The fathers of literature bookend the scale of status and influence, from Atticus to, say, Humbert Humbert; most fall in between, flawed and inescapable.

Readers familiar with Heather O’Neill’s work, particularly her breakout novel Lullabies for Little Criminals, will have encountered her bad-but-beloved dad: purveyor of some necessities and more shouldn’t-haves, dispenser of dubiously valuable advice, and default moral pivot whose habits and hangers-on, if they don’t wind up getting La Protagonista killed, will surely end up making her stronger.

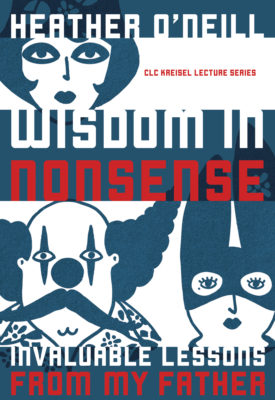

Wisdom in Nonsense, which is based on the CLC Kreisel Lecture O’Neill gave in 2017, introduces The Real Mister O’Neill. Having aspired to become a gangster in his youth, Buddy O’Neill stepped up to the paternal plate after his once-and-former love shrugged off the yoke of motherhood. In these thirteen “lessons” (and one incongruous blank-paged invitation for readers to contribute their own dadnecdotes), O’Neill fille catalogues what good can be gleaned from advice that is at worst delusional and at best out of step with reality.

Wisdom in Nonsense

Invaluable Lessons from My Father

Heather O’Neill

University of Alberta Press

$11.95

paper

64pp

97817721237777

The book is short and, as befits a public address, chatty and accessible. O’Neill’s apparently extemporaneous looseness is recognizable in the cascading clauses that locate the banal before imbuing it with the implausible and, often, the undermined sublime: “The only things that were strange or modern,” she remembers of an eccentric friend, “were all the Pepsi bottles that filled up the backyard”:

There were hundreds of them back there. One night when it hailed, the noise of the ice pellets on the bottles played Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. But only the back cats were there to testify.

The specificity – the Pepsi, the Stravinsky, the black cats – is vivid, without writing the whole film on our behalf. But what makes the writing vintage O’Neill are her trademark zingers. She manages to toss out snippets that slice through the human condition, at once deadpan and dead on: “When men who are over fifty and have nothing to show for their efforts begin to feel sorry for themselves, mayhem ensues.”

Wisdom in Nonsense is also, for an author whose style might be dubbed confessional mythologizing, surprisingly unadorned. Alongside discourses on the value of petty theft and whether “being betrayed was better than being alone” are commonplace disappointments of childhood (dejected at not being chosen to play the tuba, O’Neill instead became a soulful trumpeter) and writerly origin stories (how happening upon Anne of Green Gables sparked a lifetime of ravenous reading).

And it is the testimonial of a daughter, her anger cloaked in wit, for her imperfect father. For instance, so abhorred was Paul Newman in the O’Neill household that the standard toast was, “Not to Paul Newman.” As throughout the book, “Never Watch a Paul Newman Movie” has the sheen of an eye-roll, but there is vulnerability there too. After she inadvertently sees Old Blue Eyes on the screen, O’Neill succumbs to his charms. Yet – “I have still, however, never tried his salad dressing out of respect for my father.” Blood is stronger than at least vinaigrette.mRb

0 Comments