Us Conductors is the debut novel by Sean Michaels, a Montreal-based author who founded the popular music blog Said the Gramophone. It’s a fictionalized story of Lev Termen, the Russian engineer, physicist, and inventor of the theremin – the musical instrument whose pitch and volume is controlled by the proximity of the player’s hands to two antennas. But, as Michaels puts it in the author’s notes, the story “is full of distortions, elisions, omissions, and lies.”

The story, told from Termen’s first-person point of view, has two parts. The first of these takes place in 1938 while Termen is on The Stary Bolshevik ship back to Russia after having spent eleven years in New York City. In it, he recounts his student days in Russia, moving to America to introduce the theremin to a new audience, and selling his other inventions to American investors. This takes place against a backdrop of the Wall Street crash, Prohibition, and the Jazz Age. In New York City, he meets Clara, a violinist and, under his tutelage, a budding theremin virtuoso.

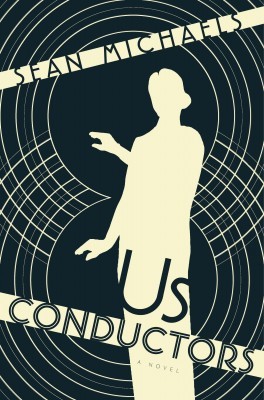

Us Conductors

Sean Michaels

Random House Canada

$22.95

paper

368pp

9780345813329

The second part, which is much stronger (it is where the interesting characters can be found), takes place eight years later. Termen is in Marenko prison, outside Moscow, describing the remarkable events that followed his return to Russia, including some time in a Siberian Gulag. The writing is minimal and punchy, and has a philosophical sensibility, enabling the suspense to neatly unfold: “We wrapped our rags closer, for warmth, trying to add months to our lives.” It viscerally recreates the violence and suffering in a Gulag camp.

The novel is addressed to Clara (via the pronoun “you”) as if Termen were making a declaration of love. Unfortunately, there is a jarring conflict between his descriptions of New York: some detailed descriptions create the illusion of a mock present tense for the reader, while others – told in retrospect from the ship/prison – are glossed over. Termen goes from intensely remembering pointless and impersonal details, as if Clara had total amnesia (which she doesn’t), to expressions like, “Before long it was another year.” The result is that it doesn’t feel like love. Rather, it feels like it wasn’t really written for her, which undermines the story greatly. Regrettably, the authorial solution to the problem fixes this structural flaw very late in the book, at page 272: “Sometimes I am writing you a letter, Clara, and other times I am just writing, pushing type into paper, making something of my years.”

Furthermore, instead of creating a particular way of seeing, efforts to integrate a scientific sensibility into Termen’s thought-stream don’t go very far and remain superficial: “My mind and hands were following the directives of my wakeful loosened heart and I was solitary, moving, a free particle that spins, that feels the weak and the strong forces exerting gravity upon it.”

Termen’s life is indeed remarkable, but, in this version of it, you have to read 200 pages before it becomes engaging. At that point it’s very engaging. mRb

0 Comments