In the title story of Josip Novakovich’s new collection, a Croatian immigrant, near-indigent after failing to secure expected seasonal employment, hitches a ride with a drunk driver in the American Midwest, gets drunk himself, and winds up in a small-town jail. If this is an allegory for the immigrant experience in contemporary America, with the titular weed serving as a metaphor for the transplant who can’t quite find purchase in new soil, the image it calls to mind looks a lot closer to a scowling Donald Trump than to the Statue of Liberty.

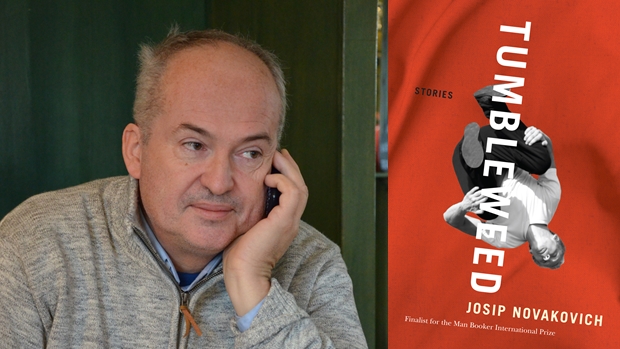

The prolific Novakovich, a Montreal resident and professor of creative writing at Concordia University, left his native Croatia in 1976 and had a lengthy odyssey through American academia, garnering multiple literary accolades before moving to Canada in 2009. His profile was given a considerable boost in 2013 when he was named a Man Booker International Prize finalist; the honour brought added attention to 2015’s Ex-Yu, a stylistically varied collection unified by the common thread of war and exile.

Tumbleweed at first appears to be a logical continuation: when an introductory vignette set in Belgrade is followed by the story described above, it seems we’re in for another collection of finely wrought tales spinning variations on what is probably the central theme in contemporary world literature. But then, quite unexpectedly, comes a long sequence of stories, broken up by a few interstitial bits of autofiction, where the focus is on animals: a rat in a squalid New York apartment shared by music students in “Strings”; another rat in another home, this one granted a first-person voice in “My Hairs Stood Up”; an unspayed rural troublemaking cat in “Byeli: The Definitive Biography of a Nebraskan Tomcat”; a cat named for a Soviet dictator in “Stalin’s Perspective”; a far-ranging farm dog in “Son of a Gun”; a ram named for a head-butting soccer immortal in “Zidane the Ram”; and an orphaned kitten saved from the streets of St. Petersburg in “A Cat Named Sobaka.”

Tumbleweed

Josip Novakovich

Esplande Books

$19.95

paper

212pp

9781550654516

“They tell us about us,” says Novakovich in a Laurier Avenue café near his Plateau home. The subject is animals and their profusion in Tumbleweed. “They’re a mirror for humans. How we treat animals tells us a lot about what kind of people we are. I also think animals have adventurous lives. If you really follow what an animal does, you’ll have a lot of stories to tell. I’m in favour of total freedom, and when I was living in some of these isolated settings I couldn’t have it, but my animals could. They were living my dream in a way. We live such sublimated, unspontaneous lives, so it’s admirable to see an alternative – something that is actually in us, after all. We’re all animals inside.”

It should be pointed out that the menagerie thins out a bit toward the end of the collection. “Crossbar,” about the aftermath of a hotly contested soccer match in Zagreb, is a study in the pathology of sports fandom that’s all the more effective for having been written by an actual sports fan. Until the scene that involves a beheading, it actually had me thinking it might be a true story. (And even here animals play a part, in this case two bears in a zoo.)

The closing story, “Café Sarajevo,” named for the now-defunct establishment in Montreal’s Petite-Patrie, is an affecting retelling of an encounter with a fellow émigré, a man who had remained in Sarajevo throughout the siege despite being a Serb, and who now suffers a form of PTSD, walking the streets of his new city eight hours or more every day because he can’t stand confinement. The image of two former Yugoslavians being unsure of the other’s ethnicity is a poignant one. “It’s kind of symbolic that there was a Café Sarajevo here and now there is just its ghost,” said Novakovich. “There also used to be a Serbian café. A couple of Slovenian delis still exist, but in general there aren’t enough people from the former Yugoslavia to maintain an ethnic business like that.”

As an established writer with a growing profile, does Novakovich ever feel himself perceived as a putative spokesperson for Croatians in North America? “During the war, maybe,” he tells me, “when I was in the States and Croatia was in real trouble and really did need people speaking for it. NPR once called me, but they didn’t call me back. Esquire was going to send me to write a story, but they ended up sending a Brit, I think because they were concerned that they were going to get a biased view. There was a lot of that at the time – people deciding they would rather have unbiased ignorance than biased knowledge on the subject.”

For Novakovich, having what amounts to a pre-sold readership, even if it’s not a huge one, comes with advantages and disadvantages. “Publishers always ask ‘What’s your platform?’ and if you have an ethnic audience, that’s a plus,” he said. “But I don’t always get along with the community. Promoting Ex-Yu in Toronto didn’t turn out well. I was asked to do a talk as well as a reading, and in that talk I quoted (Samuel) Johnson saying, ‘Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.’ As far as I’m concerned, first be a good human, then be good at what you do, then worry about the other stuff. The best Croatian is someone who’s a bad Croatian. They didn’t like that. I sold six books before the speech, and none after.”

Novakovich has written relatively little fiction set in his adopted country, but says that may well change: “Sometimes it takes years before you feel you are ready.” In the meantime, he’s keeping up his exemplary pace. Not long after we met he was due to leave for a six-week writing retreat in Bulgaria, where four of his books have been translated; while there he’ll be making side trips to some old Croatian haunts and doing revisions on an almost-finished novel set in Putin’s Russia. But for all his international interests, he’s looking settled in Montreal: he obtained Canadian citizenship three years ago and even wrote a book of essays, Shopping for a Better Country, about the process. Choosing against our southern neighbour may not have been easy at the time, but it’s a decision he doesn’t regret. “Trump has made Canada great again. If I had any doubts about being here, they’ve been lessened.”

0 Comments