There are some books that deserve to be read in one sitting. When read uninterrupted, their narrative power quietly but forcefully steals over you as you flip the pages faster and faster.

Lise Dion’s The Secret of the Blue Trunk is one of those books. First published in 2011 as Le secret du coffre bleu and now available in an English translation by Liedewij Hawke, it tells the true story of how Dion’s mother, a young nun from Quebec, ended up in a German concentration camp during the Second World War. Rather than straining to impress with literary prowess, it makes a frank appeal to readers on an emotional level.

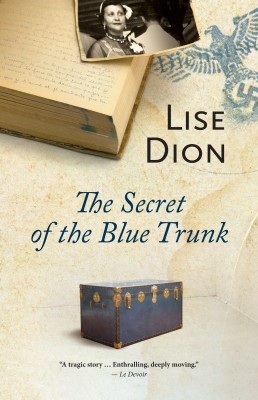

Growing up, Dion knew she was adopted, but her adoptive mother’s past was in many ways a mystery toher. When her mother died, Dion was finally able to open her “mysterious, unfathomable, untouchable blue trunk,” which had been off limits for Dion’s whole life. She was shocked by what she discovered inside: a photo of her mother in a nun’s habit, a German document from 1940 stating her mother’s arrest, and five notebooks with the title “So that I will always remember.” “Now my mother transformed into a real heroine,” Dion writes. “I knew she had the backbone to come out of the war alive.”

The familiar quest of an adopted child is that of the search for a biological parent. Dion, on the other hand, goes on a search for the truth of her adoptive mother’s past.

The Secret of the Blue Trunk

Lise Dion

Translated by Liedewij Hawke

Dundurn

$21.99

paper

168pp

978-1-45970-451-0

Dion is well known in Quebec as a humorist, but this story is anything but humorous. Yet her talent as a storyteller is evident. The narrative is told in straightforward, mostly unadorned prose, yet there’s also a certain exuberance to the writing style that might have been polished out in a different kind of book. For example, Dion uses the occasional exclamation point, a punctuation mark that is usually reserved for dialogue, but in this case suits the voice of the narrator. What reads as sometimes slightly choppy honesty gives the writing an immediacy that makes it both compelling and convincing.

When Armande leaves Chicoutimi in 1930 to travel overseas and train to become a nun in France, she delights in many new experiences: “I simply couldn’t get over it. We could eat, sitting at a table, while the train travelled along! And, what’s more, while admiring the passing scenery!” The sweet naïveté evident in these scenes makes the later gritty, shocking details of life in the concentration camp all the more heart-wrenching.

Eventually forced to confront what had been happening in the world outside the “comfortable cocoon” of her isolated religious community in 1940, Armande voices the utter senselessness of her experience: “I could die, then, simply because I was a Canadian citizen! That didn’t make sense. My crime was being a British subject. It was all so abstract for me since I had never even set foot in England!” From here, the narrative takes a turn, and the reader is drawn into a very dark world.

A slight reprieve comes in the form of an unlikely bond that develops into a love interest, a lifeline for a despairing reader. The other bright spot in an otherwise dark narrative is the celebration of the bonds of female friendship; most likely what kept Armande alive.

Although it doesn’t necessarily have any new information to add to the glut of literature surrounding the war, Dion’s reconstructed narrative offers a new (and specifically Quebecois) voice, one that is refreshingly direct and compulsively readable. mRb

0 Comments