The Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region is scenic; the food is delicious, and the culture is deep and open to visitors. But when a small town is your hometown, there’s such a thing as too quaint – and the dark side of tight-knit communities is almost invariably, proverbially suffocation.

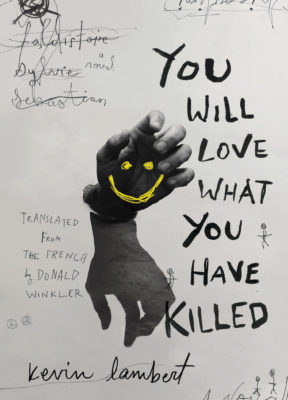

The dark side of Chicoutimi, an industrial town in the Saguenay, is the main character in Kevin Lambert’s first novel, recently translated into English by Donald Winkler as You Will Love What You Have Killed. Lambert, a Chicoute native, channels the resentment that fuelled his flight to Montreal in early adulthood into this vengeful, desperately violent novel. The autofictional narrator, Faldistoire, nurses the bitterness of entrenched homophobia and secret love, of family secrets and rapey ancestors, of social status and the crimes it can forgive. Faldistoire recounts his childhood and adolescence as a misfit in a small town where fitting in, if not a prerequisite, certainly makes life easier: go along, don’t be different, don’t rock the boat. But Faldistoire, gay and defiant, refuses to bend.

The collective cost of fitting in, and the individual pretense of happy homogeneity, is a society that eats its young – fairly literally. The narrative premise of the book is the serial deaths of local children, in physically horrific more-or-less accidents. A little girl playing in a snowbank is shredded by a snowblower; a boy gets a pencil shoved in his skull; a father nudges his son into the cougar pit at the Saint-Félicien zoo; a respected former school principal asphyxiates his four-year-old grandson after he tries to force the child to fellate him; a father slaughters his wife and children.

You Will Love What You Have Killed

Kevin Lambert

Translated by Donald Winkler

Biblioasis

$19.95

paper

188pp

9781771963527

The book is willfully unpleasant, but unsensationalistically so. Death is everywhere, and its physical presence hangs over the whole town like a repetitive macabre anthem: a mother hangs herself, a loser strides into a circular saw, a trans woman splits apart in childbirth. Croustine, the boy who gets eaten by cougars, wears his taxidermied poodle as slippers. Though rife with violence and body-count headlines, the novel manages to make each of the fatalities that feed the narrator’s rage vivid, individuated, and moving. The impact and reach of Lambert’s writing is in part the result of old-fashioned narrative mastery: the deaths are for the most part amply foreshadowed, and the town is carefully set up in a kind of misanthropy gothic. With each act of violence, the reader is appalled – and appalled at not being surprised – and Lambert deftly has us hooked as the whole wreck painfully unfolds.

Chicoutimi’s greatest sin, in You Will Love What You Have Killed, is its deeply invested facade. Everyone pretends not to know that Paule used to be Paul; the resident witch is arrested even as her business booms; the guys at the strip bar obliviously cheer on the high-school student shimmying before them. In a town where ghosts and sex are shushed, the historical and personal erasures are manifested in language, the only locus of control. There are

no words in this vocabulary that tells the truth about our earth chock full of dead bodies, whose slimy soil has been oozing death since the world began, where you can no longer push in a shovel without extracting some human scrap, some corpse from some slaughter of some unremembered genocide.

It’s clear that the author’s retribution will be the written word from the very first chapter, when Faldistoire shoves a marker into the pencil sharpener. “The ink will spurt,” he warns, and so Kevin Lambert lets loose his pen. mRb

0 Comments