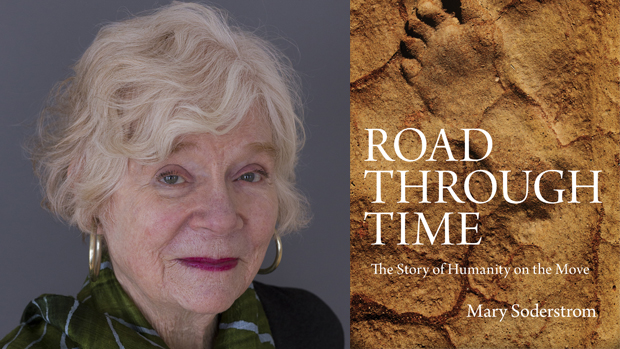

Mary Soderstrom might just be my new favourite writer. She’s been writing for years, and we’ve been reading her for years, but meeting her reveals an energy that is contagious, and a humility that should be. Soderstrom in person is as unassuming, open, and delightful as she is erudite and elegant on the page.

Perhaps there is a kind of quiet that comes from looking back on a life well written – even as the writing continues, fuller steam ahead than ever. Soderstrom is so focused on where she is going that she seems happy to blur the details of where she has been. “Is that in the book?” she asks as she relates an anecdote that might have been pertinent. “Did I put that in the book?” The book in question, her fifteenth, has been on shelves a little over a month, and already the author has moved on. Already, in fact, she is two books down the road.

This juncture could lead to a smooth segue about the figurative weight of Road Through Time: The Story of Humanity on the Move, but Soderstrom’s latest non-fiction offering contains very little of the author. Personal road trip stories from Soderstrom’s youth and from more recent travels are used as bookends, providing a sense of awe, but Road Through Time, while steeped in her fascinations, is no confessional journey. “I don’t like having lots of stuff written in the first person,” she says. “I think that’s egoistic, and I get annoyed.” Soderstrom has a strong literary voice – the prose is cut through with the ebb and flow of her trademark loveliness, as she gestures at, for instance, “the eons-long waltz of continents over the earth’s surface” – but she is not her own character in these pages.

Road Through Time

The Story of Humanity on the Move

Mary Soderstrom

University of Regina Press

$26.95

paper

256pp

9780889774773

Time accordions in and out in the book, from incomprehensibly deep time to more accelerated, compact contemporary movement. Soderstrom relates the history of roads from humans’ exit from Africa across the Red Sea, examines the shift away from nomadism, and looks at trade, marine, and martial routes. Our ancestors’ exploitative instincts are followed to modern times, with chapters on urbanization and industrialization, the ascendancy of the automobile, and international perspectives. Every chapter is thick with irresistible detail, from the history of Roman aqueducts in Portugal to land-division protocols in nineteenth-century America. The meticulous endnotes marry facts and source information with the sort of inherent poetry that so captivates writers (referencing an International Space Station video of the Red Sea, Soderstrom notes that “the clouds at the end obscure the opening of the sea at Bab al-Mandab, called the Gate of Grief because of its tricky, strong currents”).

Throughout, Soderstrom draws attention to the impact of the human presence, what she refers to in the book as “dirt packed down by people.” “The basic thing,” she tells me, “is that we – anatomically modern humans – took over the world.” With Homo sapiens comes, inevitably, destruction – climate change, water crises caused by deforestation. Soderstrom’s environmentalism is matter-of-fact: the road, she says, will take us to the end of days, yet we walk on. “If you think that there’s really no hope at all, then you’re paralyzed.”

One glimpse of hope among the shadows is the resilience of women. Discussing the migrations of early humans across the planet, Soderstrom writes, “bring your women and the stage is set for permanent, game-changing settlement.” Settlers lived longer and got healthier, resulting in “more help for young families from grandmothers and older aunts.” The so-called Grandmother Effect also allowed women of child-bearing age to have more babies closer together, increasing the collective survival rate. “One keeps having children,” Soderstrom says now, even in an uncertain age, which is itself “an act of hope.” Feminism seeps into Road Through Time in more subtle ways as well – a discussion of the genetic path of the “Eves” from whom all modern humans are descended, or a recollection of Soderstrom’s mother’s vigil over her young daughters as their Greyhound plowed through the northern-California night.

In a feminist light, too, Soderstrom is generous, sympathizing with young parents’ creative dry spells. “When my kids were small,” she says, “I didn’t do very much writing. I tell people that actually I’m ten years younger than I really am! Between my first novel in 1976 and the second one, there’s almost twenty years.” Even in those seemingly unproductive years, however, she says, “you’re absorbing all kinds of ideas and experiences.” Material for perpetual storage and possible use, along with heaps of clippings and notes.

She still goes back, for instance, to notes from a 2001 trip to Africa when she was writing the novel Violets of Usambara. There has always been a great deal of cross-pollination in Soderstrom’s work, with characters or even entire scenes sneaking from one book into another. “It seems synergistic to me,” she says, unconcerned; “things are interwoven.”

Now far from her fallow moments, Soderstrom always has both fiction and non-fiction projects on the go. Her next book, due out next year, is a geopolitical comparison that twins various states. And she is currently in the early stages of research about concrete, an outgrowth of the urban preoccupations that arose in writing Road Through Time. She is gleeful about her preliminary findings – the existence of a brotherhood of engineers founded in the wake of bridge-building tragedies, Bauhaus design influences, a long-forgotten scene in Faulkner. “Actually, concrete is terrific!”

That thematic seeding between books creates a sense of continuity, and speaks to a learned and curious mind. “For a long time, my default password was ‘curious,’” Soderstrom confides – unsurprisingly, given her tirelessness, and the breadth of her involvement and career. What will she do when she retires, I ask, as if writers ever retire. “Play the piano!” she laughs, before tossing off the most succinct description of writerly activity I’ve ever heard: “I’ve always said that I work never and always.”

“The roads we build determine our future,” Soderstrom reminds us in Road Through Time. As for what that future will look like for humanity… “I’d hoped to have a more definite end to the book, that I could tell people what they ought to do, but I don’t know what they ought to do. It’s just bearing witness to some extent. We don’t know where we’re going. It’s impossible to think of us going on forever. The question is how do we go out.” And what we leave behind. In Soderstrom’s case, that legacy is well lined, and still pushing forward. mRb

0 Comments