You know the story – the one where a woman writer’s words or ideas are ascribed to the man of the house? He gathers up all the glory while she dutifully disappears into history’s margins, too busy darning his socks or transcribing his manuscripts for any of that fancy-pants fame? Sadly familiar, such stories needn’t end like this…

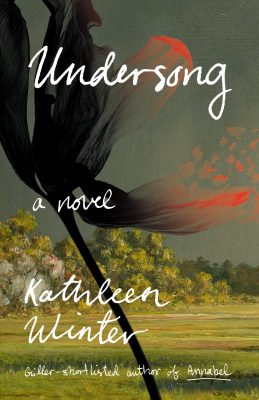

Kathleen Winter’s ravishing reimagining of Dorothy Wordsworth, sister of celebrated English Romantic poet William Wordsworth, makes an old story new. Addressing a collective wound – gender inequality – Undersong glistens with healing potential and drop-dead gorgeous poetry.

In this knockout novel, we get to know Dorothy as the wildly perceptive writer that she was, indispensable to her brother’s success, as he drew inspiration from her diaries, and strongly influential on Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Refreshingly, Winter’s fictionalized yet convincing account also challenges a common conclusion: that Dorothy, unpublished within her lifetime, was perfectly content to crouch in William’s shadow.

Undersong

Kathleen Winter

Alfred A. Knopf Canada

$32.00

cloth

320pp

9780735278226

While underscoring the plight of the working class, sensitive Dixon provides a captivating close-up of the Wordsworth family, along with glimpses of their illustrious network, including William Blake, Thomas de Quincey, and Mary and Charles Lamb. Meanwhile, UK-born Montrealer Kathleen Winter seems right at home in nineteenth-century England, her dialogue flush with antique vernacular and spellings. “Aye, I’ll read ye the red diary now, today, before we leave, ye and me,” Dixon promises the hardworking garden bees he so admires for their loyalty to their queen.

Dixon talks to the bees about his own queen, Dorothy (in his mind, named “Rotha” after the river), to keep her essence alive. “Tell the bees about your Rotha, who looked inside ten thousand star-chambers – bluebell, potato-flower – and saw each mote as a bee does, each ray or spear or flare shaking,” encourages Sycamore.

The bees, like Sycamore, are endowed with otherworldly wisdom, and passages that highlight their knowing feel all the more poignant in the context of today’s declining wild bee populations. “The bees sense in every bluebell the myriad ways humans may destroy their haunts,” says Sycamore.

Echoing this forecast, Rotha documents the “stench & racket from industry & progress” in the book’s sixth and final section. Winter’s poetic prowess, staggering throughout, is only more potent in these closing pages, devoted to fictionalized Dorothy’s private journal. This feral finale taps the suppressed rage that can ravage the bodies of women who, for reasons of safety or practicality, feel forced to play small (a plausible contributor to some of real-life Dorothy’s ills). “I held myself back from my own body – of published work,” the heroine laments. In private, Rotha’s innate wilderness lets loose; as though breaking a dam, her river-like voice rushes forth with fierce, uncompromising beauty, confronting the culture’s blindness towards aging women especially, while revelling in the kind of vision that women themselves gain with time: “Yes our bodies are covered in sensitive eyes.”

Until the very end, second-sighted Dorothy is in her element outdoors, where she embodies and voices the wild wisdom her world wants to tame, both in nature and in women. And through her eloquent, deeply empathic revival of this under-acknowledged nature writer, Winter lends an ear to the sentient natural world, “the undersong of the leaves and the birds,” more moving than ever today as Earth’s ecosystems rapidly decline, overstressed by unsustainable industries – another story that needn’t end like this…mRb

0 Comments