First let’s address that rather grandiose word in the subtitle.

No, Adam Leith Gollner and his publisher are not suggesting that Dany Laferrière will live forever. What they’re doing is referring, in a fittingly playful way, to the ultra-exclusive Académie française and their 2015 induction of Laferrière. The first Quebecer thus honoured is now, as per the standard (and perhaps a tad hubristic) citation, among “les immortels.” More than a handy word for a book cover, it’s a salutary reminder, for those might be tempted to take him for granted, of just how far the Montreal writer born in Petit-Gouâve, Haiti, has come.

This new undertaking by QWF Award- winner Gollner belongs to a specialized category attached to writers with especially fervent followings. Can there be a devoted reader who hasn’t mused on how fun it would be to hang with her favourite writer for a couple of hours? Not that an interview book is always a predictable thing: a writer’s everyday mode of spoken communication won’t necessarily jibe with the page-voice we’ve come to know. Often enough, in this reviewer’s experience of interviewing writers, there’s little discernible overlap at all, nor need there be. Here, though, you’ll find no such disjunct. If you’re a Laferrière adept, you can dive into Working in the Bathtub with full confidence; if you’re not, this book may well make you one.

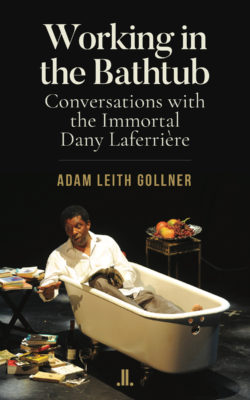

Working in the Bathtub

Conversations with the Immortal Dany Laferrière

Adam Leith Gollner

Linda Leith Publishing

$18.95

paper

148pp

9781773900735

In these pages, such counterintuitive aperçus just keep on coming. No matter the subject, it seems Laferrière can find an original way in, be it the complicated art-and-commerce relationship (“If Basquiat hadn’t been able to sell his paintings, he’d still be alive”), putting his roots to proud use in his work (“I’ve always found it strange that writers thank people in their acknowledgements. I put that into the interior of my books”), the writer as public crusader (“For me, a writer who engages politically is a writer who doubts their own talent”), coffee (“[In Haiti] you need to wait until around the age of nine before they’ll give you grown-up strength coffee”), menial labour (“I had a really hard job in Valleyfield making rugs out of cows”), the value of laziness, writing in bathtubs, and on and on. Pull quotes? It’s like one big pull quote.

Loquacious as his interviewee may be, what Gollner achieves with these conversations is nowhere near as easy as it might look. Firm in his steering of the proceedings, he is still loose enough to respect the natural rhythms of a true conversation; he knows when to keep things ticking and when to let it get discursive and go down byways, many of which would have made for a fine main route. This reviewer, for one, would be first in line for a whole book of Laferrière and Gollner talking about V.S. Naipaul. Hint, hint… mRb

0 Comments