesn’t always control the narrative. Soon after World War II, when Japanese-Canadians were released from internment camps only to be deported back to Japan, massive public protests against these deportations occurred and, in 1950, 1,434 Japanese-Canadians received some compensation for losing their property.While an apology for this shameful treatment and a more complete compensation only came in 1988, this ability to occasionally acknowledge wrongdoing and try to rectify it has long buttressed Canada’s reputation as a nation dedicated to civil liberties.

During the October Crisis of 1970, however, civil liberties in Canada were suspended through the application of the War Measures Act, a first in times of peace.Two recently published books on the October Crisis illustrate just how important perspective is when it comes to such a controversial episode and how relevant the issues discussed back then are today.

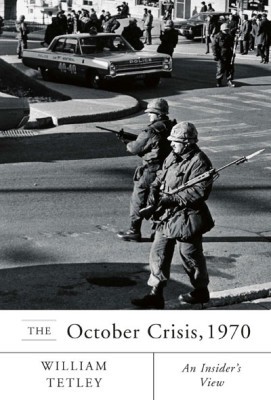

The October Crisis, 1970

An Insider's View

William Tetley

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$27.95

paper

376pp

9780773538016

On the other hand, there’s Trudeau’s Darkest Hour:War Measures in Time of Peace, October 1970, edited by Guy Bouthillier – also a lawyer and president of Mouvement Queìbec français – and Eìdouard Cloutier – a professor of political science at Universiteì de Montreìal.While Tetley’s book reads, at times, like a hagiography of Robert Bourassa, Trudeau’s Darkest Hour is nothing short of a demonography of Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Not only do the editors wonder if “… Trudeau [was] nostalgic for the old days when Duplessis enjoyed triumphant ‘unanimity’,” thereby likening him to the prime minister who ruled over Queìbec during la grande noirceur, but they practically accuse him of autocracy (“The prime minister could quite bluntly but accurately say to the provinces ‘L’Eìtat, c’est moi!’ and you are nothing”) and don’t shy away from quoting an unnamed member of Parliament who, referring to the Trudeau Liberals, said, “I thought I was sitting with a bunch of Mussolini blackshirts.”

Trudeau’s Darkest Hour

War Measures In Time Of Peace, October 1970

Edited By Guy Bouthiller and Édouard Cloutier

Baraka Books

$19.95

paper

206pp

9781926824048

Unlike numerous other state violations of civil liberties in Canada, the October Crisis became legendary, and it seemed that many – including lawmakers who replaced the War Measures Act by the Emergencies Act, which, unlike its predecessor, is subject to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms – didn’t want such an event to happen again.

Until, that is, the G20 summit in Toronto on June 26–27, 2010. Queen’s Park was chosen as a “designated speech area” where protesters could rally and exercise their right to free speech. After the violent actions of a few anarchists, Queen’s Park became a place where badgeless police officers manhandled protesters, whether they had actually committed acts of violence or not, before bringing them to a temporary detention centre. Pepper spray was used on sitting protesters and rubber bullets were shot into the crowd. Students from all over Canada who were sleeping in the University of Toronto gym were woken up by a Sunday morning raid and arrested by police armed with tactical weapons for unlawful assembly or for rioting. In all, more than 1,100 people were arrested, including seventy university students still in their pyjamas, crammed into the detention centre without food (at least for the first 12 hours) and with very little water. Detainees were strip-searched, didn’t have access to a lawyer (because martial law was in force, a police officer allegedly claimed) and didn’t receive required medical attention. In the end, 709 detainees were never charged.

In comparison, 497 people were arrested without warrant during the October Crisis – some in the middle of the night.They didn’t have any contact with their families, let alone a lawyer. Only 62 were charged and the others were released days, even months, later. In a way, the October Crisis pales in comparison to the violation of civil liberties that occurred during the Toronto G20. Indeed, Ontario ombudsman Andreì Marin said, “the most massive compromise of civil liberties in Canadian history” had occurred during the G20 weekend.

The Ontario government’s perspective on civil liberties – like that of the federal and the Quebec governments during the October Crisis – seems to correspond to Tetley’s belief that certain actions are acceptable as long as “… the effect [is] mostly positive and the rights taken away [are] not extensive.” But civil liberties in Canada and elsewhere shouldn’t be privileges that a government grants its citizens as long as its interests are served by doing so.They are rights that every citizen must defend tooth and nail.As Robert Stanfield writes in Rumours of War (excerpted in Trudeau’s Darkest Hour) “Civil liberties in Canada … depend basically upon the importance Canadians attach to them and upon our willingness to defend them even in times of stress. In our search for protection from violence we must recognize that arbitrary abrogation of individual rights weakens rather than strengthens social order.”

From stalling the Afghan detainee controversy to refusing to launch public hearings on policing at the Toronto G20 summit, Canada seems to be trying to change the way it’s telling its stories, making sure that the victors are writing these specific bits of history. But, as Romeìo Dallaire claims in this issue’s cover story,“we will be held accountable in history,” not only internationally, but also nationally. Let us hope that history will also remember how we righted the wrongs recently committed. mRb

0 Comments