In a city like Montreal, diverse in its inhabitants and stimulating in its cultural offerings, distractions flow in from all around: fast-moving pedestrians and road traffic; the sounds of engines, ringtones, construction crews, music, and chatter; colour splashes from advertisements, store-front displays, and market stalls. But in the midst of all this motion, where can Montrealers find a moment of peace, of grounding, outdoors? By pausing to look at what grows quietly and stoically from the ground, suggests Bronwyn Chester. Lift your eyes and say hello to the motionless, “other” residents of our metropolis – the trees.

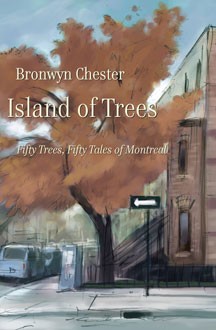

Often, we take trees for granted, seeing them as part of the mosaic that forms the backdrop of our lives. Yet as Chester highlights in her fascinating guide to Montreal’s arboreal life, Island of Trees: Fifty Trees, Fifty Tales of Montreal, these trees should be valued as sacred spots where “the earth resurfaces” as “islands” in the waters of a built environment.

Island of Trees

Fifty Trees, Fifty Tales of Montreal

Bronwyn Chester

Véhicule Press

$18.00

paper

182pp

9781550653298

The profiles vary from the “regular” trees – native trees that are well represented, like the silver maple, crab apple, or yellow birch (Quebec’s provincial tree) – to the exotic, like the ginkgo, and the rare, such as the green ash, shagbark hickory, and willow. She includes humble species, like the Camperdown elm, as well as the extravagant: among them, the dawn redwood, Japanese lilac, and the “true giants in our midst,” the cottonwood poplars. This guide eschews statistical details, favouring instead a lyrical voice that links the tree to the peoples living around it, as with this description of black pine: “Like the buildings of Old Montreal and the great round-bowed ships docked there, the Austrian pine is solid, dense and on the squat side.” Chester is always a character in these profiles, recalling how she comes to first encounter the specimen she’s describing. Yet, interlaced with her personal narrative are details of the language, social history, and economics of the peoples living around, planting, and using these trees. Accompanying each tale are a useful map of an area in which representatives of the tree can be found as well as fine pen-and-ink illustrations by Jean-Luc Trudel and Charles L’Heureux.

Reading through Island of Trees, one begins to appreciate these trees as survivors facing not only the general challenges met by trees – like weather, pests, and diseases – but also threats unique to the urban setting, including road and sidewalk salt, compacted soil, and development. In her meanderings, the author encounters others who value city trees as much as she does. There’s the wood turner who crafts bowls out of branches destined for the chipper, salvaged from the Mount Royal Cemetery. Another citizen collects chokecherries in Little Italy and makes jams that he sells for fundraising efforts. There are the children who climb the generous boughs of the Amur maple, as well as the many homeowners who plant, prune, cherish, and even decorate trees in their own yards.

As a fitting memorial to Chester’s work, a serviceberry sapling was planted on McGill’s grounds in 2012. This book also ensures that her passion is seeded within other residents of Montreal. Editor Bryan Demchinsky has done an admirable job bringing Island of Trees, the last project Chester was working on before her death, to print. The final words are all hers: “It’s only through the pleasure we take in getting acquainted with trees – and the other living entities with which we share our island – that we are going to live differently, better, on our patch of Earth.” mRb

0 Comments