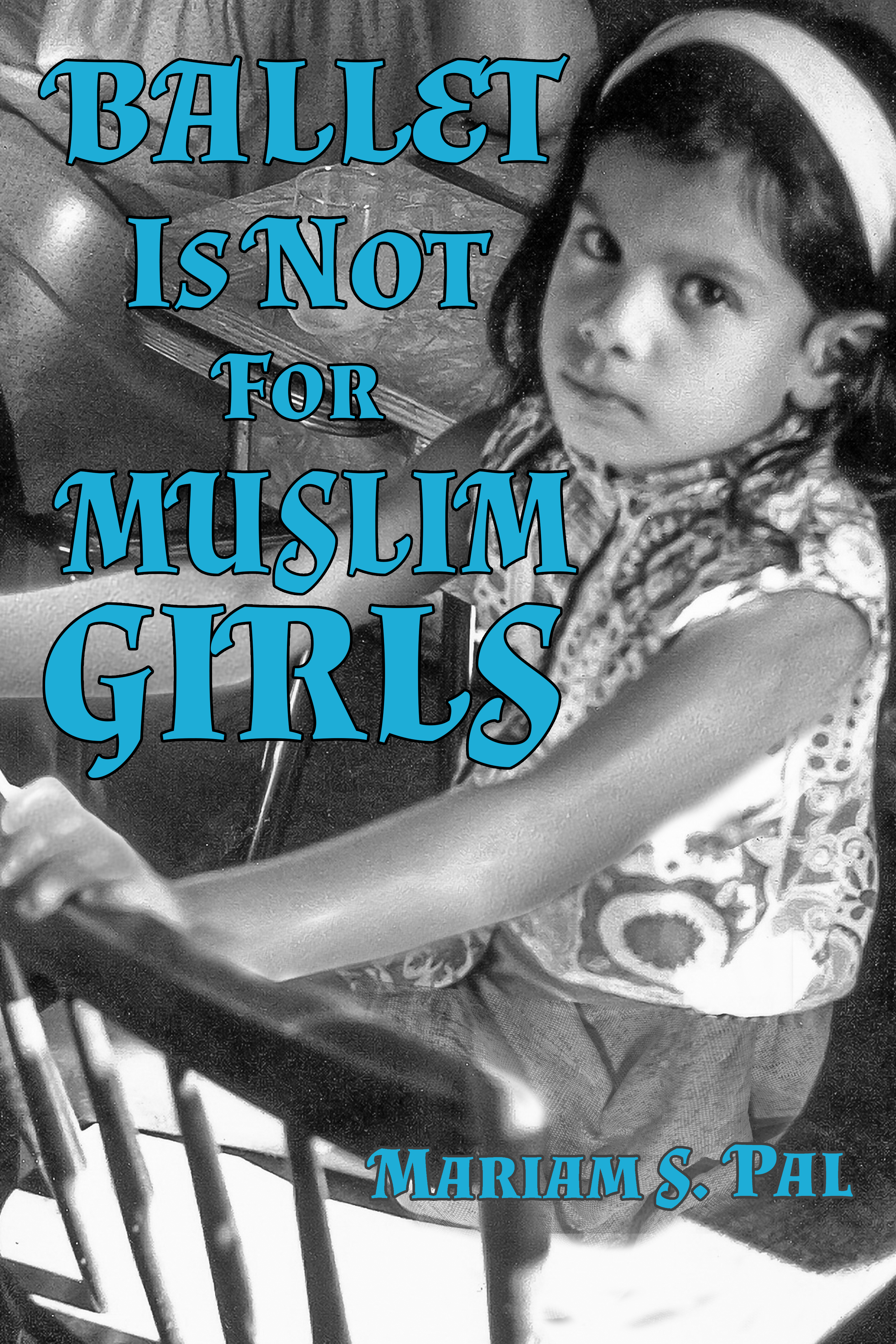

Early in Ballet is Not for Muslim Girls, readers encounter a young Mariam Pal, who writes to her grandfather in Pakistan, inquiring about her interest in ballet. He writes back to her, “Your Papa is a Muslim and Islam does not encourage ballet for girls.” This letter, placed in the first few pages of the book, introduces readers to the overarching thread explored in the rest of the text – Pal yearns to understand why, in her life, the word, “Muslim” was so often synonymous to “no.”

In publishing, Ballet is Not for Muslim Girls, Renaissance Press has committed to its mandate: Diverse Canadian Voices. Pal’s book serves as an overdue account of what it truly means to grow up within the nuances of multiculturalism. Experiences like Pal’s have long since existed, even if not at the forefront of stories in popular culture.

Ballet is not for Muslim Girls Renaissance Press

Mariam Pal

$20.00

Paper

304 pp

9781990086205

For this reader in particular, a Canadian born from two Muslim parents, the book is littered with relatable experiences. I visited Bangladesh as a young woman, just as Mariam visited Pakistan. I, too, resented the constant stares from locals, and I was also told it was a result of my Western clothing. And when, like Mariam, I adopted the salwars and normalized clothing belonging to the culture I was in, I was still met with stares, and I was as disheartened to learn it was because I was a woman who carried her chin up and looked straight ahead when walking – something only an outsider woman would do. I, too, kept a diary from that trip, in which I share similar accounts of feeling overwhelmed with love for my native country, and simultaneous disdain for what I perceived to be a “backwards” way of living.

True to its title, the book offers more insight into Pal’s Muslim and Pakistani influence from her father’s side, and less of her mother’s influence as a Polish-Canadian woman. Pal acknowledges this as a result of early loss: her mother died when Pal was a young woman. But what she recalls of her mother, and what she shares in the book, ultimately amounts to an admirable force. Pal portrays her mother as a young woman who fell in love with British culture, who saw no reason not to celebrate the love she developed for a man of colour, and who, in the final years of her life, would satisfy her long pursuit of a higher education. Despite the personal tragedy, Mariam’s persistent questioning and curiosity seem ultimately inherited from her maternal side.

Pal’s life proves to be one of both resistance and concessions, and her inquisitive nature persists throughout her entire life. If, when family from Pakistan came to visit, the alcohol needed to be hidden away, then what to make of her father’s affinity for a nightly martini? At the same time, he adamantly refused pork in the name of Islam. In turn, Pal becomes partial to turkey bacon, a substitute her father will continue to deny, but which satisfies Mariam’s own predilections.

Growing up biracial, Pal faces a chasm while navigating her relationship to her father. But – yet again, relatably – it is not for lack of love. Though her parents misplace their own insecurities onto her at times, their love for her is undeniable.

Towards the end of the book, Pal’s cultural contradictions culminate to the apex reached by most Desi girls: marriage. Her father, of course, disapproves of any non-Muslims. Why is a Pakistani who married a Polish-Canadian woman so scared of the idea of his daughter potentially doing the same? Pal learns to understand this fear – not of the Other, but of loss of the Self. Papa was able to moderate what he kept and what he left behind of his upbringing, but in turn, this cannot be similarly controlled for his children and grandchildren. In light of this text, my own father, like Pal’s, should know daughters commemorate everything with love, and that there is nothing to fear.mRb

Congratulations to Mariam. I must read this book!

I very much enjoyed reading this memoir, especially since I knew Mariam in high school and our fathers were both professors at UVIC. She was a grade ahead of me and I perceived her as smart, confident and stylish. It was deeply moving for me to read about her internal struggles at the time, and the anguish of being torn in opposite cultural directions. A very well written and poignant account of growing up as a daughter of a mixed race marriage in a very “white bread” society, Victoria in the 1960s and 70s, and how it affected her in later years. I highly recommend this book.

I’ve been meaning to pick this book up for a while now. Mariam lives two doors down from my childhood home. Looking back now I’m not too sure how it all started but I would go over to her house to help with her garden. That relationship grew, and she taught me so many useful skills often forgotten by my generation; keeping a healthy garden riddled with fresh fruits and vegetables, sewing, canning, pickling, and much more. I’ve recently moved across the country to Vancouver Island and I think of her and what she taught me as a child quite often. She’s an incredible woman with so many amazing stories and savoir-vivre. I credit her to my love of nature and plants, as well as my now more developed love for creating things by hand in lieu of buying them. I cannot wait to pick this up.