Sometimes, the most natural way to grieve a loved one is by grieving someone else. In Guyana, Élise Turcotte examines personal and collective grief, guilt, and dreams through the eyes of three Montreal residents: Ana, her son Philippe, and their hairdresser Kimi.

At 139 pages Guyana is slim, and yet its narrative drifts at a slow pace, as one imagines a ghost would. And many ghosts inhabit this mystery novel. The first among them is Kimi, a Guyanese immigrant who, at the beginning of the novel, is found dead, hanging from the ceiling of her hair salon. The police say it is a suicide, but Ana believes Kimi is “a victim of the plague of violence that sometimes ties the living and the dead.” Suspicious, she tries desperately to make sense of Kimi’s death, becoming obsessed with finding Kimi’s motive – or her murderer.

Ana, it turns out, has recently confronted another senseless death: her husband Rudi died of leukemia the year before. A journalist, she has been unable to work since his death, but now she turns her investigative skills to Kimi’s case. Ana finds Kimi’s upbringing in Guyana, a country scarred by the Jonestown massacre, particularly intriguing. The event, during which over 900 people committed mass suicide by drinking Flavor Aid, consumes Ana.

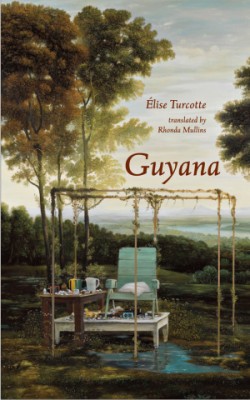

Guyana

Élise Turcotte

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$17.95

paper

144pp

978-1-55245-292-9

Slowly, Turcotte reveals the stomach-turning basis of Ana’s affinity for Kimi and her fascination with the Jonestown massacre. In this book, meanings are opaque, while imagery is exact. Rhonda Mullins’ translation of the novel, which won the Grand Prix du livre de Montréal, was recently shortlisted for a Governor General’s Award. Mullins captures Turcotte’s language beautifully. Descriptions are visual and concrete, while characters’ thoughts are slippery and poetic. (Turcotte is also a poet.)

Violence can be understood in many ways. It is sudden and unexpected; it is systemic and societal; its victim can be a single woman or a whole colonized country. Guyana aims to make sense of it by paralleling the narrative of mourning and the narrative of integration. After all, each immigrant commits a kind of suicide.

There is a fine line between suicide, grief, and murder when we appropriate the dead, as Ana does. Each time it is evoked by the living, a tragedy is brought to life again: “I wanted proof. I wanted to be right. I wanted her to have been murdered. I needed this murder to be completely alive.”

0 Comments