Virginia Pésémapéo Bordeleau’s newest novel Winter Child draws embodied affect from the reader like poetry, and is so deeply personal that it almost reads like creative non-fiction. Pésémapéo Bordeleau’s words aren’t obscured by smoke or mirrors; instead, she depicts a complex constellation of relations among three generations of a Cree-Métis family, and all its present love and strain. Susan Ouriou and Christelle Morelli’s translation of the French original blends romantic turns of phrase with the transformative storytelling power of Pésémapéo Bordeleau’s Cree and Métis ancestors. Winter Child is comprised of several short narratives, often no more than two or three pages in length. Each short narrative represents a single memory told from the perspective of the narrator, who we know only as “the mother.” The narratives potently describe seemingly mundane everyday activities, finding love and teachings within the beautiful, and at times traumatic, present of our lives. As everything does, the book begins with the birth of a child – the mother’s son.

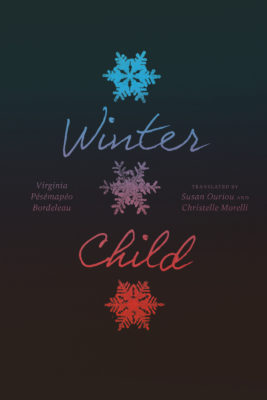

Winter Child

Virginia Pésémapéo Bordeleau

Translated by Susan Ouriou and Christelle Morelli

Freehand Books

$21.95

paper

168pp

9781988298061

Several of the narratives in Winter Child follow the life and unexpected death of the mother’s son. We are a fly on the wall as the mother remembers her son’s youth. We witness his bafflement at the Euro-American gender binary, and a young Indigenous child’s incomprehension of gendered rules of dress. We witness his awe at the beauty of feasting and the ceremony alive in the community around him, which is marred by alcoholism and colonial affect, and his first sip of liquor, given to him by his grandfather. The mother recalls, “That drink, the effect it had and its taste, would never leave him.” A penchant for excess and a fire for life that his mother could not wane would cause his departure from this world.

Winter Child is a collection of narratives about complex relationality, death, loss, and moving through grief, despite it all. Though the mother has experienced unspeakable abuse and trauma, she continues, and with love to boot. Pésémapéo Bordeleau has woven together an exercise in sitting with and moving through pain, beautifully illustrating that – yes – there is beauty in the struggle. Because I cannot say it as poignantly as Pésémapéo Bordeleau, I will leave you with her words and a perfect summation of the mother’s journey: “Cry with me, lean your sky against my forehead, gather the angels around us. Tell me that the earth is beautiful, that the horizon has a place for me. Your phantom fingers float over the strings of your soundless guitar; tell me I owe it to myself to live and that all music hasn’t died with you.” mRb

0 Comments