“Like most trans women I know, I have a great deal of anger and grief that I’m perpetually trying to manage and reconcile,” jia qing wilson-yang admits while we discuss her debut novel, Small Beauty. “I wanted to offer a discussion about the way anger and grief affect trans women and hopefully offer some empathy and ways to move through it. Both for myself and potential readers. At some points in the story I felt like I was creating something that I needed to hear.”

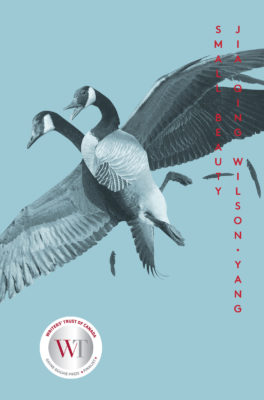

Small Beauty follows the story of Xiao Mei, a young mixed race Chinese trans woman coming to terms with the loss of her cousin, Sandy. Abandoning the city – along with its labyrinthine welfare system and the complicated community of trans women she’s fought hard to become part of – Mei runs back to the small town where she and Sandy grew up in order to try to work out her feelings. Holed up in the now empty house three generations of her family once inhabited, Mei’s story begins to unravel, moving hazily back and forth through time, exhuming the histories of queer ancestors, violence, grief, and love that brought her to the present. Wilson-yang deftly deploys recurrent motifs throughout the text – including the somewhat ominous portent of Canada geese – to sew the novel’s non-linear structure together.

Small Beauty

jia qing wilson-yang

Metonymy Press

$16.95

paper

176pp

9780994047120

That both real and perceived whiteness and straightness, wilson-yang says, extends even to the entry points of queerness within rural spaces that many queer and trans people of colour first encounter. “I have been pleasantly surprised at the little ways that rural spaces are much queerer than we may expect,” wilson-yang says, “but have also been put off by the whiteness of that queerness. When I think about Chinese people in Canada, I know that there are so often Chinese folks in small towns – we are there. And for sure some of us are queers.”

These ideas materialize within the plot of Small Beauty through chance encounters that unearth hidden queer histories in Herbertsville. Shopping at the grocery store, Mei is confronted by Diane, a “woodsy dyke” she comes to learn was her late, seemingly straight aunt Bernadette’s on-again, off-again lover of many years. The revelation of her ancestor’s secret queer life, and the later discovery of a cache of photos of trans women from decades past concealed within the lining of an old suitcase, throw Mei’s entire perception of her life and history off balance. The photographs Mei discovers bring to mind the real-life discovery of photos documenting the previously unknown Casa Susanna – a secret resort for presumably middle-class cross-dressers that operated during the 1950s and 1960s in the Catskills, New York.

“Unearthing those histories is tremendously important. They are histories that are intentionally buried. The result of that burying is that those of us left in the present day have to find examples that we are not an isolated incident of human weirdness. Something that I wanted to show was that for Mei, the histories of the kind of person she is are hidden.” No longer a sole island of Chinese trans weirdness in white straight cisgender Herbertsville, Mei’s discoveries lead her on a path to something like healing.

But still, wilson-yang reminds us, those histories don’t provide a perfect and idyllic reflection for racialized trans women like Mei. Much like the real-life Casa Susanna photographs, both Diane and the women depicted in the pictures Mei finds are white. “These histories are fragmented, compartmentalized. She doesn’t find a stack of photos of queer trans women of colour because part of what made things like Casa Susanna possible was whiteness. For me, and I think for other queer and trans folks of colour my age, who came of age in smaller places, and probably in cities too, entry points into LGBT spaces, queer spaces, trans spaces, were all white. Mei can find recordings of her history in pieces, but an example of something close to the entirety of her being is much more rare.” Only through reaffirming her links to the trans women she left behind in the city will Mei truly be able to feel connected to the land of the living.

Small Beauty is the first novel published by Montreal-based Metonymy Press, and wilson-yang has nothing but praise for the small press. “My experience with Metonymy has been fantastic,” she says. “I came into my relationship with them not knowing a thing about publishing and the more I speak with other writers the more I am impressed with the ways that they have involved me in the process of producing a book. And they are connected to and a part of the communities I was connected to and a part of when I was in Montreal. I knew Ashley [Fortier, one half of Metonymy’s publishing team] years ago when we were both in Guelph. There is a sense of shared history that I love about working with Metonymy.” Though their stated mission is to “reduce barriers to publishing for authors whose perspectives are underrepresented,” with the publication of both wilson-yang’s Small Beauty and Kai Cheng Thom’s upcoming Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, Metonymy are quickly becoming the premiere publisher of trans fiction in Canada.

Wilson-yang’s novel takes its place beside such books as Imogen Binnie’s Nevada (2013) and Jamie Berrout’s Otros Valles (2014) in the emergent genre of trans lit. These novels, written by trans authors with trans readers in mind, stand in stark contrast to what writer Casey Plett refers to as the Gender Novel – narratives crafted by cis writers that appropriate some of the trappings of trans experience to make arguments that often have little to do with actual trans people. Well-known examples include Kim Fu’s For Today I Am a Boy (2014), which, like Small Beauty, focuses on a Chinese-Canadian trans person in rural Ontario, but, as Plett describes in her article in The Walrus, idolizes a Christ-like experience of exceptionalism rather than telling “stories about real, struggling people.”

Already awarded an Honour of Distinction from the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Dayne Ogilvie Prize for LGBT Emerging Writers, Small Beauty’s quiet power is well on its way to much-deserved acclaim. The first-time novelist remains humble: “I’m moved by the response this book has received, it’s been a lovely surprise. I’m deeply grateful for the opportunity to write.” mRb

0 Comments