“‘Twas the late seventies and snowing hard. Already you could feel the bottomlessness of the eighties.” Heroine, Gail Scott’s classic feminist Montreal novel, balances on the border of these two eras. Gail, our narrator, soaks in the bath in a rented room in 1980, recalling her recent experiences as a young would-be militant during the heady days of separatist revolutionary fervour. As she remembers, she also reconfigures what happened, visiting and revisiting her relationships, her moods, and her own trajectory as both an observer and an actor in a time of personal and political upheaval.

Originally published in 1987, Heroine reads uncannily like a book written more recently. It’s a novel about writing a novel – a novel in the midst of writing itself. There is a pervading sense of now-ness to it. Gail, in her bath, is in the process of writing her own heroine into existence – a stand-in for herself, raw but also curated.

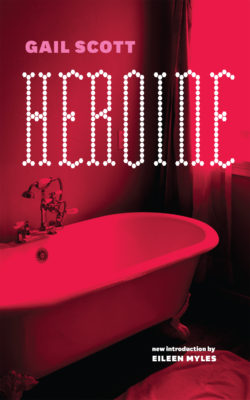

Heroine

Gail Scott

Coach House Books

$19.95

paper

192pp

9781552453919

“Putting one word ahead of another on the page gives a feeling of moving forward. I started thinking of the novel I would do,” Gail tells us. A novel is a thing to be done, an action, rather than the mere documentation of past actions through writing. As the water grows cold, she cycles through different versions of scenes from her life. Even in her memories, she is intent on recreating herself. To her “shrink,” she says, “The point is we have to create new images of ourselves even if at first they’re superficial, in order to move forward.”

One of Gail’s preoccupations is that of love, and whether or not romantic relationships can uphold the revolutionary values of the left. “The couple is […] back in the form of the new woman and the new man,” we are told. But who are these new women and men? Gail recalls her struggle to maintain the uncertain affections of a polyamorous male lover. She is also possibly becoming open to falling in love with women. But she’s not there yet. First, she has to get past this man, his evasions and avoidant tendencies. Slowly, Gail realizes that the men she sleeps with and organizes politically with are largely dismissive of gender equality. Thanks to the women around her, including Marie, a compelling and confident filmmaker, Gail discovers the concepts of patriarchy, gender oppression, and feminism.

Heroine is not a lesbian coming-of-age novel, not quite. It’s more concerned with a sort of queer shift that can happen alongside heterosexual desire. Gail becomes increasingly open to the influence of other women, and to their attractiveness. She starts off seeing them as rivals for male attention, but over the course of the novel, her jealousy morphs into admiration, respect, even desire. Marie, somewhere between a friend and a lover to Gail, is an emboldening presence in her life. She is intent on “experimenting in new ways of expressing women’s voices.” This approach influences Gail and her own writing. “When I write I talk out loud,” Marie tells her.

“J’ai décidé de m’écouter moi-même.” As Gail learns to listen to herself, her novel emerges, flawed yet deeply engaging. “Even a revolutionary isn’t perfect,” our heroine reminds us. “Of course she has to try.” mRb

0 Comments