The title suggests tangled nights on the beach, afternoon cocktails, at least a bit of coming-of-age necking. But That Summer in Provincetown is only glancingly about any such summer. The titular season, on the still-carefree eve of the AIDS epidemic, is covered in a six-page erotic body count, serving only to precipitate the premature, hollow-bodied, disgraced death of Daniel, cousin to the narrator, Mai. From the dying man’s bedside, the novel skips back across his extended family, tracing their relocation within their native Vietnam, their immigration to North America, and particularly their trysts and transgressions.

Structure dominates storytelling in this novel: each chapter opens on Daniel’s death, and goes on to revisit family history through the frame of one character – Horny Uncle Hai, Daniel’s Parisian mother, Mai’s own mother and her assorted paramours. The world of That Summer in Provincetown is utterly matriarchal – the grandmother looms everywhere, and the mother, fallen and redeemed, is the most vivid figure in the novel. The men, meanwhile, are uni-adjectival – handsome, charming, Arbitrary Luck careless – with the exception of brother Tim, who is portrayed in a plausible, intimate light. Every writer has favourites among their characters, but unjustified transparent allegiances can skew the reading. Mai, the narrator, is not deliberately unreliable, yet the resulting attention is scattered, diffuse. We don’t know where to look, and we never quite trust the author to tell us.

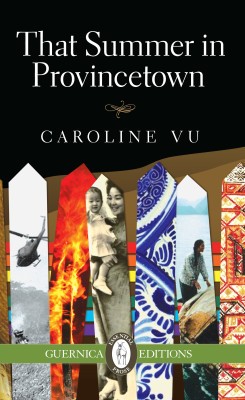

That Summer in Provincetown

Caroline Vu

Guernica Editions

$20.00

paper

134pp

9781771830355

The novel is saved by occasional flashes of expressive flair: Tim, the baby, is described as “a pebble that you kick out of your way. The only time you notice its shape is when it leaves a dirt mark on your new shoes.” Elsewhere, we read: “With its ebb and flow, the war occasionally lulled to sleep.” The author is notably perspicacious when it comes to death: “When fathers of classmates died,” Mai confesses, “I didn’t feel bad. I felt jealous instead.” Many of the choices we make – notably migration – are impelled by mere survival, and their outcomes decided by fickle luck. Yet at the heart of That Summer in Provincetown is a stirring insolence against death – bring it on, they seem to say. Whether through a fling, a spur-of-the-moment adoption, or a summer of ill-fated love, Vu’s characters share a reckless appetite: life wins.

Vu’s structure is interesting, and subtly introduced. By the time we notice that Daniel’s death is the chorus, we are so deep in the exuberantly flawed escapades of his living kin that mortality is a slow, cold shiver. But That Summer in Provincetown feels rushed, in need of a more convincing edit. Some family members come out of left field, and might have stayed there without adverse effect; likewise, some anecdotes (such as a memorable, lengthy aside on irritable bowel syndrome) might have been omitted. The book’s uneven registers, grammatical mishaps, and most of all its exposition hobble the instincts that earned Vu a Quebec Writers’ Federation First Book Prize nomination for her first novel. Her second, which should have shown off an emerging author honing her storytelling chops, is instead a cobbled-together recounting. mRb

0 Comments