“I‘m a trauma castle. It’s all in me, constantly, I can try to hide it, but it’s always there. I travel back in time in the lapse of a second. I’m also a fortress now, I’ve learned so much to protect myself from the exterior. It’s both a blessing and a curse; I protect myself from harm, but I rarely let anyone in. It’s a trauma castle adorned with broken windows. It’s still standing.”

Trauma Castle is a zine I’ve bought several times as gifts for loved ones. When I brought it home the first time, my partner read the zine over my shoulder one evening and was rendered speechless. She was speechless for two reasons: she was shocked at the violence Billy had experienced as a child, which they were describing in the zine, and she was impressed that the intimacy, terror, and complexity of that violence were being shared. It’s rare for violence experienced as a result of poverty to be laid out without demonizing the perpetrator. It was done in the beautiful, critically acclaimed film Moonlight, though one of its only major downfalls was the portrayal of the mother as a terrifying demon, instead of a struggling human being without support. It’s rare that people in poverty are granted the respect of being portrayed with the complexity and humanity they deserve, especially when they harm one another. For that reason, among others, Trauma Castle is a refreshing gift.

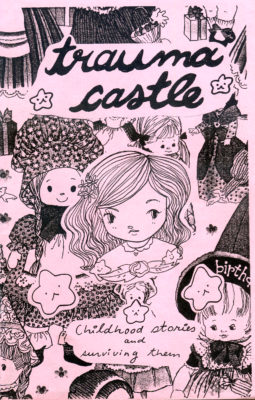

Trauma Castle

Childhood Stories and Surviving Them

Billy Starfield

Illustrated by Starchild Stela

FemmeCrimesDistro

$5.00

zine

36pp

Collaged images and illustrations surround the writing in Trauma Castle. The layers of childhood nostalgia found in the imagery remind me of bedsheets and wallpaper from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Starfield is a well-known Montreal graffiti artist, visual artist, and zinester. They elevate femme identity and so-called “feminine” aesthetics in a masc-obsessed queer culture. Their work generates support and space for other people to be visible and free.

We met at Café Touski on a sunny late summer afternoon and sat outside.

Sarah Mangle: Let’s start with you describing the zine.

Billy Starfield: Trauma Castle is a zine where I talk about some of my childhood experiences and my life now. It’s a per zine – a zine with personal stories and a couple of drawings and some collages, like most of my zines. I’m going to turn 30 this fall. The things I wrote about in Trauma Castle happened about 20 years ago.

SM: There’s a theme of time travel running through the zine. It’s powerful. There are moments in the writing where you explain the feelings you’re having simultaneously in the past and present, holding the big picture knowledge of the things you survived. There’s also a strong feeling of home running through the work. Your home now, separate from your family members, and your family members’ homes, and the memories that come with you.

BS: I feel that way too about it. Time travel rang a bell for me a few years ago when a friend told me, “Oh, yes, you’re talking about PTSD and some difficult stuff that happened, and it’s like we’re travelling in time.” And when my friend said that, I was like, “Yeah I totally feel like a time traveller.” The symptoms you experience when you have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, it’s kind of that.

SM: Do you have a relationship, when creating, between feeling emotional or physical pain and your art and writing? Is there a connection there for you?

BS: I have a weird relationship with pain, mostly because I’m a self-harmer. I talk about self-harm in Trauma Castle. I experience pain in different ways. In past years, I also experienced violence from other people. From people I loved, and from people I don’t really give a shit about. I have experienced police brutality. I believe in trauma pain. You know what I mean? Sometimes I feel weird pains in my body, pains I didn’t really feel before, that I think are related to all of that.

SM: That makes sense to me. Because of their specificity and the difficulties of the stories in Trauma Castle, they are special. It’s a gift to share them.

BS: I have a P.O. Box and people often write me letters about my zines. A couple of teenagers wrote to me about Trauma Castle. I wonder what my life would have been like if I had read stories like that when I was fifteen, instead of being older when I started to really get into zines.

SM: Because of your graffiti, your buttons, and your stickers, you’ve really pushed against masc gender presentations dominating the representation of being queer.

BS: [Laughs]

SM: Really! You’ve pushed, arguing for feminine visibility. I don’t know if the word “feminine” or “femme” is the right word for it, but against the centralization of an androgynous masc character being every queer character we ever see, especially in a queer, “lesbian”-esque scene. That visibility has pushed other people; it’s affected other people’s fashion, their gender identities, the arguments they’re having with people, the whole internet culture. You’ve been a huge influence in that way, and I wanted to talk about that because it’s been really important.

BS: I read an interview a few days ago where someone said that my work was influential to them. I inspired them to show being femme, specific colours, and specific aesthetics, specific kinds of femininity. I’m not too sure if I want to label my work as such or not, but anyway, it was really special to read that because I like their work and I think it’s super important. They were posing in front of my graffiti pieces and the interviewer asked them, “Why did you choose that specific place to take your picture?” And I was like, “Oh my God!” This is so special. I don’t really like wearing dark colours. I like things that are soft on the eyes. I see myself as non-binary and, for me, I don’t really feel the push to change the way I look, but I know it’s really healing for other people. I’m trying to feel good with my own body with the resources I currently have. I don’t feel swell about it all the time, but I like my body. It’s been mostly working.

As Billy says in Trauma Castle: “I am my very own best friend, my very own partner, let me treat myself right. All the best food and beautiful flowers. Smell it. Centering myself as the priority in my own life. Clothes that are comfortable, that only I think look flattering on me. Long baths drinking tea, reading sad books. Hours in bed with my magic wand. Private moment with myself where I learn about love and trusting my body.” mRb

0 Comments