Politics and families don’t often mix. When it comes to electoral politics, we can easily find ourselves irreconcilably flailing towards one another from our respective ideological quadrants. I’ve been at odds with relatives over our partisan leanings my whole life. It’s the kind of dissonance that makes me uneasy because the chasm isn’t really that significant: they’re pro-choice, interested in carceral reform, and increasingly versed in climate justice, to name a few overlaps with my own politics.

However, here lies the main divide: some Canadians still think it’s possible to believe the two main parties and the veneer they smear onto policies that are meant to maintain the colonial framework to the benefit of the wealthiest, whereas others are eager to see that façade exposed to reveal who’s actually being served by the flavour of democracy in power. The successive iterations of Liberal and Conservative governments that have been shaping and constraining our country’s polity for generations would rightly make many of us cynical, giving credence to Marx’s belief that “the oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class are to represent and repress them.”

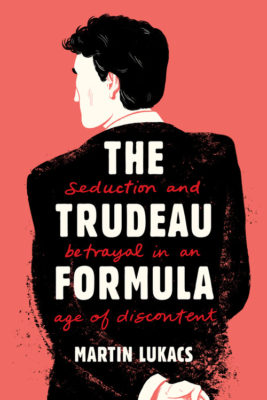

In Martin Lukacs’s The Trudeau Formula: Seduction and Betrayal in an Age of Discontent, the political and rhetorical interchangeability between the country’s two largest parties is shown to have never been as apparent as with the rise of the Trudeau brand over the past fifty years. This thoroughly researched work of investigative journalism, the style of which, when asked in an interview over email, Lukacs credits to a “tradition of muck-racking, activist journalism in Canada” à la Linda McQuaig, Maude Barlow, Bruce Campbell, and Murray Dobbin, paints a picture of a golden boy who was elected on a promise of change while delivering the status quo, drawing parallels between Pierre Elliot Trudeau and his son Justin, the heir to his popularity, reputation, and influence. “A Trudeau victory would represent an anti-establishment breakthrough, while simultaneously signaling to the elite that their interests were to be safeguarded,” writes Lukacs early on, and he spends the remaining few hundred pages dissecting the most glaring such sleights and obfuscations.

When Trudeau came to power, I found that one of my journalistic beats seemed to be trying to spoil the global love-in,” the author revealed in our exchange. “[The book] is a study of how Trudeau has ably served a Canadian establishment that has rigged our economy and political system to serve their narrow interests and stunt our political imagination.”

The Trudeau Formula

Seduction and Betrayal in an Age of Discontent

Martin Lukacs

Black Rose Books

$22.95

paper

304pp

9781551647487

Of course, you’ll say, that’s how it’s always been. But that wasn’t in the Sunny Ways playbook, Trudeau’s brand of positive politics. “The progressive majority in Canada who [Lukacs thinks] are the true electorally silenced majority” is who is shown to be left out of the big-ticket dinner circuit and gravy train served by a backroom script written by a party brass eager for majority rule. And that majority is the book’s intended lectorate. Lukacs is the anonymous fly on the wall of political conventions, arms trade shows, and fundraising dinners, always happening to engage in an exchange that will reveal whose interests are really being served by the stack of policies taken to task. This intimate access and intrigue reads at times like the omniscient narration of a tepid political thriller. Lukacs takes these issues to heart and reveals their instrumentalization by those concerned with wealth production and the safeguarding of our fossil fuel addiction. In so doing, he elevates what is generally relegated to the back pages of mainstream media or ignored completely to a crisis of national interest. In some cases, as with his work revealing who really profits from the sale of Canadian-made large armoured vehicles responsible for the death of innocent Yemeni, the interest is global.

Questions of transparency, honesty, and accountability are the book’s most elemental concerns. They are also at the core of the continuity that Lukacs traces between the past and present. He works consistently to provide examples of how Trudeau’s government is merely a new arrangement of tried tunes of “co-opting the language of Indigenous rights or feminism or anti-racism, absorbing some of the leadership of these movements, making small, selective often symbolic concessions, and ultimately trying to demobilize the power of truly transformative change.”

From the very first pages, readers are offered reasons to become engaged with what the author details as legitimate motives for national outrage: economic inequality, particularly in Indigenous, refugee, transgender, and POC communities; climate injustice; botched electoral reform; corporate greed; offshore tax havens from Trudeau père through Mulroney until the present. “Squeezed by the end of the month, haunted by the end of the world: these are the signature marks of the anxiety and anger of a new Canadian generation,” laments Lukacs. “Justin Trudeau’s Liberals remind us that you can’t always achieve everything you want in government” after one term in office, let alone set a tone for how the outcome of Trudeau’s policies will be any different from prior government agendas. On the other hand, “to win the country we deserve,” writes the author, “we’ll need to stop believing in their fables.” <

One of the strengths of the book is that even though Lukacs’s goal is to accurately disclose the fables of the Liberal government under Trudeau, the writing remains respectful, if at times caustic. “Feigning to the left during elections […] was a Liberal move so much a part of their tradition that it was worthy of a Canadian Heritage Minute,” he writes cheekily of the 2015 election strategy. It fits with Lukacs’s strategy of trying to reach a majority of Canadians who, according to polls, “have values and political opinions — belief in higher taxation on the wealthy, protection of the environment, anti-militarism — that place them to the left of all the major parties.” There’s no need for him to dig deep for controversial fodder about which to flex his wit; Justin has made his own bed where that’s concerned.

Take the well-documented case study of his participation in what Lukacs calls the “Reconciliation Industry.” Gaining sympathy with Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians alike for his early adoption of the “moral feeling” of reconciliation and benefiting electorally from the acts of friendship he has been granted with tribes and councils, his stance changed after a few years in office. As Lukacs writes about Trudeau’s treatment of Secwepemc writer and activist Arthur Manuel, “a pique of conscience isn’t a sign of a policy shift.” Indigenous land protectors are still being prosecuted by the state for standing up for their treaty rights, dismally reflected in the fact that “both [Harper’s] and Trudeau’s governments have spent more money in the courts fighting Indigenous peoples than fighting tax frauds.” Reconciliation is bad for the extractivist economy as we know it, and Trudeau’s government is only interested in it insofar as it benefits the colonial status quo. “Reconciliation wasn’t the unfinished business of confederation. It was the unfinished business of colonization.”

One of the co-authors of the Leap Manifesto, Lukacs tries his hardest to infuse the book with that ambitious if sprawling message throughout, even reserving the last chapter as a coda of realistic hope. Hope in seeing beyond the two-party system that frames the either/or Lib/Con power balance around election time as a “right-wing threat.” As he shares towards the end of our exchange, “the only thing that can defeat the rise of this ugly right is the left. We must offer a more compelling vision that can improve the lives of millions, while combatting racism and taking on vested interests.” So read up and take some of these arguments to your next family dinner. You may end up finding some hopeful common ground. mRb

0 Comments