When I taught creative writing to people with schizophrenia in New York City, they often came to workshop wearing earphones. Many listened to music while they wrote. Hearing voices – often accusatory and threatening – is a hallmark of this devastating mental illness, and listening to music, my students told me, helped to drown out the dissonance in their heads. In her absorbing and warm-hearted debut novel, A Secret Music, Susan Doherty Hannaford braids these fascinating subjects – music and madness – into a poignant family story.

In early spring, I met up with Doherty Hannaford in her sunlit Westmount home, about a dozen blocks west from the setting of A Secret Music on Fort and Dorchester (now René-Lévesque). She served cappuccinos as we chatted for several hours, warming our bones after yet another ferocious winter.

The novel is inspired by the author’s father who never spoke much about his painful but fascinating life, growing up with a mentally ill mother. When Doherty Hannaford’s daughter interviewed him for a high school biography project, he finally shared the rich details of his life – just in time. Shortly afterward, he passed away. “I was meant to carry his story forward,” Doherty Hannaford tells me. In fact, he entered her dreams so often that she realized he was directing her project and keeping her positive through countless rewrites. “In his last appearance, he was fourth row centre in an auditorium, as if to say, ‘Let the show begin.’”

A Secret Music takes place in Montreal in 1937 with the Great Depression still devastating Canada. CBC radio is in its infancy, Benny Goodman is the reigning king of swing, and teenage prodigy Lawrence Nolan is pursuing his dream of becoming a concert pianist. He decides on his calling at age six, memorizing an entire book of piano pieces to make his pregnant mother smile. As a reward, she takes him to Archambault to buy new sheet music, and on one of the store’s pianos, Lawrence plays an impromptu allegro by Mozart. In the taxi home, his mother takes his hand and murmurs, “Lawrence, today I heard a genius.” He feels an electrical current between them and later whispers to her, “When I play, I play for you.”

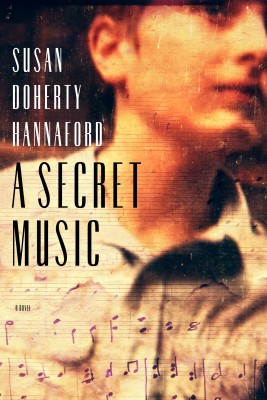

A Secret Music

Susan Doherty Hannaford

Cormorant Books

$21.95

paper

296pp

978-1-77086-367-5

The emotional core of A Secret Music is this passionate, enmeshed bond between mother and son, both of whom hope that his music will help keep her demons at bay. For Lawrence, his mother’s belief in, and single-minded focus on, his music is a burden-laden blessing. The layers and complexity of their relationship bring to mind another intricately merged mother and son duo, Paul and Gertrude Morel, in one of my favourite classic novels, D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. No accident, perhaps, that Doherty Hannaford named her hero Lawrence, not only after her father, but also this literary master.

While providing a refuge from the chaos of his mother’s madness, music offers the truest, deepest way of loving her and of being loved in return. In a wonderful scene when Christine is well, the two play a duet by Camille Saint-Saëns. It’s a magical moment, both for Lawrence and the reader. “Playing together meant he and his mother could share a sacred space”; she radiated a bliss and generosity that “filled him up.”

Doherty Hannaford’s portrayal of Christine’s struggle with mental illness is deft and subtle as Christine cycles between windows of reasonable normalcy and spells of psychosis, between illuminations and darknesses. We perceive her through Lawrence’s eyes, rather than through dehumanizing diagnostic labels. When she is ill, she puts her young baby into a dresser drawer, vows love to Franz Schubert, claims her hands “aren’t my hands,” strips off her clothes to “Auld Lang Syne,” hibernates in bed, or is taken “away.” During welcomed remissions, she is fragrant with Evening in Paris and a whiff of cherry cookies, impeccably dressed, and articulate.

Twenty percent of Canadians will experience a mental illness at some time during their lives, according to the Canadian Mental Health Association. Doherty Hannaford tells me that severe mental illness has touched the lives of several of her loved ones. She also volunteers at the Douglas Institute, working with people with schizophrenia, taking them out for coffee, a walk on the mountain, or a shopping trip to Winners, introducing “a dose of normalcy.” The novel dramatizes the rondo of shame, blame, and pain that people with mental illness and their families face every day. While there is no shame in having cancer, mental illness carries great stigma. Christine’s illness is kept hush-hush, the family certain that they will become social outcasts if their struggle comes to light, secrecy only adding to anguish.

One of the joys of reading this novel is an immersion in music. No surprise that Doherty Hannaford studied piano and is passionate about classical music. For the sonorous details, such as the rigors involved in becoming a top tier performer, she interviewed concert pianists and instructors, as well as students and faculty at the Glenn Gould School in Toronto.

Doherty Hannaford wrote much of the novel at the Westmount Library, poring over streetcar maps and Lovell’s Directory of 1937 to get specific addresses key to the story just right. “I loved that part of the process,” she says. “Suddenly, it’s dark outside and I’m still reading about milkshake flavours and what this treat cost back then.”

“My biggest challenge was structure,” Doherty Hannaford confides. “My story got too big.” She put major scenes on recipe cards, so that she could reimagine them and their sequence. Later, her editor, Marc Côté, helped her to cut over a hundred pages, a tough process that no doubt strengthened the book.

Though most of the writing in A Secret Music is supple and fine, Miss Tarasova, Lawrence’s dedicated piano teacher and a Russian émigré, is intermittently diminished into caricature through speech conveyed in an exaggerated, but inconsistent dialect: “They vil make us a recording for our submission…. Don’t ask me any kvestions.” Yet elsewhere Miss Tarasova speaks eloquently about romantic music: “You must dream the piece when you play it…. If you don’t dream, the music is nothing but a rubble of notes.” Eschewing dialect and highlighting Miss Tarasova’s unique voice through phrasing and word choice would have worked better. That said, this is a small quibble for a book that works beautifully on so many levels.

A pleasure of A Secret Music is how fond we grow of nearly all of the characters, even the largely absent father who has made his way from humble, hardscrabble beginnings in Griffintown, processing inedible carcasses, to being the sole proprietor of an abattoir. Full disclosure: I cried at least once while reading this book and did not want to part with the Nolan family when I turned the last page. A Secret Music sings. mRb

0 Comments