Rawi Hage likes to think of himself as a historical novelist, but you wouldn’t know it from reading his new novel Carnival. Set in an unspecified time, in an unnamed city, it contains no historical figures or events. When first reading it, you might think it is many things – a paean to the imagination, a dark vision of urban alienation, a collection of wild stories experienced by a nocturnal taxi driver – but a historical novel probably isn’t one of them.

And yet, Hage explains, “we have to acknowledge the multiplicity of history.” Carnival might not have “that linear presentation of a historical book,” but every last character is dragging around the memory of certain historical events like so many cans behind a wedding car. “In a sense, this is where it becomes a Canadian novel,” Hage says. “More and more, part of Canadian history is the history of elsewhere. You have to talk about these histories. And there is one thing that is in common with all of these histories, and that is the violence.”

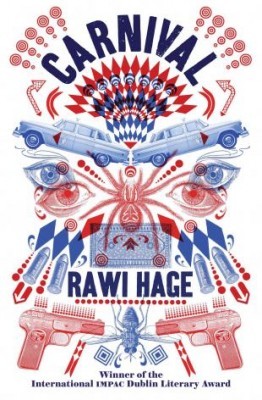

Carnival

Rawi Hage

House of Anansi Press

$29.95

cloth

289pp

978-0-88784-235-1

The book’s multiple storylines are told by Fly, a taxi driver who works the night shift in a city known for its carnival. He is a wanderer, one of those “operators who drive alone and around to pick up the wavers and the whistlers on edges of sidewalks and streets,” one of those drivers who “navigate the city, ceaseless and aimless, looking for raising arms to halt their flights, for the surfing lanterns to shine like faraway ships leaving potato famines and bringing newcomers.” Fly is part of a community that relies on the city’s carnival while staying on the margins, taking business from party-goers, but preferring to spend time away. They read in their rooms or drink under bridges.

Hage likes his narrators tough. As with Bassam in De Niro’s Game and the unnamed narrator in Cockroach, Fly is at once a poet and a brawler: even as he is beating someone up over an insult or an unpaid fare, his words are beautiful, his tone both lyrical and wry. By creating this dissonance between content and form, Hage infuses the life of this taxi driver with poignancy – we are caught between the disappointments that surround Fly and the crystalline language in which they are described. In a way, we are made to use Fly’s own coping mechanism: just as he temporarily loses himself in the volumes of his library, re-imagining history and creating his own fantasies, we sometimes lose ourselves in Hage’s richly imaged prose, only to be yanked back to earth by spare sentences such as these:

He sat at the kitchen table, and when I offered him some food, he asked for a glass of water. He pulled out some pills and swallowed them.

Talk, I said, and he told me the story of his incarceration. […] Otto was pushed out of his

chair. One police officer watched while the other beat him with his stick. After a while, the second officer came over and started kicking Otto and stomping on him.

As Hage explains, “the arc is not in the plot this time, it’s in the aesthetics,” which he links with “movement” and “contained chaos.” Fly’s friends, acquaintances, and customers flit through the novel, appearing out of the blue and then disappearing. Sometimes they reappear, sometimes they don’t. No matter how brief their cameo, though, Hage gives us a sliver of their private loneliness and the little things that keep them spiritually afloat. His deep empathy and his eye for the absurd make the novel at once hilarious and sad, tender and full of rage.

Be it a protester arrested and unjustly shut in a mental asylum, a journalist threatened because he comes from a country responsible for colonial atrocities committed before his lifetime, the neglected son of a prostitute or her Angolan pimp, every character feels as if history has robbed them of something. As a drug dealer says when Fly asks him whether the requested errand is legal: “What’s legal, my man? What is? Is history legal, was Vietnam legal. What the fuck is legal in this universe? Stars eat each other, wolves eat the pigs, and Grandma fucks over Little Red Riding Hood.”

Even the spoiled tourists whom Fly chauffeurs around feel that the carnival city has dealt them a bad hand. The same goes for the strippers, the clowns, the born-again Christians, and the drag performers who all get into Fly’s car, along with the motley crew of drivers who hang out in Café Bolero, waiting for a call from the dispatcher.

For a few years in Montreal, Hage was himself a taxi driver yearning for a different life. Like Fly, he roamed the streets at night looking for customers. “You can work as a taxi driver and accentuate the fiction-like existence. I tried to do that. Maybe that’s why I was so distracted,” he tells me.

But mostly he hated it. Besides not being a night person and lacking a sense of direction, he needed glasses for an eye condition that prevented him from seeing clearly at night; a fact he was unaware of at the time. “I thought the city was foggy,” he says, laughing. That detail, along with many others from those years, is not in the book. He would have preferred not to use the premise of a taxi at all – afraid the book might be pigeonholed as Taxi Stories. And yet the transience that comes with the profession – the aesthetics that Hage was looking for – and the automatic access to a wealth of characters was too good to pass up. “I was tempted. I failed,” he says.

He needn’t be worried about the book being shrugged off as a thinly veiled memoir of his cab-driving years. Carnival is too good for that, too imaginative, too original in its ways

of dealing with violence and loss. There is no sensationalism here. It is a pageturner, but a pageturner for all the right reasons: Hage’s prose is addictive for its rhythm and for the emotional truth rooted at the heart of even the most fanciful sentence.

One of the truths that Hage deals with in Carnival is our necessity to work out the evil impulses that come from historical forces. “It’s permissible as long as it’s contained, whether it’s through sports or beheadings or the torture of animals …” Or a carnival. Hage despises “polite literature,” and in Carnival, he deals with the colliding histories in the North American city in an amazing, original, and impolite way. mRb

0 Comments