When I reached out to Valérie Bah and Kama La Mackerel to talk about The Rage Letters and its imminent release by Metonymy Press, they graciously agreed to meet with me. Both had separately shared their thoughts on translation in Quebec and how their work is subverting it for a Read Quebec piece I wrote for Black History Month. But this time, La Mackerel requested to be interviewed alongside Bah.

We meet on a rainy Wednesday evening at a Creole restaurant called Palme on Sainte-Catherine, right outside of the gay village. La Mackerel arrives first, their smile glowing in the grey weather. Bah arrives once the skies had cleared up. We decide to eat first: cod accras to start, followed by copious plates of griot, djon djon rice, and jerk chicken. It’s only once our plates are empty and our bellies full that we get on with the interview portion of the evening.

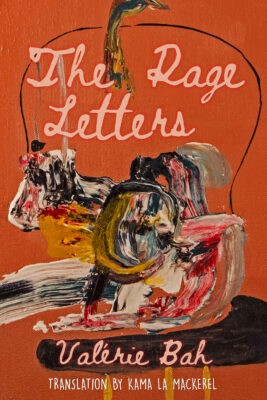

The Rage Letters Metonymy Press

Valérie Bah

Translated by Kama La Mackerel

$19.95

paper

176pp

9781777485276

“Very much note-taking,” Bah replies. “I remember writing a lot of these stories as a very secret practice of just processing… There’s the layer where you live life, and there’s a layer where you are purely synthesizing; it’s like your imagination is constructing life.”

“I do a lot of photo editing,” continues Bah, also a professional photographer, noting that this practice showed up in their creative writing process in the early stages of the book. “There is this part of editing images for me [where] you really do construct something from the reality that you live. For me it was making decisions around the saturation, the mood, and how to tell the story, and I feel like writing is in the same sort of emotional space.”

For Bah, we all tell ourselves stories that follow scripts and forms, whether those of romantic comedies or thrillers. They wanted their writing to go about with a framing of life: “My intention was to write stories, construct riddles around liberation. How does someone in a very banal, realist scenario unlock something that gives them more space, or how [do] they get to see themselves in the front seat?” they ask. “Something I might have internalized growing up in this country, in this territory, [is] seeing yourself as an object. I’m always amazed to see that this is internalized by so many people.”

Looking back on it now, two years after its publication, Les enragé.e.s is a writing initiation for Bah, showing a radical and too often overlooked coming of age within the Haitian diaspora of Montreal. “Growing up here, you feel the sense of a scary project, of the places in you that can’t grow,” they explain. “I feel into those diaspora feelings in the book, and in my everyday of ‘how do I make my family make sense of who and where I am?’ It’s more like engaging with Black migration: humans have a right to love, rest, and fullness. It’s so banal, but so totally opposite of the day-to-day design by the state.”

This evoked extreme feelings of vulnerability for Bah once the book came out, feelings of having given away something deeply personal and held closely. But those feelings paid off: the readers for whom it was written felt seen by Les enragé.e.s.

Kama La Mackerel

These readers included Kama La Mackerel, who explained that “I have never seen myself in a book in Franco-Quebec literature. Everything about it, every single character, all of the dynamics in particular, hit me. And then there’s everything with language, everything with gender that’s not justified, not explained; it’s just there. Yeah, it really really spoke to me in a deep way.”

Coincidentally, Metonymy Press had asked La Mackerel shortly before reading Les enragé.e.s to be on the lookout for French queer literature, as they were intent on publishing their first French-to-English translation. La Mackerel hadn’t even finished the book and immediately jumped on their email to write to the publishers: “‘I found the book, that’s the one!’ I was so sure of it.”

Bah had been following and admiring Metonymy Press long before publishing Les enragé.e.s. Because they wrote the first draft of their book in English, they were actually considering reaching out to Metonymy. “A year before Les enragé.e.s was published, I had a letter of presentation [for] them. I was thinking they would be great for the English version,” Bah recalls. “And for me it’s very interesting that it kind of came up organically.”

When the opportunity to get their work translated by La Mackerel with Metonymy Press came around, Bah was delighted to discover the team’s “ability to work deeply [and see] how much I’ve learned from them and how much support they offered,” they explain. “At this point, the translation, I could have just as easily not been involved, but they really did welcome me on board [and] welcome me in my demands.”

It’s true that the dynamics of translation in literature are quite unique, and not always easy to understand as a first-time author. In fact, many authors do not even participate in the translation process, nor do they wish to, and translators alone have to make difficult decisions to keep the essence of the book authentic.

This is what La Mackerel first struggled with the most, especially while translating a book that so uniquely plays with the French language to subvert it the way Bah did in Les enragé.e.s, using anglicisms, English expressions, those classic Québécois swear words we all love, and much more. Finding how to disrupt the English language in a manner that remains loyal to the original version meant playing with two colonial languages that have their own power dynamics within our province.

“There’s a very specific voice that I hear in the French [version] and that’s the challenge of translation,” La Mackerel explains, “because I can’t capture that voice and bring it into English, but I need to find the other version of that voice in the other language.”

In that sense, translation can sometimes be viewed, as La Mackerel calls it, as a “process of grieving,” because some things inevitably get lost. But some things can also be gained. Bah explains it best, speaking to their translator: “There is something in your poetry and also in the images that you made where you seem very at home in the natural world. You can describe the ocean in a way I couldn’t – I mean, I didn’t grow up around it, and I felt like it showed up in some stories. I think your poetry shows up, like the texture of it, throughout the book.”

Both writers are very excited for the release of The Rage Letters, due August 15th, and are very proud of this very first French-to-English translation published at Metonymy Press. Considering that Metonymy has launched the books of many young queer and trans authors of colour who went on to have successful careers – Kai Cheng Thom, Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch, and Jiaqing Wilson-Yang, to name a few – this could surely give a new breath to Bah’s stories.

Ashley Fortier, co-publisher at Metonymy Press, thought this book was an obvious choice because of “the local component, a particular Montreal experience that hasn’t been written about,” which aligns with the value Metonymy Press sees in their community. This first translation means a great deal for the publisher since it will allow them to leave the very “tight bubble of English publishing in Quebec,” solidify relationships with French publishers, and establish a dialogue with our province’s francophone landscape.mRb

Photo of Valérie Bah: Wry Finkelstein

Photo of Kama La Mackerel: Noire Moulium

0 Comments