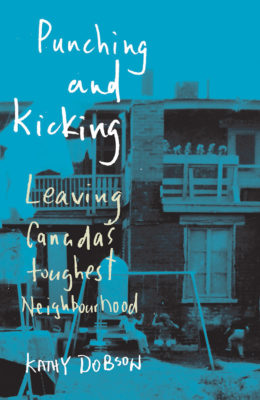

It doesn’t take long for the reader to learn a little something about Kathy Dobson. In the first pages of her memoir Punching and Kicking: Leaving Canada’s Toughest Neighbourhood, she makes it clear that she’s not afraid to hold a grudge, opinionated as all get-out, and so fiercely loyal that if you mess with her family – and she’s one of six sisters – she’ll “fuck with you and yours all day.” In this book, the sequel to 2011’s With a Closed Fist: Growing Up in Canada’s Toughest Neighbourhood, Dobson weaves a rollicking tale that’s as tough as the neighbourhood she hails from.

Montreal’s Pointe-Saint-Charles neighbourhood was a different Pointe back in the 1970s, long before its more recent gentrified iteration, when it was one of the country’s poorest areas. The book takes place during this era, following Dobson, her family, and the wider community in the Pointe as she moves from high school to college.

The “leaving” mentioned in the title is more complicated than pure geography. This is not a story that ends with some tremendous rags-to-riches triumph, where the main character successfully punches and kicks her way out. No. It’s a coming- of-age memoir that reads much more like a novel and provides insight into the process of growing up in poverty. Leaving is a continuous concept that requires consistent punching and kicking. Dobson’s work is engaging – it is indeed a page-turner – but it challenges any simple narratives one might have about what it means to be poor.

Punching and Kicking

Leaving Canada’s Toughest Neighbourhood

Kathy Dobson

Véhicule Press

$24.95

paper

240pp

9781550655070

“People will say to me, ‘How did you get out of poverty?’ They really think there is a road map,” she explains. “But you have to ask about why we have people who are so hardworking, [and] don’t want to be poor. Why are they still poor? Why do we allow people to stay poor in Canada? That’s the question. Not how did one person get out.” And even though Punching and Kicking is about Dobson, she never disconnects herself from any of the other people she has described throughout the narrative. Her story demonstrates the need to consider the people of the Pointe as funny, caring, resourceful, and smart, as well as angry, fallible, and imperfect, as a matter of course.

Because, for Dobson, it’s important that this is absolutely not a book about romanticizing the poor. “I’m embarrassed and of course ashamed of things I said or thought or did at that time,” she says. “The public is going to think I’m terrible, look how racist I am being, or insensitive, or even just politically incorrect. We want to like the poor people or we don’t care. It is this idea of making people uncomfortable on purpose, which I admit to. They should feel uncomfortable.” Dobson’s commitment to telling it like it is means that sometimes the book can be a bit jarring to read.

Part of this comes from Dobson’s narrative voice, which never wavers. Always unflinching and honest, often dealing in uncomfortable topics, speaking from

the perspective of a young girl and then a young woman, moving from high school to college. The narrative is told in a way that doesn’t hold back – at one point self-consciously discussing how Dobson’s epileptic sister is upset about Margaret Atwood’s use of the term “throwing fits,” but then Dobson also makes use of some questionable language herself. Yes, it’s hard to read the depictions of disability in the book, but the metafictional irony is one of Dobson’s tactics. “It’s got to be honest,” she insists. Poverty is not just about people having less money, it is a system that prevents whole communities of people – from all levels of the socio-economic strata – from pushing against assumptions they might have.

Her vibrant descriptions of college classes will make any teacher feel pretty darned good about the relevance of their profession. But at the same time that Dobson presents the many ways that education provided her with opportunities to engage with her own preconceptions and challenge beliefs, she also makes it clear just how close-minded middle- and upper-class folk can be. The introduction of her more upwardly mobile boyfriend Jack, a McGill student, provides a means of presenting this disconnect: whereas Dobson discloses her own ignorance in stark relief, Jack is initially depicted as the clever one. But chapter after chapter, Jack reveals himself as unaware and unwilling to understand anyone else’s perspectives.

Whereas Dobson’s approach to education began with an initial realization that “people do things that don’t make sense. But if you see it from their perspective,” she explains, “culturally, socially, economically, or whatever, suddenly things make sense. And that was something that was amazing to me. Suddenly I understand that there were so many things I didn’t understand.” But Jack is not willing to think outside of himself – he consistently assumes he knows what is best. Not only is he an insufferable and offensive pedant, he refuses to accept Dobson’s family or even responsibility for his part in an unwanted pregnancy.

Dobson’s confessional story of abortion is yet another instance where she underlines how poverty affects so much: “What does it do to you to live with the constant fear of the things that go along with dire poverty? If you’re in a situation where you’re being sexually abused and you have no way of escaping it? Or you need an abortion? All of those experiences are completely different for someone living in poverty than [for] a middle-class person.”

When Dobson says these words, it is as if she pinpoints exactly what is wrong with folks like Jack: “We think we know what people need and we’re not even thinking that we think we know what they need. We’re assuming they’re on the same page. We are not even deliberately being condescending. We honestly think this is what they need and we just have to give it to them and make sure they get it. Never thinking maybe that, no, actually that isn’t what they need, that isn’t what they want. I mean, maybe we should ask them?” Dobson, through her generous, courageous, emotional, and just as amusing as moving recollections of her own life, asks this question, and provides readers with an answer. There’s as much a need to see people with less money as people – to listen. Dobson’s book offers readers this opportunity. mRb

0 Comments