To the Boys Who Wear Pink is the story of a party. Revolving around a core of eight former self-identified kings of high school, the night is narrated through a string of twenty-four voices as each attendee is given a chance at the narrative auxiliary cable.

It begins with one of the eight, Ryan, summing himself up in the mirror. There is an immediate sense of time having passed, a gilded era having settled into the photographs framing Ryan’s reflection. But once he arrives at the house party, the collective energy of these men – how they watch each other, how they feel with each other, what they make each other become – gives one a sense of how things used to be. They are together again, and suddenly the past isn’t so far away. They can hear it in the alcohol and drugs. This also means that the reason they were estranged, the reason why they haven’t seen each other in a while, accumulates in their collective mind throughout the night.

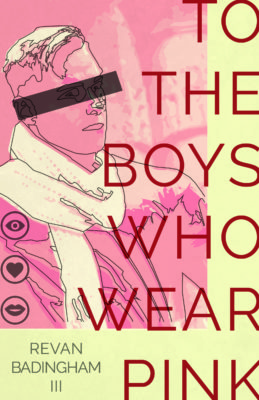

To the Boys Who Wear Pink

Revan Badingham III

Riley Palanca

$23.69

paper

286pp

9781777027902

As each character reveals himself and his fears, the reader develops a very human omniscience, the kind one might have if one were part of the group; for example, the way the chapter-by-chapter repetition that Sugar is “impossible to hate” repeats into a reputation, or how everyone agrees that Angelo is hot, despite his negative self-perception. Sometimes, the voices push the edge of caricature, which maybe is just a function of the way we can become characters to ourselves, especially when we feel ourselves to be under adolescent-like scrutiny.

Other voices haunt the evening, too; P!nk songs title each chapter and are incorporated into the chapters themselves, and, like a real tracklist, they colour and affect the shape of the night. Also on repeat are the words of a character who isn’t at the party, or might be, who was fond of grand statements and was never given the chance to grow out of his world-weary one-liners that sometimes mimic P!nk’s own snappy growl.

Revan Badingham III, the real emcee of the evening, deftly intertwines lives while also keeping the party moving, writes lovingly about every high school type – the jock, the loner, the pretty boy – and, maybe most wonderfully, has such an intimate understanding of the lifespan of a party. The too-early crowd, the stress of the host, the too-drunk friend who is fielding a larger grief. The private moments in hallways and bathrooms, on porches, the walk in the middle of the street at dawn. How someone always ends up in the pool. To the Boys is fun and unafraid to be sexy. It’s sweet-bitter-short, like a shot and its chaser. mRb

0 Comments