“The short reach of my long arms prevents me from grasping the world”

– The Death of Marlon Brando

Read this book. This may be a strange way to start a review, yet it seems to be the underlying message of every reader that comes across this novella, or, rather, this grade school composition, as the narrator, a boy named Charles, calls it. Indeed, as the translator notes in his introduction, the book “has received relatively little critical attention despite being listed as one of a hundred must-read Quebecois novels,” and despite the fact that well-known journalist and literary critic Gilles Marcotte wrote that it “reminds you of Steinbeck, Yves Thériault.” I say, read this book because it should be a classic, read this book because it is a masterpiece.

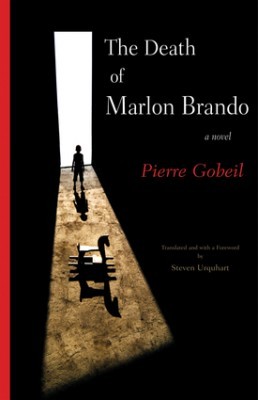

The Death of Marlon Brando

Pierre Gobeil

Translated by Steven Urquhart

Exile Editions

$18.95

paper

152pp

978-1-55096-313-7

Drawing parallels with the multi-faceted Apocalypse Now, The Death of Marlon Brando reveals its complexity of themes like a layered cake. Gobeil uses repetitive and keen descriptions (e.g., the rotting smell of leaves) to depict the changing season from summer to fall and visions of farm landscapes to encapsulate themes of identity, language, and freedom. Steven Urquhart, the book’s translator, is carrect in his assertion that there is a sense of death and rebirth in Charles’ narration. The early fall which Gobeil wishes us to see, smell, and touch is a transforming experience. It refers to a loss of innocence, to a stealthy, manipulative rape in a silent barn under sheets of rain. But the transition of the weather and landscape also speaks of the possibility of renewal, of coming to terms with the experience, as if the book were bi-temporal, written as much for the child who is abused as for the adult who wants to liberate himself from that childhood horror.

The genius of this book is to pack so much into a mere 115 pages. The brilliance of Pierre Gobeil’s double entendre French text is nearly impossible to translate. Urquhart is aware of that and has provided some helpful notes to accompany the English text. Let’s hope that this novel will finally take its rightful place in the pantheon of Québécois literature.

The Death of Marlon Brando will be launched at Blue Metropolis on Sunday, April 28, at 3:00 p.m.

Hello Luca,

Many thanks for this review. I am thrilled to see someone else enjoy this troubling, but incredible novel. I am not sure if Pierre has read this, but I will send it to him. Again, many thanks. I do hope it becomes a classic.

Cheers,

Steve