Exhausted after two straight days of editing the English translation of Dr. Bethune’s Children, Xue Yiwei reluctantly agreed to go on a road trip with a friend. The friend picked him up and proceeded to make a series of wrong turns, missing the exit for the highway out of the city. Frustrated, Xue told his friend, “Oh, just turn left here.” They stopped and got out of the car. It was raining, and they were completely lost in the alien neighbourhood of Plateau-Mont-Royal, across town from his home in Côte-des-Neiges. Avenue Henri-Julien, a street he’d never heard of. And then suddenly he found himself facing a mural of his hero, the Canadian doctor who inspired his latest book.

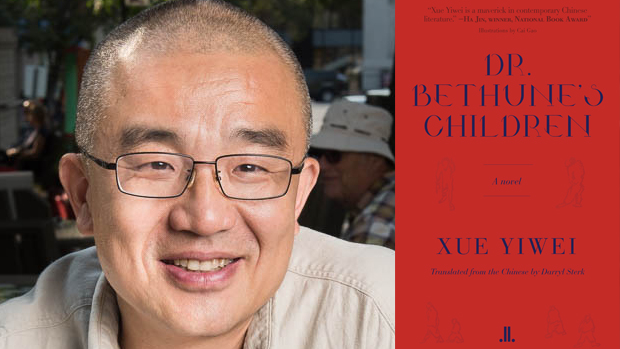

Xue is a celebrated author in China. He has written sixteen books in Chinese and has actually gone back and rewritten ten despite the critical acclaim they received. He is known as much for the meticulous quality of his work as for his prolific output. But he is an invisible man in his adopted city, where he has spent the last fifteen years. His reason for leaving China, he has said, citing Toni Morrison, was “to avoid cliché.” So it seems fitting that this invisible man’s experience of Montreal is so intensely magical.

“I have so many stories like this,” Xue continues. There was the time he was in a café, being interviewed by Caroline Montpetit of Le Devoir. Montpetit began to say that her colleague’s father, Jean Paré, had translated two biographies of Dr. Bethune into French when her expression suddenly changed: Paré himself entered the café. Montpetit recognized the translator, whom she’d never actually met, from pictures she’d seen. She was in complete shock. But Xue happily interpreted what had just happened for her: like the narrator of his latest novel, they were being guided by the spirit of Dr. Bethune.

Dr. Bethune’s Children

Xue Yiwei

Translated by Darryl Sterk

Linda Leith Publishing

$18.95

paper

288pp

9781988130514

When Xue stumbled on another Montreal monument, the memorial for the victims of the École Polytechnique massacre, he was struck by the detail of the year the event took place – 1989. This coincidence was in fact the seed that inspired Xue to write the book, which alludes to but never names the 1989 bloodbath at Tiananmen Square. Xue’s gentle prose is at its most powerful here, and we can assume that this was not lost on the Chinese authorities, as Dr. Bethune’s Children is banned in China.

The book is written in the form of a long letter to Dr. Bethune, who died in 1939 and remains a powerful symbol of idealism for Xue. The letter recounts events in the narrator’s life, as well as in the world. One such pivotal event is the suicide of his schoolmate, a thirteen-year-old boy named Yangyang. It takes place a year before the earth-shaking news of Mao’s death, which prompts Yangyang’s mother to say, “Another boy has died.” Yangyang’s motive for killing himself is twofold: on one hand, he is disillusioned to find that he knows no real, living person as virtuous and devoted as Dr. Bethune. On the other hand, he is a true believer who looks forward to meeting his hero in the next world. Yangyang is one of two characters the book is dedicated to. The other is Yinyin, who is rescued from an earthquake by the Red Army, only to be shot by a soldier years later. But these people are not real, Xue tells me. “And the narrator is not me,” he says. “Actually, I suppose I’m Yangyang.” Because Xue, like Yangyang, like all of China, lost his innocence and idealism around the time of Mao’s death.

The naive belief the Chinese once had in their heroes, their extraordinary revolutionary fervour, is beautifully and succinctly reflected in Xue’s absurdist descriptions: the enthusiasm for a Cultural Revolution in which almost all books were condemned as “poisonous weeds”; conversations that were “forbidden zones,” even between spouses; a time when a person’s worth was measured in their ability to parrot canonical texts. “That retard son of yours!” a mother says to her neighbour, “He can’t even memorize ‘In Memory of Dr. Bethune.’ He’s got some nerve, seducing my daughter like that.”

Xue admits to “gentle irony.” But like his narrator, he remains an idealist. He is not comfortable with the new China and how quickly it has shifted to an opposite national ethos, where material success is all that matters, where trains go so fast, he says, that you can’t see the great Chinese rivers. “China is just … surreal,” Xue says. His narrator goes further, refusing to read the new biography of Chairman Mao, which depicts him as the twentieth century’s cruellest tyrant.

The novel – with its wealth of dualities, connections, and contrasts – is divided into thirty-two short chapters, and even the chapter headings are rich in meaning. Each begins with the indefinite article “A” followed by a noun, for example, “A Lie,” “A Hero,” “A Former Actress” – but there are always two lies, two heroes, two former actresses, and so on, one visible, the other not. This pattern was inspired by Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, about which Xue has written a book. This latter work is itself considered a masterpiece in China. “It’s kind of my vision of the world,” the author says. “There is always something else behind what you can actually see.”

Perhaps, Xue says, Dr. Bethune’s Children could be described as a “transcendental” experience, since he dedicates the book to two fictional characters, and quotes them as often as both Dr. Bethune and Mao Zedong. Or perhaps the right word doesn’t exist in English.

There is this, though, from a short story Xue once wrote called “The True Story of a Family,” a sentence which seems to echo the delight he takes in spotting coincidences: “In my opinion, it was more evidence of life coming from art. That life comes from art is both my idea of art and my idea of life.”

The book is infused with the author’s great sense of delight, making it a pleasure to read. Its honest insights into China’s journey make it essential that we do. mRb

There is a subterranean and enduring vein of Canadian history here…along with the Riel Rebellions, the Patriots in Ontario and Québec and the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, that needs to be explored.