T he Kurds are a nation without a country, and of course they’re not the only ones in that situation. The territory they live on extends across Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, and when they are in the news, it’s usually bad news: a gas attack or a political assassination. So it’s refreshing to read a lyrical novel from a Kurdish poet who conjures up his lost village, his lost country, his lost childhood, all with subtlety and grace.

This poet turned novelist is Seyhmus Dagtekin, born in 1964 in a small village in eastern Turkey. These days, thanks to immigration and the school that was built in his village, Dagtekin is a Parisian, a poet, and the winner of several major poetry prizes, among them the Prix Théophile Gautier of the Académie française. So though we’re in the kingdom of childhood with this short novel To the Spring, by Night, we’re not in the hands of a naïve writer.

Dagtekin is more like a magical writer. The village and its surroundings described by the young narrator owe a lot to animism, despite the village’s adherence to Islam. Every stone, every cloud, every gurgle of water from every spring hides its portion of truth. And the narrator, both boy and man, is attentive to all of this. The knowledge of the natural world, which is, in reality, a knowledge of myths and fears and stories, comes from adults, who are generous in their stories, especially the scariest kind. There is no natural world in Dagtekin’s story; instead, it is a supernatural world. This sense of wonderment is learned at the elders’ feet. “We were told,” the beginning of many sentences read. And what we are told – we and the young narrator – imbues us with a mix of fear and wonder.

Goats, corn, tobacco, grapes, wheat – the village ekes out its life from famine to famine, from winter to winter. It is a place removed from time. The grave of a local saint oversees everything from the top of the hill. Men pray to God for their goats to be protected from wolves, while the wolves are praying to the same source for relief from their hunger. Who knows which prayer will be heard in Heaven? Both are equally valid.

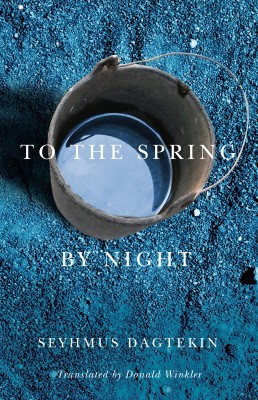

To the Spring, by Night

Seyhmus Dagtekin

Translated by Donald Winkler

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$19.95

paper

200pp

978077354155-9

Everything is frozen in time until, at the very end of the book, modernity enters the village. Paradise is lost when the State decides that the children of this village must learn to read and write. A teacher arrives, and the young narrator thrives on the diet of letters he offers. But there are no teachers without schoolhouses, and to build one, a road is pushed through the mountain pass where, before, only goats and smugglers could squeeze through. Suddenly, this village paradise, which was also a place of darkest superstition, joins the contemporary world because a few kids have learned to read. The boy traces his first letters in the dirt at the teacher’s feet, and, suddenly, the gates spring open. A Kurdish goatherd can end up as a poet in Paris, writing a moving memoir we can all read. mRb

0 Comments