There is a restlessness in Susan Gillis’s poems, a reluctance to lay down roots, that doesn’t take long to reveal itself in conversation with the poet. “I think the conditions of travel are conditions that I’ve always sought,” she tells me. “There’s something about the force on the psyche of a place that doesn’t know you or care about you. It doesn’t hate you. In fact, it often welcomes you, but it has no vested interest. That kind of opening is the condition I seek most.”

Gillis’s poems show evidence of travel and how it can sharpen one’s senses. While her first two collections were published in Montreal, both seem to have been conceived elsewhere, as they scramble through the streets and back alleys of other cities. Swimming Among the Ruins, which was shortlisted for both the Pat Lowther Memorial Award and the ReLit Award in 2000, includes poems set in Greece and Turkey, and a section of “Postcards from London.” Volta, which appeared two years later and won the 2002 A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry, finds itself in similar climes, and also includes fifteen “translations” of sonnets by the Earl of Surrey, relocated to British Columbia’s Quadra Island.

If Gillis’s work defies regionality, it may be in part because the poet has ties to many places. Born and raised in Halifax, she travelled across the continent to go to school in Victoria and remained there for some time, undecided about which coast to call home. In the end, she stayed in B.C. for some twenty years, running a vintage clothing business. After another period of transition, and a long series of storage lockers, she resettled in Montreal in 1998. Today she teaches at John Abbott College, and when school’s out, she commutes back to her home base near Perth, Ontario, her feet still planted in two different places. Having two homes works for her, she has decided, perhaps in part because it keeps her a bit out of a routine, a bit uprooted, which drives her work. It is, perhaps, a way of simulating the disruptions of travel while staying close to home.

Closer to home is where Gillis’s latest collection, The Rapids, mostly finds itself, and with its poems she proves herself capable of mining moments of purposeful dislocation from the everyday. She contemplates the Lachine Canal, Habitat 67, or a creaking house on a winter night with the same perplexity as a traveller observing these for the first time. The opening that travel creates can be found in the familiar, she says, “in looking at the same landscape every day and seeing the small differences, particularly when there’s just been rain, and when there hasn’t been rain, and when there’s cloud instead of sun…”

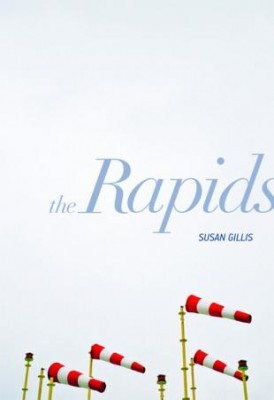

The Rapids

Susan Gillis

Brick Books

19.99

paper

105pp

978-1-926829-79-1

It’s appropriate, then, that white water is a central and recurring image behind the book, as the river’s rapids are literally capable of this kind of swallowing. We know that the Lachine Rapids, in the St. Lawrence River toward the west of Montreal, swallowed at least one of Samuel de Champlain’s men, and they were voracious enough to force travellers to portage around them until the Lachine Canal was built in the 1820s. At times Gillis’s river has this same deadly force, “full of noisy intent / and vortical pull” in “View with Cameos”; “caught in its own thrashing” in “Mid-Winter Dragon”; and in “Spring Storm”:

…the river reared up like a dragon,

scales flapping; the sun, smoke,

the far faint islands, all

collapsed in the froth of its lashing.

I had never been so small,

atomic. I was tossed. I have to

say “maelstrom.” I wanted out.

I wanted time to turn back.

Gillis is especially interested in those moments of maelstrom when life propels us toward dramatic change, when we no longer steer the boat of our own destinies, but are propelled toward action by forces greater than ourselves. She seems to seek the animating force behind the storm, what she describes in “Ars Poetica” as “the push / in the fist-like bud, knowledge / held without knowing.”

“I definitely feel some…” Gillis stops to consider, “surprise isn’t quite the word – when people say, ‘Well, the river’s a metaphor, isn’t it?’ And I think, well, partly. But it’s also partly itself. It’s also the river. I’m really interested in … not erasing myself from a place, but fading a bit into the background of a place, getting to know it on its terms.”

For The Rapids, this meant reading up on the history and geology of the St. Lawrence, at times in great scientific detail. “I found almost randomly in the library a couple of books that were studies of the river’s geology and every aspect of it physically: the flora and fauna, the physics of water flow, the geology of the riverbed – all that kind of science stuff that you can kind of absorb and then forget. I could not have written about the river without knowing that stuff. I think it provided me with a language, a way of looking at them [the rapids] that didn’t just sort of superimpose my human emotional stuff onto them. I didn’t want to just be romantic about them. I wanted to understand as much as I could of the language of that place and the physical phenomenon so that when I was interpreting it, I would have some sense of what it was saying.”

This effort to write about the river on its own terms is related to Gillis’s work with Yoko’s Dogs, a collective of four poets – Gillis, Jan Conn, Mary di Michele, and Jane Munro – who collaborate through the poetic form of renku. Gillis describes the

collaboration as a discipline that has shaken up her habits and assumptions about writing. “I wanted to practice a kind of poetic composition that would allow me to step right out of what I was doing, to practice looking and [using] the image with its own resonance, rather than through its figurative power.” (Yoko’s Dogs will release a shared collection from Pedlar Press in 2013.) Of course it is impossible for the poet to remove herself completely from what she’s doing, but the influence of this discipline is apparent in The Rapids, as the human often recedes into the background, either “wanting form,” like the lonely hotel patron in “Neruda’s Rain,” or, like the tiny homeowners in “A Good Plan,” so dwarfed by their surroundings that human concerns seem hopelessly absurd.

But then, nature’s power often puts our concerns into stark and humbling context. For Gillis, the ocean held this power for a long time, what she describes as “the power to erase the borders between the particulate you and the world.” Now she recognizes a similar power in the river to make her feel small, borderless, elemental. “The river doesn’t do it exactly the same way,” she qualifies, “But that strong flow, that urge from the inland source out to the sea … A river is like a giant muscle. It’s powerful.”

With The Rapids Gillis draws on that power, startling us, jostling us, but ultimately ferrying us smoothly out toward wider, bigger waters. mRb

0 Comments