“The business of fiction is to probe the tender spots of an imperfect world,” writes Barbara Kingsolver in her essay “What Good Is a Story?” Not only does this sentence sing (read it aloud), but it also makes the important point that fiction is serious business. To recognize life’s tender spots and extract the meaty stuff is the mark of a skilled writer. Unfortunately, Elizabeth Bass, who in Wherever Grace is Needed tackles the complexities of family, its bonds – real or imagined – and the ache to belong, fails to find these tender spots. Her efforts flounder with characters stuck at surface level and a story that fails to enlighten.

Grace Oliver’s parents divorce when she is still a little girl growing up in Austin, Texas. Grace’s mother moves her to Portland, Oregon, separating Grace from her father and two older brothers. Twenty odd years later, a thirtysomething Grace owns her own business, is in a committed relationship, and is working hard to stay grounded.

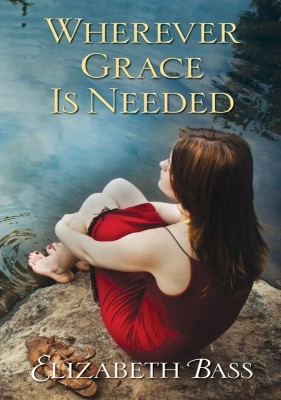

Wherever Grace Is Needed

Elizabeth Bass

Kensington Books

$17.95

Paper

393pp

9780758265944

When one of her older brothers calls to say that their father has been hit by a car and has broken his leg, Grace volunteers to put her life on hold in order to nurse him back to health. The move back to Austin forces Grace to confront her feelings of detachment from the family she had left as a child. While she’s there, her father is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and begins a steady decline.

The book is split between two stories – that of Grace Oliver and that of the West family, neighbours of Grace’s father, consisting of a widower and his three children who recently lost their mother and sister in a car accident. Readers hop between Grace’s search for belonging and the West family’s journey through grief. The bridge is Grace herself, whose relationship with the West family is what finally helps her put her own life into perspective. The subject matter is rich but Bass fails to infuse her characters with more than stereotypes and clichés. During moments of emotional tension, Bass holds the reader’s hand, not trusting us to make connections. An example is a scene later in the book with widower Ray West and Grace. Emboldened by recent talks with Grace over the backyard fence, Ray decides to throw a neighbourhood cookout in the hope that it will repair the damage he’s done to his surviving children and let the neighbourhood know he’s on the mend. The day before, he goes over to Grace’s house looking for a phone number, but ends up confessing his love for her in her living room.

He tugged her hand and she seemed to slide right toward him … Their lips met and she was amazed by the hunger she sensed in him in just a brief kiss. He held her tight, almost like a man hugging a life buoy, until she pushed away … he was studying her face as if he’d never really noticed it before. “I half suspect I could fall in love with you, Grace.”

Aside from the tacky dialogue and glar ing similes, the real disappointment is the title of the next chapter: “Things Fall Apart,” in which Ray’s BBQ is rained out and his daughters get into a scratching match. The author of more than thirty romance and “women’s fiction” novels, Bass fails to penetrate into deeper emotional realms. This is not to say there is no potential for depth. The final scene deals with a photograph of the surviving West girls as small children, playing together in a happier time. The death of their mother and sister has completely destroyed their relationship, but the photo gives them a way to reconnect without words. Bass finally seems to discover one of life’s tender spots, but doesn’t manage to probe it. mRb

0 Comments