Not long ago, a colleague complained to me that too much of Canadian drama nowadays consists of inward-looking “theatrical selfies.” Three newly published play texts, Trench Patterns, Shorelines, and Blackout go a long way towards mitigating that criticism. Each of the plays directs its gaze outward to tackle, respectively, the human cost of the “war on terror,” the terrifyingly imminent consequences of climate change, and the reverberations of the 1969 “George Williams Affair,” a race riot that took place on the ninth-floor computer department of what was then Sir George Williams University, now Concordia.

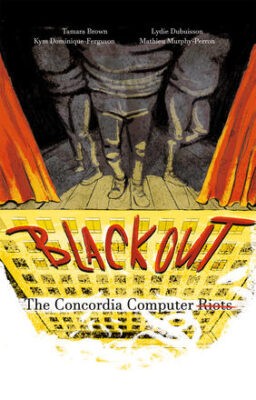

Blackout

The Concordia Computer Riots

Tamara Brown, Kym Dominique-Ferguson, Lydie Dubuisson, and Mathieu Murphy-Perron

Playwrights Canada Press

$18.95

paper

142pp

9780369104168

The incident, then, began when students barricaded themselves in the university’s computer department. This was after months of allegations about a biology professor’s racism towards Caribbean students failed to result in any meaningful action. Indeed, three Black students had been criminally charged after their passionate advocacy was misrepresented as threatening behaviour. When a fire broke out – whoever started it remains a mystery, but there’s no ambiguity about members of the public screaming “Let the n—s burn!” – the riot police moved in, resulting in multiple arrests and injuries, including one fatality, 18-year-old Coralee Hutchison.

Blackout is a corrective of sorts to a previous play on the subject, The Great White Computer, which caused its own incident back in 1970 when protestors invaded the Centaur Theatre stage, taking issue with white artists tackling black issues. This time, although one of the writers, Murphy-Perron (director of Tableau D’Hôte, the company that produced Blackout) is white, most of the creative team and all of the cast are BIPOC artists.

The result is a lively mix of realist drama, spoken word poetry, Greek Chorus-like descriptions, Shakespearean pastiche, and fist-in-the-air sloganeering. One meta moment sees the actors stepping out from their roles to directly address the personal pain felt during the creative process (we can definitely give a pass for that selfie moment), pointing out instances of present-day instances of racism in Canada. There’s also a nod back to Marie-Joseph Angélique, the 18th-century slave who allegedly burned down Montreal’s Old Port and was the subject of a previous Tableau D’Hôte production.

In a play that argues so passionately against dehumanization, it feels slightly uncomfortable to see police described as “pigs” who “can’t see further than their snouts,” while one professor is dubbed a “devil,” following his allegorizations about DNA and RNA, more in line with Nazi-style eugenics than the laboratory of a nominally equitable university. I’d guess, though, that these monologues are more creative license on the part of the writers than anything the prof in question actually said or wrote. But racism, of course, is directed at what people are, and the aforementioned insults are directed at what people do. In the case of that professor, what he did was downgrade the Black students’ results relative to their white classmates, a practice that is irrefutably proven when the students engineer an experiment.

Shorelines

Mishka Lavigne

Playwrights Canada Press

$18.95

paper

106pp

9780369104618

Shorelines, the latest play by two-time Governor General Award winner Mishka Lavigne, was also to have been a Tableau D’Hôte production, with a planned 2021 premiere atop a multi-storey in Verdun. Alas, the production was cancelled during the pandemic (it later debuted as a production by Ottawa’s LabO). Though the pandemic wasn’t the reason for the cancellation, it would have made for a grimly apposite backdrop, given the play posits a near-future in which society ceases to function, here because of climate change.

Alix and Evan are seventeen-year-old twins eking out a precarious existence in a disused swimming pool as the sea catastrophically reclaims the land and much of civilization. Their father has been missing since he went foraging in one of the submerged highrises, and their grandmother, a once-celebrated science journalist, is now succumbing to the mental erosion of dementia. Meanwhile, Portia, a heartlessly pragmatic politician, leaves the security of the military zone for reasons that eventually knit all four characters together.

Speculative dystopias can make for ponderous drama, and Shorelines certainly doesn’t leave much room for humour in its grim foreboding of our future. But Lavigne has a knack for creating arresting word pictures out of a series of first-person arias. If this results in a drama that largely tells rather than shows, it nevertheless builds powerfully towards a thriller-like climax in which human incompetence allies with centuries of heedless exploitation to deliver an overwhelming coup de grâce.

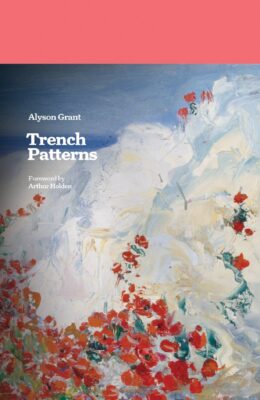

Trench Patterns

Alyson Grant

InfiniPRESS

$15.00

paper

120pp

9781777873547

It’s a powerful hospital-set drama in which Jacqueline, a Canadian army captain, attempts to put her shattered mind and body back together after a traumatizing event in Afghanistan. Sessions with a well-meaning but out-of-his depth psychiatrist are interspersed with ghostly visitations by Jacqueline’s great-grandfather, Jacques, who was executed during the First World War.

Although taking in world-shattering events from across three continents, Trench Patterns is very much a Montreal play. We learn that Jacques, a working-class francophone, had a doomed romance with a Westmount Anglo. More disturbingly, the play also addresses the brutal treatment and higher execution rate of French-Canadian and Irish soldiers in the trenches.

Grant’s play elegantly braids together the two historical periods as Jacqueline attempts to cope, often with mordant humour, with the ghosts of her immediate history and the distant past. As well as photos of the original production, this edition also includes an eloquent foreword from fellow playwright Arthur Holden in which he meditates on the play’s title – named after a thesis the main character wrote on the counterintuitive complexity of strategic defences – as it pertains to the moral paradox of lethal force being leveraged to do the right thing. Ten years after the play was produced, Afghanistan has again fallen to the Taliban, leaving Grant’s trench patterns of the mind even more tricky to negotiate.

As with the other two socially and politically engaged playtexts covered here, Trench Patterns reminds us that the past is prelude to present quandaries – and, if we’re not heedful, future nightmares.mRb

0 Comments